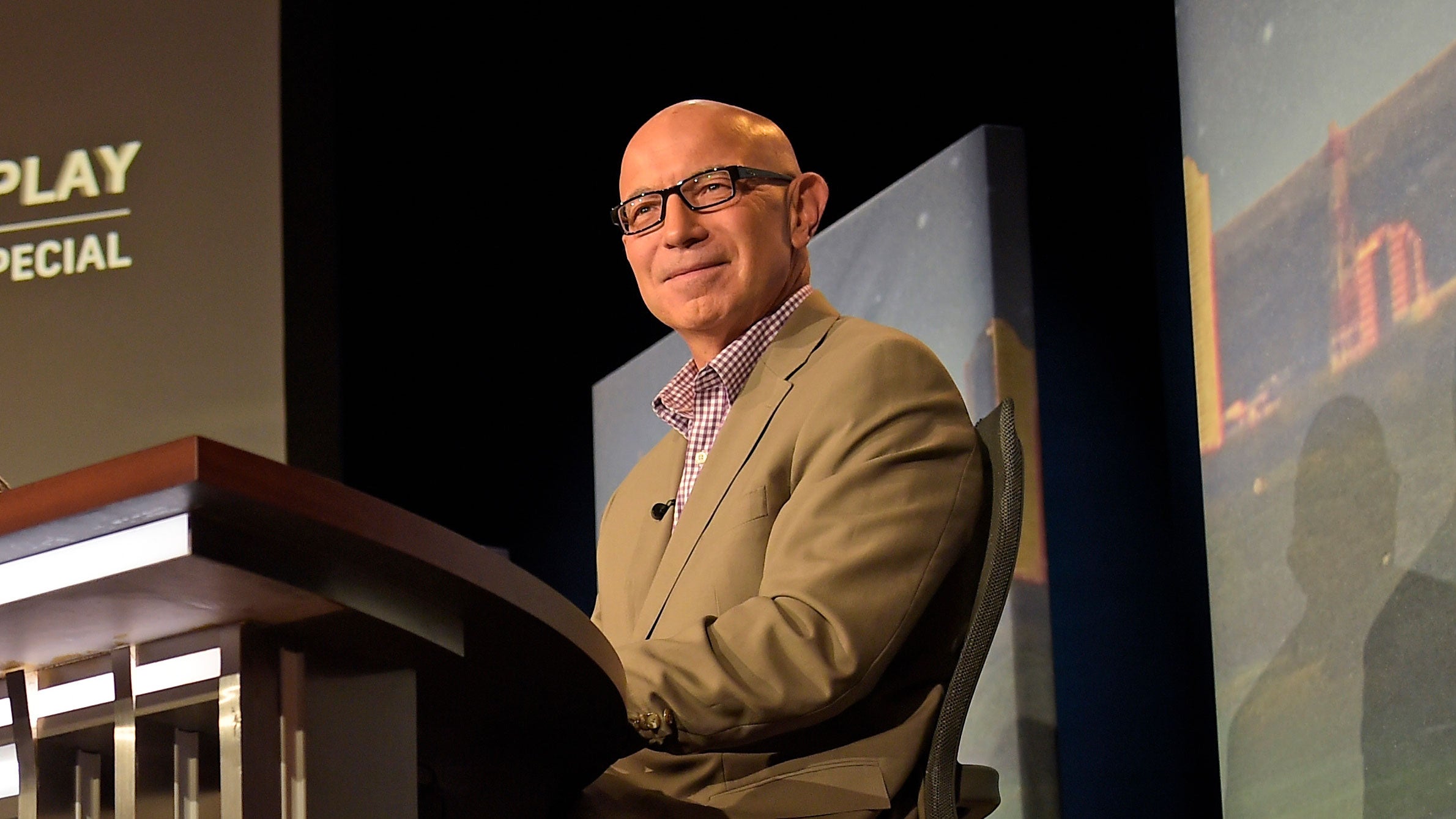

Tim Rosaforte at the Golf Channel desk.

getty images

To borrow a joke from Tim’s old colleague, David Feherty, I feel sorry for his disease. Whatever diseases visited Tim Rosaforte, you know he did everything he could to destroy them. That was his nature. You can imagine him, unshaven and smelly, as a University of Rhode Island linebacker, in the ’70s, terrorizing whomever came his way.

But, in the end, disease doesn’t play fair, and multiple ones ganged up on him, and took Tim from a family he treasured and the games and the people he loved: golf and golfers, reporting and reporters, gym and gym rats. As the Beatles sang and I paraphrase, the more you give, the more you get. Tim gave and gave and gave.

He had a chip on his shoulder as so many accomplished athletes, and accomplished anythings, do. He started out, after college, as a reporter. But what he wanted to be a writer. You know, it was a time and a place. He grew up on Dan Jenkins and that whole thing. And by the mid-1990s he had made it to Sports Illustrated.

Tim Rosaforte with Tiger Woods at a 2007 awards dinner.

getty images

But he was too decent to take all the information he had in his notebooks and, as a writer must do, make it his own. And that’s what led to his second professional life, at Golf Channel and NBC Sports, where he invented something that had not existed: golf-on-TV as a news beat.

There’s a great book on politics that’s too long to read by Richard Ben Cramer called What it Takes. Here’s one lesson from the book’s 1,000 or so pages: If Joe Biden won’t talk to you, or give you the insight you need, find someone else. And that’s what Rosaforte did in his golf work on TV. He gave us the wife, the girlfriend, the teacher, the college coach. The late grandmother who gave the golfer her first putter, in the bassinet. This one’s for you, Grammy!

But always — always! — he was honest and accurate and fair.

NBC golf producer Tommy Roy or others would cut from Bob Costas to Tim and he’d have a minute, notebook in hand, and he made every word count.

Tim thrived on order and discipline, looking the part, acting the part, doing things the right way. Golf gives you a lot of opportunity for that. He liked the sense of manners and propriety you sometimes see at old-line clubs, like a Winged Foot in suburban New York City, near Tim’s childhood home, and Seminole, in South Florida, where he lived most of his adult life.

He played all the game’s shrines as a guest and there was something endearing about his keen outsider’s interest in these places. But of all the many courses where I saw Tim over the years, the place he seemed most at home was Bay Hill. “This place is Arnold,” he once said.

Well, Tim, in his way, was Arnold. Strong, physically and otherwise, straight-forward in manner, precise in his speech, organized in his work, fair and warm and decent to the many, many people who knew and admired him.