The ultimate prize, pictured ahead of the club where it will be claimed come July.

Getty Images

HOYLAKE, England — In the days following the U.S. Open, there was a particular sense of hope at Royal Liverpool Golf Club, the host for this year’s next and final major championship. How great would it be, a few members and staffers agreed, if Rory McIlroy could end his nearly nine-year major drought, winning once again on their favorite golf course?

That kind of wishful thinking comes natural when a smiling McIlroy graces the cover of this year’s Royal Liverpool Magazine, copies of which sit front and center at the entrance to the club. The belief only strengthened when McIlroy nearly won the U.S. Open at Los Angeles Country Club, some eight time zones west. And if you thought Wyndham Clark was upset about late weekend tee times, ask the folks here in the U.K., who either stayed up until 11 p.m. local to watch the leaders tee off, woke up around 2 a.m. to watch them finish — or mainlined caffeine to somehow do both.

Royal Liverpool — also popularly known as Hoylake, for the town in which it resides — has been waiting just as long as McIlroy for another major moment. The anticipation is cresting, and you can’t blame them. Tom Watson was out playing RLGC on the Wednesday after Wyndham Clark’s win. Catriona Matthew was, too. DP World Tour player and club member Matthew Jordan practiced on the putting green, anxious to qualify for a home Open. A round with any of them would do, but my reintroduction to the course came alongside one of Hoylake’s ultimate authorities, Joe McDonnell.

McDonnell’s been a member for more than 30 years now, which seems impossible because he looks no older than 40, but talks with the knowledge of a club historian. He knows the depth of every green and placement of every bunker. He also knows where all the past greens have been. Where the greens became bunkers. Where the limits of the property have now become mounds, and where past mounds have been softened.

