For every professional golfer, taxes are par for the course, but many elite players also have numerous other payouts to make from each check.

Getty Images

Back in late April, a week after last year’s taxes were due to Uncle Sam, Talor Gooch won a LIV Golf event in Adelaide, Australia. His post-victory comments on a golf podcast made as much news as the victory itself.

“I am by no means complaining,” Gooch said, merely noting that “it sucked that 47 and a half percent” of his $4 million top prize was withheld for Australian taxes, so “once you cut it all up, let’s just say that it’s a lot less than four.” It was, the Midwest City, Okla., native said, “a little bit disheartening.”

Whether one saw this as the second coming of Marie Antoinette’s infamous “Let them eat cake” or an all-too-relatable lament of workers everywhere, it brought to the fore a question every golf fan has had watching an oversize check being hoisted aloft: How much does the winner actually take home? Trophies and record books are great, but what’s the bottom line?

Gooch will have known from his prior stint on the PGA Tour, where he won the 2021 RSM Classic, that taxes aren’t just the price we pay for a civilized society (per Oliver Wendall Holmes Jr.). They’re par for the course on any circuit for winners and for the vanquished (except for the missed-cutters who make bubkes for the week… something Gooch needn’t worry about anymore on the no-cut LIV — nor competitors in eight designated no-cut, limited-field, “elevated” PGA Tour events, too, starting in 2024).

But, when it comes to taxes, what is par for the course?

Well, mate, each foreign country has its own rules; there can be foreign withholding in Mexico (7 percent), Canada (15 percent), and the UK (18 to 20 percent) too. If the tournament is on American soil, it likewise depends on where the win occurs.

“California is the toughest,” says one veteran golf agent who requested anonymity. “It withholds 7 percent of the check right off the bat.”

Other places that typically withhold include Louisiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina and South Carolina, and Ohio’s Dublin/Columbus withholds city taxes for The Memorial tournament. While other states, such as Hawaii, Florida, Arizona, New York and Texas, don’t withhold, that doesn’t mean there is no tax filing requirement later.

Regardless of the host setting, the PGA Tour notes, it is “required to adhere to all local, state, federal and foreign laws and regulations set forth by government agencies and their related tax authorities when income is paid to professionals. PGA Tour withholds taxes and reports on all income, where required by law.”

Golfers and their accountants and advisers know full well that they, too, must mark down the right numbers on the scorecard. Joe Pros wishing to decrease their tax burden do have an option that should also be familiar to Joe Blows, namely, put some of that pretax income into a retirement plan. According to the PGA Tour, its members, as well as those on PGA Tour Champions and the Korn Ferry Tour, have the option to participate in an elective retirement plan in which they can defer prize money into a retirement account, with deferrals limited by annual IRS limits.

“We recommend 100 percent of our clients max out that elective plan,” says Joe McLean, senior managing director for MAI Capital Management, which counts three-time PGA Tour winner Cameron Champ among its clients. “That’s ‘old person money,’ but it’s important to do that as early as you possibly can to use the time value of money. Check the box, make sure you’re paying yourself first and save on taxes too.”

As such, McLean’s firm always immediately puts sufficient prize money into a tax savings account to earn interest on it until those taxes are due.

“There’s very little guaranteed money in golf, and the income will spike up and down quite substantially,” he says. “If you don’t stay hyper-organized in terms of the money going in and out of your life, you can find yourself not having saved enough money to pay your taxes.”

