Work the ball towards or away from trouble?

Getty Images

At risk of starting the week this week’s column going off on a separate tangent, this weekend we were treated to exactly the kind of thing golf broadcasting needs more of: A lean into the nerdy, nitty gritty details that pros spend their lives perfecting. All too often that gets glossed over without much debate or explanation, which is a shame, because that’s where the gold is.

Saturday was a great example. We had six-time major champion Nick Faldo piecing apart different ways to attack Muirfield’s 186 yard, par-3 16th hole with his idol and 18-time major champion Jack Nicklaus. The pin was tucked middle-ish left on Monday, which kicked-off a discussion between the two legends: What’s the best way to attack this hole?

Let’s break down the key points — and what the rest of us can learn from it.

Work the ball towards trouble…

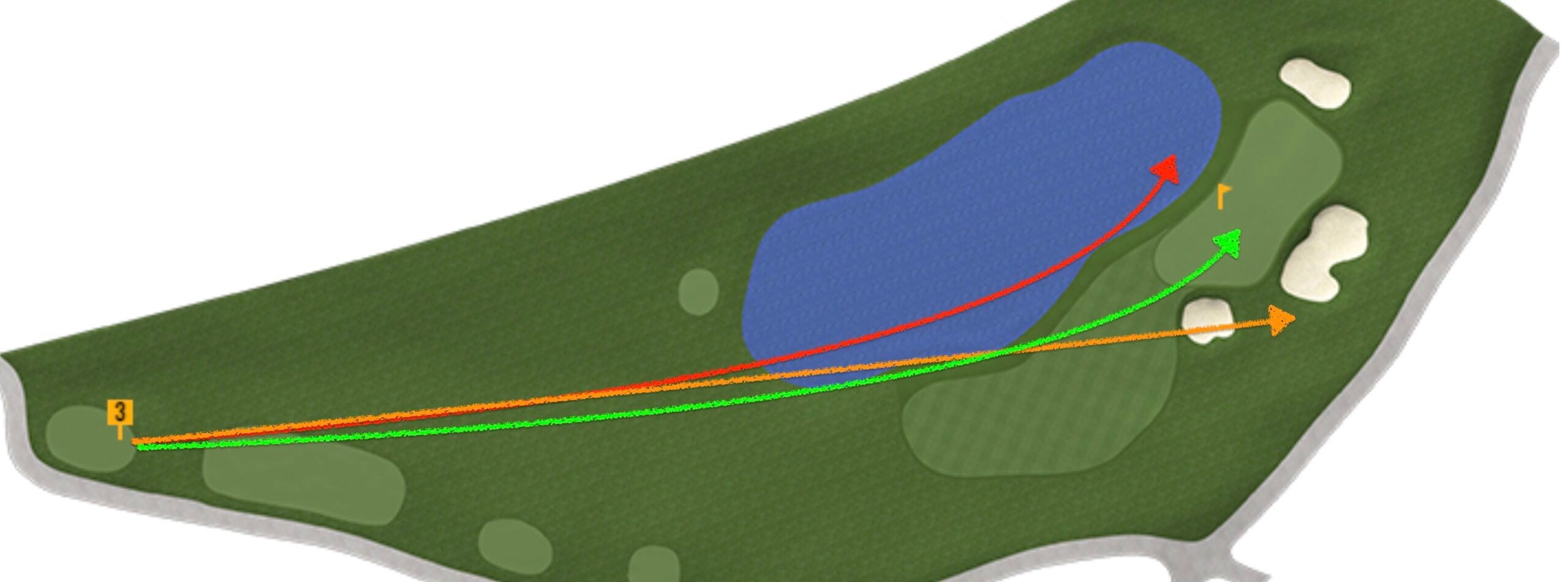

Convention says to work your ball towards trouble.

PGA Tour

My colleague Nick Piastowski did a great job reporting on the full discussion here, but Nicklaus was categorical that he thought the best strategy on this hole was to aim for the middle of the green, and hit a draw towards the pin.

“Don’t ever aim the ball at trouble,” Nicklaus said. “Don’t ever aim the ball at out of bounds. Don’t ever aim the ball at a lake. You always aim away from it. And if you have to play back towards it, make sure that you can’t hook it enough to get there or make sure you can’t fade it enough to get to it.”

This is the conventional advice that pros and teachers say when shaping the ball: Work the ball towards the danger. Indeed, even though Faldo was playing Devil’s Advocate on this occasion, this is the strategy even he used during his prime, as he wrote in his book “A Swing for Life.”

“If the pin is cut towards the back left-hand corner of the green, my instinct is to fire a shot for the middle of the green with the a draw. On the other hand, if I face a shot to a flag cut tight behind a bunker, in the front right quarter of the green, I play a fade. In both cases I aim for the fat part of the green, and let the ball work towards the pin. That’s the key.”

The reason why this advice has become so textbook is because even though the ball is technically moving towards danger, it’s doing so as it slows down. Plus, it gives you a meaty margin for error along the way: You can hit anything from a block to a perfect draw and each of those shots will be fine. It’s why you see so many pros use this strategy for tee shots on doglegs. Best case they’re around the corner and have a shorter club in; worst case, they’re safe but have a longer club in.

It’s only when you drastically over-curve your shot that your ball will find the really bad stuff, which is a tradeoff most pros make, because golfers generally undercook the amount of curve when they’re trying to work the ball.

