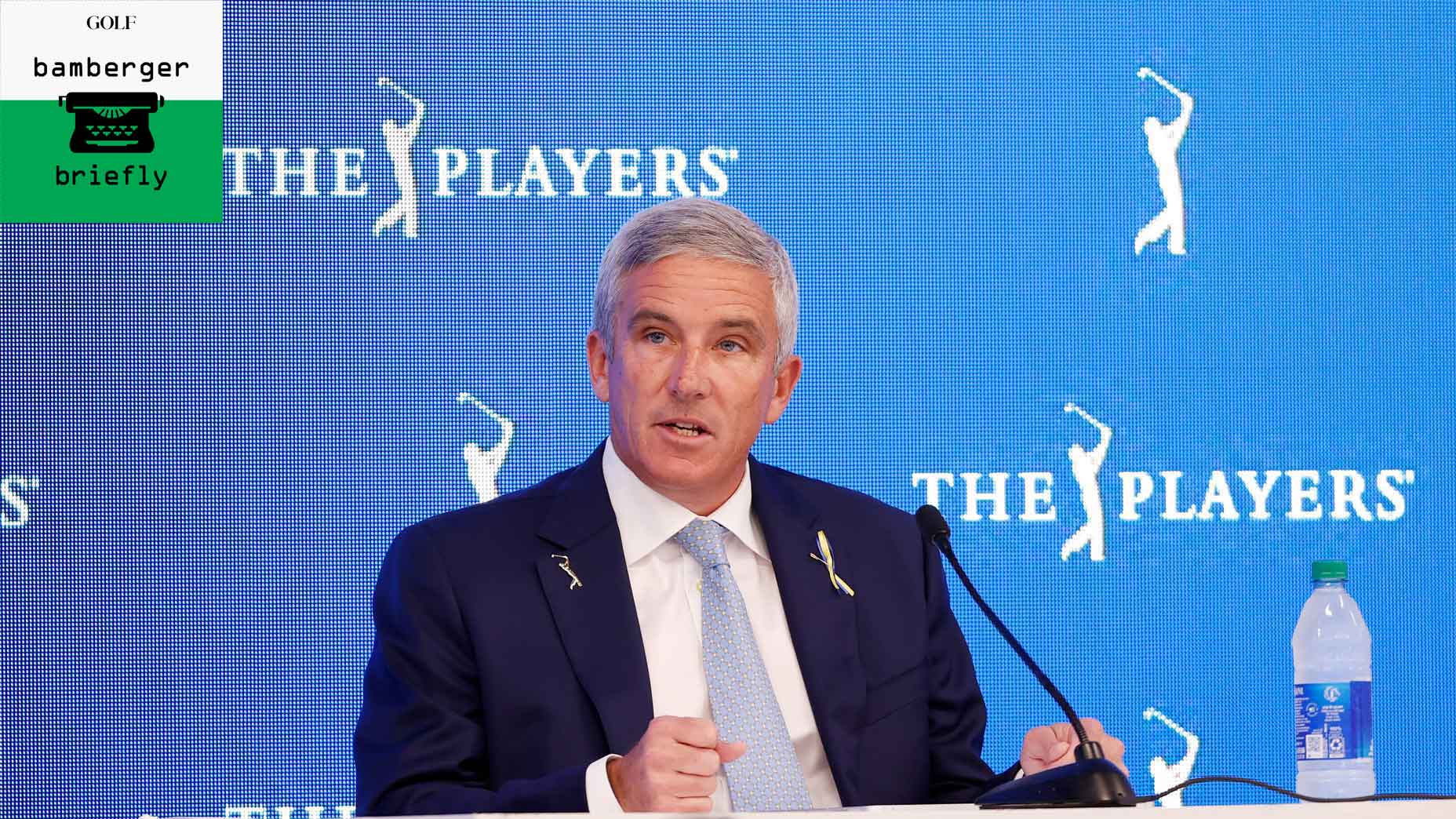

Over the last two complicated years, PGA Tour commissioner Jay Monahan has had to lead — and adapt — on the fly.

Getty Images

PONTE VEDRA BEACH, Fla. — You’re a golfer. You know how it is. You have the oddest sort of memory. You recall the holes you played and the shots you took like most people can remember their children’s middle names. Plus, the weather. Always the weather.

At the end of 2000, I had a semi-lengthy interview with Tiger Woods. He was going to be Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year, the first person to get the honor for a second time. My impression was he could not have cared less.

When I asked him about his nine-shot win in the British Open at the Old Course, he kept going back to the weather. He couldn’t believe how calm and warm it was for four straight days.

Enter Jay Monahan, the PGA Tour commissioner. This year’s Players Championship will end on a Monday, as it rarely does, but also grandly, as it always does. But for three days the only story was the weather. And what Monahan could recall, at the drop of a hat, was the weather on this occasion two years ago. Four warm sunny days, light breezes, no rain. One day of golf. The tournament was canceled after one round.

