In the years since Woods’ first Masters wins, changes to Augusta National have grown more frequent

Getty Images

In the spring of 1959, on the 25th anniversary of the Masters, a guest contributor to Sports Illustrated put the following words to print: “It was one of our guiding principles in building the Augusta National that even our par-5s should be reachable by two excellent shots,” Bobby Jones wrote.

What Jones and his co-designer, Alister MacKenzie, could not have imagined is that those two shots would someday be pulled off with a driver and a wedge.

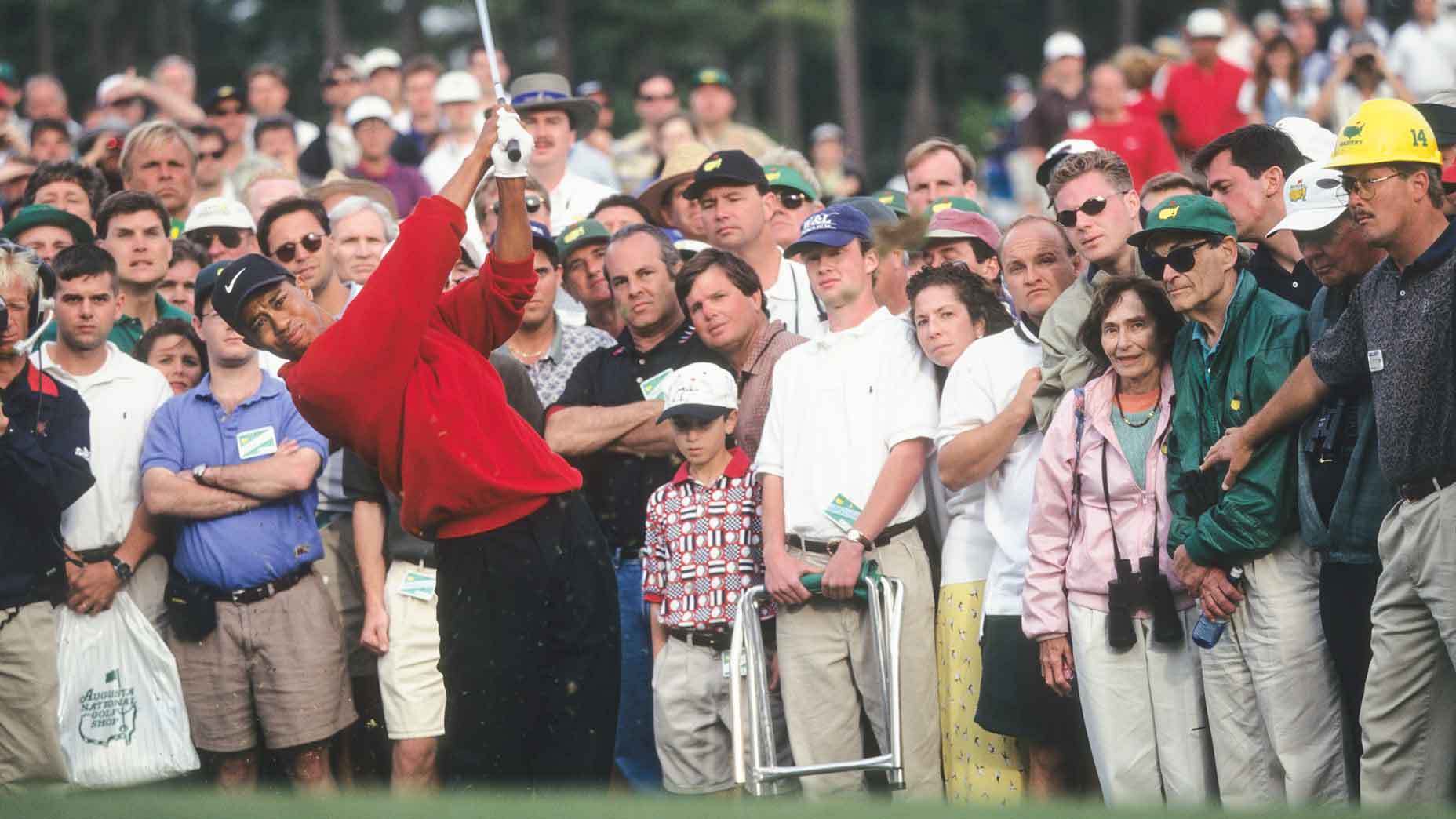

Tiger Woods historic win, in 1997, changed everything.

It’s not that modifications had never been made to Augusta National before; the course had been tweaked on myriad occasions since the birth of the Masters, in 1934.

But Woods’ record-smashing victory (his four-day total of 18 under par was, at the time, the lowest winning score in the history of the event, just as his 12-shot margin of victory was the largest ever) ushered in an era of so-called ‘Tiger proofing’ of the course: changes intended to protect not just par but also the risk-reward drama that was central to Jones’ and Mackenzie’s original design.