GOLF

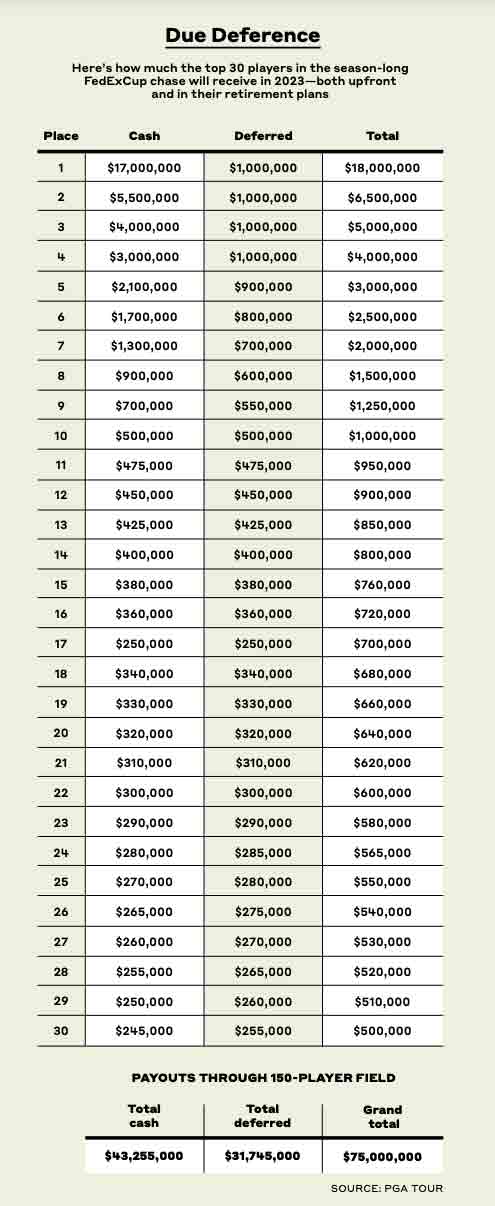

The PGA Tour also sponsors nonelective retirement plans — the FedExCup Bonus Plan, Cuts Plan ($4,500 for each of the first 15 cuts made in a season, twice that for each additional cut) and PGA Tour Champions Plan. Contributions to these are in addition to any prize money earned and made after the season concludes. Speaking of which, win the FedExCup’s $18 million top prize in 2023 and $17 million is in cash and $1 million goes to the player’s FECBP (see chart above).

Withholdings notwithstanding, our tournament champion is still looking at a healthy lump sum. While there’s something appealingly primal about those big poker tournaments where organizers dump the millions at stake onto the table before the last two competitors play Heads-up, professional golf is a more buttoned-up affair. The Tour pays its players via several common payment types, including direct deposit, wire transfer and check, underscoring that it “makes every effort to minimize paper waste and encourages electronic payment to all professionals.” (Waste management: It’s not just for the Phoenix Open.)

Golfers and their accountants know full well that they, too, must mark down the right numbers on the scorecard.

To those pros, cleanliness is no doubt a distant runner-up to timeliness when it comes to getting their dough. The PGA Tour pays professionals for all income — official, unofficial or secondary event money — net of any withholdings as required by law and retirement contributions if elected “as soon as commercially feasible.” Typically, that’s by close of business the Tuesday after a Sunday finish.

“Look in your account on Wednesday and it’s there, like clockwork, just like your GOLF magazine paycheck,” says the agent, kind enough not to add, “only with more zeros.”

Taxes and retirement plans are far from the only takeaways from the take-home side of the winner’s ledger. For a win, it’s industry standard for 10 percent of the top prize to go to the bagman. That’s above and beyond the caddie’s weekly base fee, which ranges from $1,000 to $2,500 or so, and a step up from the 8 percent bonus for a top-10 finish and 6 percent on everything else in the money.

Nor does victory mean a week off from the player’s normal expenses, just a greater ability to pay them. To invert the old saying, failure may be an orphan, but success has a thousand fathers (John F. Kennedy, post–Bay of Pigs fiasco, via the historian Tacitus). Swing, short-game, mental and data coaches still need to be paid. And they might not only expect a little something extra, you know, for the successful effort, but be contractually obligated in that regard — many now work on a performance-based percentage rather than a weekly retainer. Then there are physical trainers, massage therapists, personal chefs and such to keep a player healthy.

“Professional service fees might be as much as 8 to 13 percent of a player’s earnings in a normal week,” notes McLean. (He sometimes recommends supplemental disability insurance beyond the Tour’s $10,000 a month plan, because an injured player’s bills keep coming regardless.) Not all Tour players have all these workers in their retinue, but most have at least some, sometimes, and they can each run $2,000 to $5,000 a week.

So, in sum: To the winner go the spoils (William L. Marcy, U.S. politician) … and, yes, the taxes and other bills too. Still, don’t be disheartened, champ. It’s safe to say that going the deepest into red numbers for the week on the course leaves your bank account well into the black.