Rory McIlory, now the chairman of the PGA Tour’s Player Advisory Council, said, “It’s going to get worse before it gets better.” That was prescient.

McIlroy has Monahan’s ear and vice-versa. Both have a nice sense of humor. At a press conference before the tournament, McIlroy said that the Tour should be more open about announcing suspensions and fines. (It’s notoriously tight-lipped about these matters.) Later, at another press conference, when Monahan learned what McIlory’s position, the commissioner said, “Effective immediately, Rory McIlroy is suspended.”

Being the PGA Tour commissioner has never been more complicated and it started getting really complicated two years ago, when the Players was called after 18 holes, on account of Covid. None of Monahan’s three predecessors — Joe Dey, Deane Beman, Tim Finchem, all members of the World Golf Hall of Fame — have had the long series of challenges that Monahan has faced. Finchem’s 22-year run as commissioner, from 1994 to 2016, basically overlapped with Woods’ career.

In fact, Finchem was inducted just before Woods at the Wednesday-night ceremony in the Tour’s gleaming glass-and-stone headquarters that would be right at home in Milan. You could say Finchem built the new headquarters, given how the Tour’s revenues increased under his watch. But you could say Woods built it, too. Monahan talked about both men at the ceremony.

Here’s an abbreviated list of the issues Monahan has faced that no other commissioner has:

The onset of the pandemic in March 2020.

George Floyd’s death in May 2020 and the racial-unrest awakening it wrought.

Multiple failed Covid tests at the RBC Heritage Classic at Hilton Head tournament in June 2020.

A total reworking of the 2020 schedule, on the fly, throughout 2020.

Patrick Reed’s embedded ball controversy at Torrey Pines in January 2021.

Woods’ terrifying car crash in February 2021.

Greg Norman’s reported planning of a rival international golf league over the course of 2021 and 2022.

Phil Mickelson’s recent, published comments about the PGA Tour (the hand that has fed him) and that proposed league (the hand that could).

Yikes!

This is a roundabout way of saying that Monahan has had his hands full and then some. He has had to protect his turf and he has had to be open to change. And he has done both.

Joe Dey, before becoming the first PGA Tour commissioner, had been the longtime executive director of the USGA. In 1968, when the PGA Tour was breaking away from the PGA of America, the fledgling Tour needed someone with unimpeachable credentials. Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus did not start the movement from the touring pros to break away from the PGA of America. Doug Ford and Bob Goalby were much more active in the effort. But Palmer and Nicklaus played a significant role in bringing Dey to the PGA Tour. Dey, first and foremost, was an ethicist. The starting point for the Tour’s credibility with the public and with the corporate sponsors was that we believed the scores the players said they shot. That was the necessary starting point. He served from the start of 1969 through 1974.

Dey’s successor, Deane Beman, had a 20-year run as commissioner. Beman was a former Tour player with four wins. He thought like a Tour player. He knew what players, his constituents, wanted: more playing opportunities for more money. And that’s what he worked toward.

Beman’s successor, Tim Finchem, was a lawyer who had worked in the Carter White House as an economics advisor. He approached his job as the most sophisticated type of politician and negotiator, keeping his cards close to his starched shirt and always several steps ahead of others.

Monahan became commissioner in January 2017. He came to the PGA Tour with a background in sales and marketing and administration, and he rose on those things.

So consider this progression of the commissioners, and excuse the brevity:

An ethicist. A player. A politician. A marketing man.

And then came the last two years.

Baseball has had 10 commissioners: Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Happy Chandler, Spike Eckert, Ford Frick, Bowie Kuhn, Peter Ueberroth, Bart Giamatti, Fay Vincent, Bud Selig and Rob Manfred. The first eight of them were, to different degrees, national figures because baseball was the national pastime and each had three main constituencies: the players, the owner and the fans. Selig was a former owner and his allegiance, in this reporter’s opinion, was overwhelmingly to the owners. Manfred, I would say, the same.

The role of the PGA Tour commissioner is different. The four commissioners serve at the pleasure of the players. The PGA Tour, under its charter as a not-for-profit organization, exists to promote professional golf.

But something has changed over these past two complicated and difficult years. Monahan must serve the players, but he must lecture the players, on the sanctity of the rules, the dangers of Covid, the threat of a competing tours. He has had to find money and spend money to keep the players happy knowing that the most fans couldn’t be less interested and, if anything, are turned off by it.

He has had to keep corporate sponsors interested in trying times. He has had be to an ethicist. He has had to think like a player. He has had to be a politician and a marketing man. He has had to be more like Landis and Ueberroth and Giamatti. Of course there have been bumps along the way. But he’s kept his hands on the handlebars. He’s been a commissioner.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com