Of those changes, none of have been more notable than on the par-5s, all of which have been lengthened since 1997, most recently the 2nd, which has a new back tee for the first time this year.

The modifications underscore a truth about Augusta National: the course is a place of both permanence and change, bent on protecting cherished traditions while holding strong against the modern game.

How successfully has it struck that balance?

Ran Morrisset is the architecture editor at GOLF Magazine. We asked him about the evolution of Augusta National, what the design changes have—and have not accomplished—and the implications of those changes for both players and fans.

GOLF: Before we get to how Augusta National plays today, let’s talk a bit about the original intent behind it. What sort of course did Jones and Mackenzie set out to design?

Ran Morrissett: For starters, Jones and Mackenzie were united in their love of the Old Course at St. Andrews, and that shared vision helped drive Jones to hire Mackenzie. Normally, back in that day, you would have hired Donald Ross to build an important course in the Southeast. But that connection didn’t materialize. And after Jones traveled to California for the 1929 U.S. Amateur at Pebble Beach (which did not go his way as he lost in the first round!), he fell in love with both Cypress Point and Pasatiempo, both MacKenzie designs. Given his experience in California and their shared feelings about the Old Course, Jones ultimately saw Mackenzie as his guy. Famously, Augusta National opened with only 22 bunkers and stood in stark contrast to two of America’s most famous courses at the time, Pine Valley and Oakmont. Jones then established an invitational for his friends, though it’s hard to imagine he had any idea that it would turn into what many refer to as the greatest week in golf.

GOLF: Even in the early years of the Masters, the course was modified in various ways. But when most fans think about tweaks to Augusta National today, they think of the Tiger era.

Morrissett: It’s true that there have been changes since the start, especially by MacKenzie’s friend and associate Perry Maxwell. But after Tiger’s explosive win in 1997, the frequency of those changes increased. And that’s because Augusta National is the only site to host a major every year. They are literally the battleground site for how technology has evolved and how the players have evolved and how you defend against that.

GOLF: Can those defenses be put up without altering the essential character of the course?

Morrissett: Well, Augusta National’s task is made even more difficult because they’re one of the few major sites that plays with four par-5s. By contrast, take the U.S. Open, where the USGA can just say, ‘let’s have two par-5s and turn two of the other par-5s into par-4s.’ That shaves off eight potential shots relative to par over a four-day event. The Masters, from its founding, was meant to present a strategic course with a bunch of risk-reward options. And it would be very different playing the 13th, for instance, as a 445-yard par-4 instead of as a 540-yard par-5. Both are half-par holes, but to me, psychologically, there is a big difference between a birdie roar and an eagle roar. And that is what Augusta is fighting. They don’t want to see driver/8-iron for the 13th. If that’s the norm, then you should call it a par 4, which would break the heart of tens of thousands of fans. I applaud them for keeping the four par-5s as par-5s.

GOLF: But as you say, if too many of the players can reach those par-5s in two with lofted clubs, then they pretty much are par-4s, no?

Morrissett: That’s the conundrum. A guy like Hideki Matsuyama was an example. When he won, in 2021, he was 11 under on the par-5s for the week. His winning total was 10 under. So he was farther under par on the 5s than he was for the entire event.

GOLF: Is it fair to say that Augusta National was simply getting too easy?

Morrissett: In the ‘80s and 90s, especially, it represented the pinnacle of excellence in strategic golf course architecture. We already had majors like the U.S. Open, which presented a more linear examination of golf where you drive it into a 28-yard-wide fairway and then hit to a green ringed by rough. Augusta National represented a far more enlightened form of golf. It was about playing angles. How do you approach certain hole locations from which side of the fairway. It was much more thought-provoking because there were so many possibilities. It wasn’t merely about whether you made a birdie or a bogey. There were genuine prospects for eagles and double bogies. It made the moves up and down the leaderboard all the more nerve-racking. If you’re teeing off on 10 with the lead and you hear an eagle roar on 13, what does that do to your psyche? The Masters brought what is still a unique vibe and excitement, principally driven by its half-par holes on the back, including 11, 12 and 16 in addition to its two famed par-5s.

GOLF: When you’re making design changes to preserve that kind of drama, how do you know if and when those changes have gone too far?

Morrissett: When the excitement ebbs. The 13th has historically played the easiest, and that received the most additional length. The 2nd hole was the second-easiest, and that tee just got moved back and a little more to the left.

GOLF: How do you like that change?

Morrissett: I’m told it’s almost indiscernible to the eye. But you think about the guys who really hammer it off the tee, so many of them play the power fade. That’s their go-to shot under pressure. When you move that tee back and left, a power fade doesn’t work for a right hander anymore. You either have to hit it straight or the preferred draw. I think that’s a cool solution to getting the pros outside of their comfort zone.