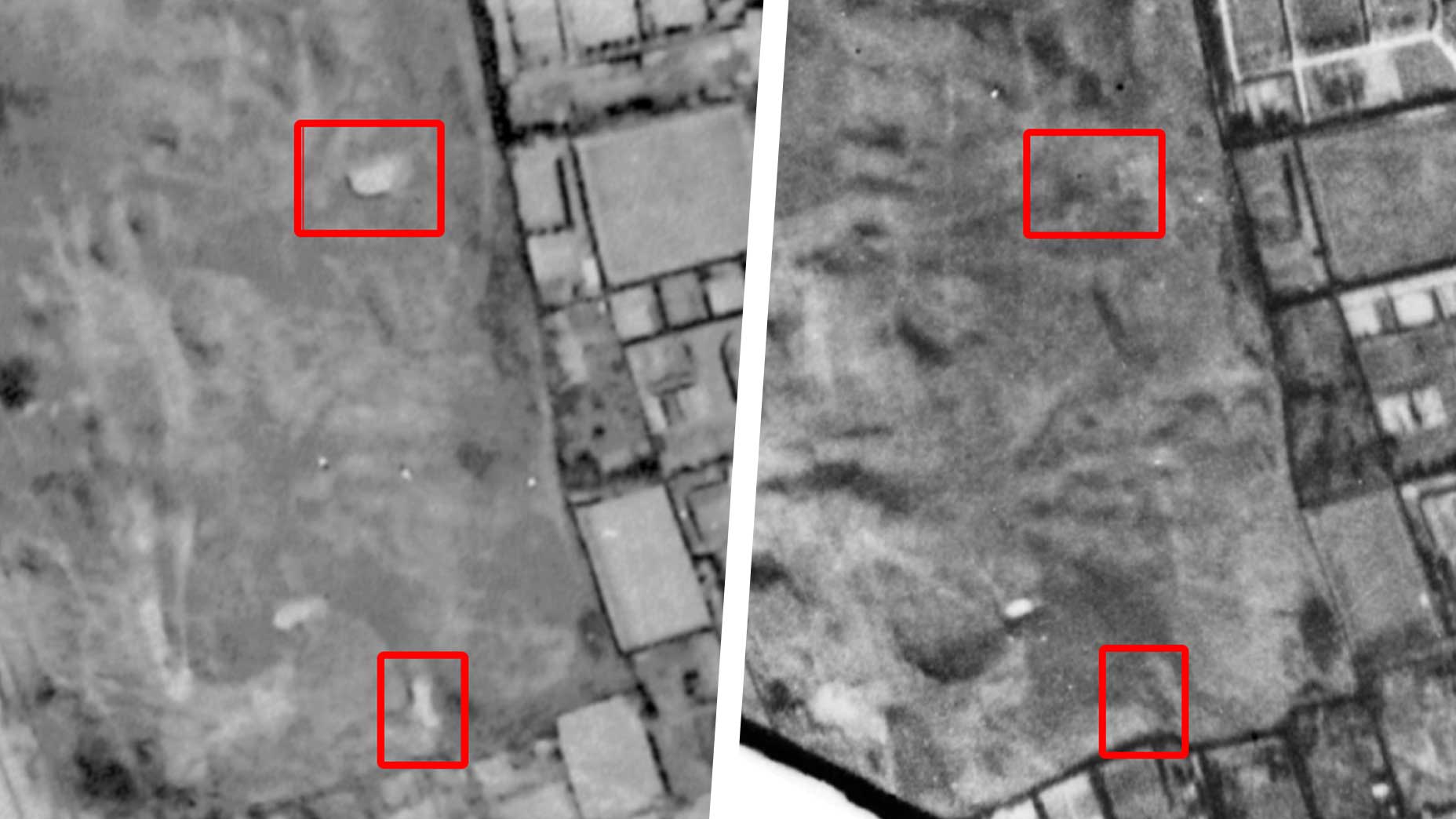

That’s one of the main themes with this year’s Open host. Its history is a tale of constant change — both slight and seismic — surely more than any other course in the Open rota. Seismic turns out to be one of McDonell’s favorite adjectives. But it would feel wrong to ask him to use another word. It’s his job to obsess over these kinds of things. As the head of imagery at the design firm of Clayton, DeVries & Pont, he specializes in 3D imaging, archival visuals, or just making golf holes and their rugged boundaries look like art.

That rigid, internal out of bounds that lines the 3rd and 16th holes? It’s just a mound, but it used to have a moat of sand on its outer ring. The original bunkers, he tells me, were long and connected like that. Then we got obsessed with making the game more difficult and deep pot bunkers with riveted faces became a necessity. You know, putting things in the way of a golfer standing over their ball.

Years ago the center of the property featured an extremely straight, kinda boring par-4, followed by a par-3 that ran north to south. In a spurt of creativity, the club combined the two holes and wove the fairway into a dogleg around gorse bushes to fashion a much more exciting three-shotter. When I successfully two-putted from a swale on the back left corner of the 8th, he informed me I would have needed a wedge from that spot 100 years ago. He then sent along an image that night to confirm it. Bunkers on the far side of greens lost their luster sometime in the middle of the century.

Courtesy

Among the hottest trends in golf is major championship courses getting restored or renovated ahead of their time in the sun. Gil Hanse has become the most popular architect in the industry on the success of many of those projects (see: LACC, Congressional, Southern Hills, Oak Hill, Baltusrol). But there’s something to be said for a club that makes alterations more incrementally than abruptly. It creates something different each time we visit. The Royal Liverpool that Tiger Woods won on in 2006 was quite different than the Royal Liverpool McIlroy won on in 2014.

The size of many bunkers was shrunk after that ’06 Open. Not necessarily to make them more difficult but rather to keep the wind from whipping sand out of them. Some bunkers were even removed while run-off areas were extended to offer a wider variety of short game shot options.

As for this year, plenty has been changed but the biggest shift took place on the 17th hole, a 139-yard snippet of a par-3 that plays in the exact opposite direction as it did in 2014. It brings to mind two obvious questions: 1) Have you ever seen a course flip a golf hole 180 degrees? And 2) Is it a better hole now than it used to be?

The answer to Question 1 (I think?) is no. As for Question 2, it’s hard to say. I’m a sucker for scenery, and the hole now has a trio of islands hanging out behind the green. (If you’d like a look at the old design, you can find it, and plenty of Open bleachers, on Google Maps’ satellite images.) One thing is clear, though: the hole isn’t exactly beloved by the membership. At least not yet. An ultra-penal bunker was added to its original design off the right edge of the green. That’ll test every player in next month’s Open field, but it may be too tricky for the 12-handicapper.

I suppose that makes all this change a bit risky, right? You don’t always get it right. And if the winner magically holes out for birdie as the sun sets over the Irish Sea, the hole may never get touched again.

Thankfully, nothing seems too sacred at Royal Liverpool. From every angle, the plot of mostly flat terrain — at least by American golf course standards — feels like a sandbox. It’s hemmed in by a neighborhood of nice homes on three sides and a seaside nature reserve on the other. Everything in between is malleable.

McDonnell himself even has two holes in mind that he would eliminate yesterday if he was in charge. Wipe them clean off the record. Of course, he’d have to find space for two others somewhere else on the property. But that’s what gets his mind racing, in part because at RLGC that much change actually seems plausible.