Except, like everything in golf, that’s a general piece of advice. Like all rules, they’re made to be broken.

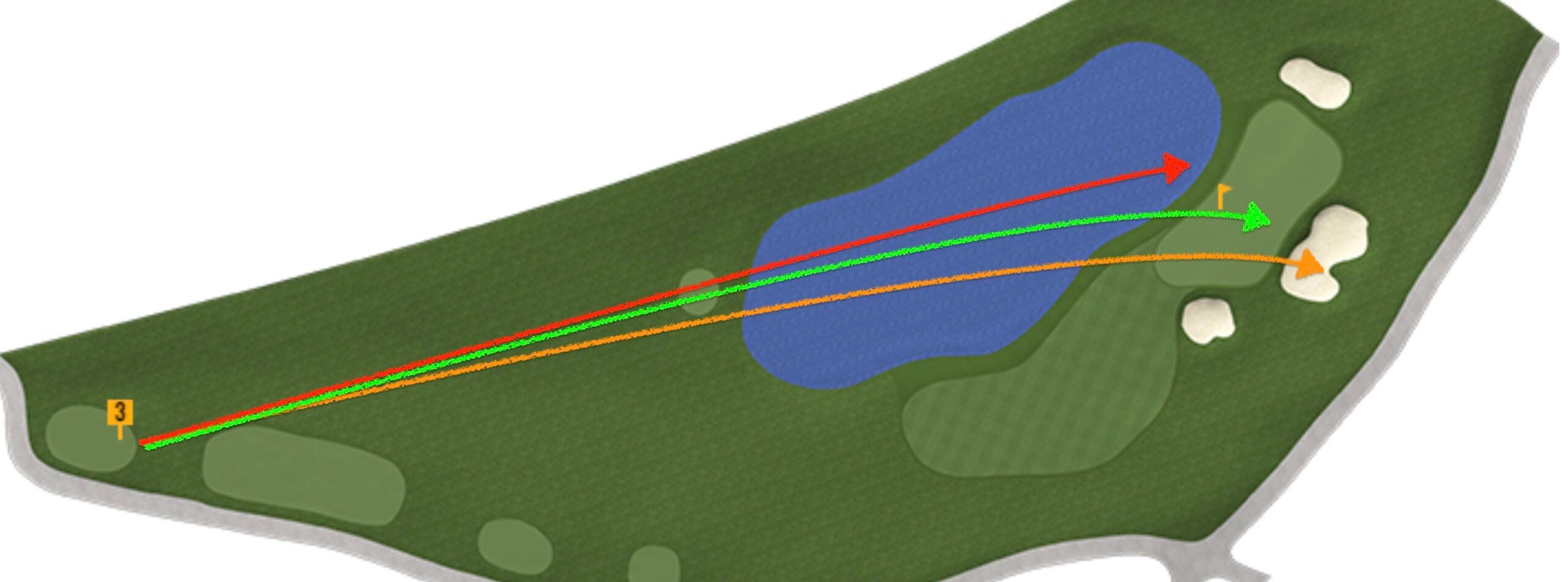

…but there are exceptions

But if you’re comfortable with a specific shot shape, maybe Hogan’s strategy is best for you?

PGA Tour

One of the men who Faldo cited in his discussion was Ben Hogan who, famously, would work the ball away from trouble. So, if there was out-of-bounds left and safety right of it, Hogan would aim straight at it and hit a fade back towards safety. In his mind, this would help him commit to the shot — after all, when you need you need to hit the ball to the right, you’re probably going to hit the ball to the right. And even if you aim for a fade and hit a giant slice, you’re still safe.

But while pros generally default to the conventional advice, most end up adopting a hybrid model. They work the ball towards trouble, but they’ll often choose to do the opposite for two different reasons.

The first is perhaps the most common: It depends on what the wind is doing. If, using the example of Muirfield’s 16th hole above, the wind is blowing severely from right-to-left towards the water, hitting a draw would have the effect of riding the wind and sailing uncontrollably into the lake. Pros, in this case, will often chose to hit a cut back into it, so their ball battles the wind and ends up flying relatively straight.

The other reason pros may disregard the textbook on this is what Faldo was alluding to: When the shot that convention would suggest, quite simply, doesn’t suit their eye. The best recent example came on the 6th hole at the PGA Championship where Rory McIlroy, among others, aimed out of bounds and hit a cut into the fairway of the dogleg left par 5.

“I’m a little more comfortable hitting the driver left-to-right at the minute,” Rory said of the 6th hole. “I feel like my body works a little better; I can be more aggressive with my body. The body doesn’t stop and arms go. Some of those right-to-left winds today off the tee it was nice because I could just aim the driver up the middle of the fairway, hit like a nice hold against the wind.”

This approach is becoming increasingly common on Tour nowadays, and you’ll often see it when players have one preferred shot shape that they try to hit whenever possible. Hogan, for instance, was a legendary fader of the golf ball, so it makes sense that he would feel comfortable aiming at trouble and hitting his signature fade and moving his ball off of it.

As for what you should use? Only you can answer that. But think about what your preferred shot shape is, think about what your misses are — do your little fades tend to turn into slices or pulls? — and factor in the wind. Once you’ve done that, it’s time to stop thinking, and start swinging. Whatever path you choose, the key is to swing with confidence. After all, even the ‘right’ shot is the wrong one if you don’t believe in it.