GOLF: At the same time, if players are just laying up on the par-5s, that robs the event of excitement, too.

Morrissett: I don’t know what they want the winning score to be. I doubt they were happy when Dustin Johnson won at 20 under par in 2020. That might be viewed as excessive. The easiest way to shore that up is to work on what have been the easiest scoring holes, which are the par-5s. And that’s exactly what you’ve seen since 2020.

GOLF: Last year, we saw a new tee introduced on the 13th. Have we seen enough data from that to know how well that worked?

Morrissett: Not based on a sample of one tournament. We’ll have to wait on that. The other thing that may not get as much attention is that just because they add back tees doesn’t mean that they have to use them. This year, for instance, rain is in the forecast for Thursday. How will that change how the course plays? What the club has done is give itself options. It doesn’t mean you have to play all the tees back and use the hardest hole locations.

GOLF: How would you like to see the course set up?

Morrissett: Augusta National is in a tricky situation. They’re trying to keep the holes where you have to make what Jones called a “momentous decision” going for it on 13. It’s less of a momentous decision with an 8-iron than it is with a 3-iron off a hanging lie. They want to keep the same asks of the golfer that Jones and Mackenzie envisaged. But if you make the course too difficult—and Augusta National is a brutally difficult course—that’s something else. One of the joys of the event is that the players need to decide when to play defensively and when to flip to offense. If everybody is laying up and going into defensive mode, then Augusta’s unique brand of excitement is muted.

GOLF: So the par-5s have to remain gettable.

Morrissett: It doesn’t really matter to me how long and difficult they want to make the course on Thursday and Friday. But come Saturday and Sunday, if you want the most memorable moments, then there have to be eagles and doubles, which can help foster wild swings coming down the stretch.

GOLF: Do you think any of that has been lost in recent years?

Morrissett: Last year, wasn’t it Scottie Scheffler who said that if he didn’t hit a good drive on 13, he was just going to lay up? You never heard a conversation like that in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Everybody knew that you had to get after the par-5s to win.

GOLF: The par-5s aren’t the only holes that have been tweaked in the Tiger-proofing era. The 7th and the 11th, for instance, have been stretched back and tightened. How do you feel about changes like that?

Morrissett: Bearing in mind what the original vision was for a wide course with lots of interesting playing angles, with par defended at the green and in the orientation of the green relative to the fairway, the advent of chutes at Augusta is off-putting to me. My favorite event of the year is watching the Augusta National Women’s Amateur, where a hole like 13, they don’t have to tuck the tee back into the chute. They play the tee right off the 12th green, and it’s essentially the same wide vista that Jones and Mackenzie would surely recognize.

GOLF: It’s been said that one of ironies of the Tiger-proofing era is that it has actually worked in favor of the bombers instead of a defense against them. Do you think that’s true?

Morrissett: If you look back over the past 30 years or so, one of the cool things is how many different types of players have won the Masters. Guys like Ben Crenshaw and Mike Weir and Zach Johnson and Trevor Immelman. Patrick Reed is not exactly a bomber by Tour standards. It wasn’t just Tiger and DJ and Scottie Scheffler and Jon Rahm. But guess what? Those are four of the last five winners. It will be interesting to see moving forward whether these changes are narrowing down the field to where you have to be a bomber to win.

GOLF: It’s hard to strike a balance.

Morrissett: Augusta is held hostage by its own fabulous history of creating so many indelible moments. I have never seen a better sporting event, let alone a better golf event, than the ’86 Masters. We can look back at that and think of 25 shots that are just etched into our memories, both heroic shots and calamities.

GOLF: Nicklaus’ eagle on 15 comes immediately to mind. And his near ace on 16. And his ‘Yessir’ putt on 17. What calamities do you have in mind?

Morrissett: Seve Ballesteros is my favorite golfer of all time. He was on absolute fire on the back nine and it looked to the whole world like he was going to win the event after he eagled the 13th. Then roll the clock forward and he’s standing on the top of the hill at 15, and the roars from Nicklaus up ahead were still ringing through the pines, and Seve hits a horrible shot into the pond at 15. Greg Norman also had a chance to tie or even outright win on 18 but he fanned his approach right and couldn’t get up and down.

GOLF: In recent years, as additional changes have been made to Augusta National, the course has also dropped slightly in GOLF Magazine’s rankings. Does that suggest to you that protecting a course against elite players runs counter to great design?

Morrissett: Is doesn’t have to. It is the manner in which you go about doing it. If the range of possibilities is going to shrink as opposed to expand, and people settle and play defensive golf, then a spark will have been lost. It’s that ability of being able to switch between defense and offense, of having to aim away from the flag on 12 and then flip it back to go after 13, 15 and 16, when the pressure is excruciatingly high. That’s what makes it such a study in human psyche. That’s when it can become more than golf, and you get an insight into what a person is made of.