The Beatles had a feeling, just like golfers do.

Sir Nick met Sir Paul only once, but it was memorable. It was at Royal Albert Hall. Yes, that one.

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall.

Elton John made the introduction.

Nick Faldo was pleased to learn that the Beatle, an icon of our culture, knew who he was. “Paul McCartney,” Faldo said the other day. You could hear a hint of awe, as Faldo said the name. You know the accent, from his many years in many CBS towers. “So that was a nice bit.”

But it’s not surprising that McCartney would know Nick Faldo’s name, and the sporting life behind it. He reads the paper. He likely owns a telly. We’re not talking Dylan here.

McCartney grew up in Liverpool, a golf town if ever there was one. As a teenager, he would walk across a course — Alerton Manor GC — to get from his house to John Lennon’s. In the summer of ‘56, when McCartney was 14, Peter Thomson of Australia won the Open at Royal Liverpool. (Talk about your world tours. Other players in the top-10 that year were from Argentina, Belgium, England, Ireland, South Africa and the United States.) McCartney is a soccer — well, football — fan and, despite his immense and global fame, quite regular in demeanor and manner. Earth-bound.

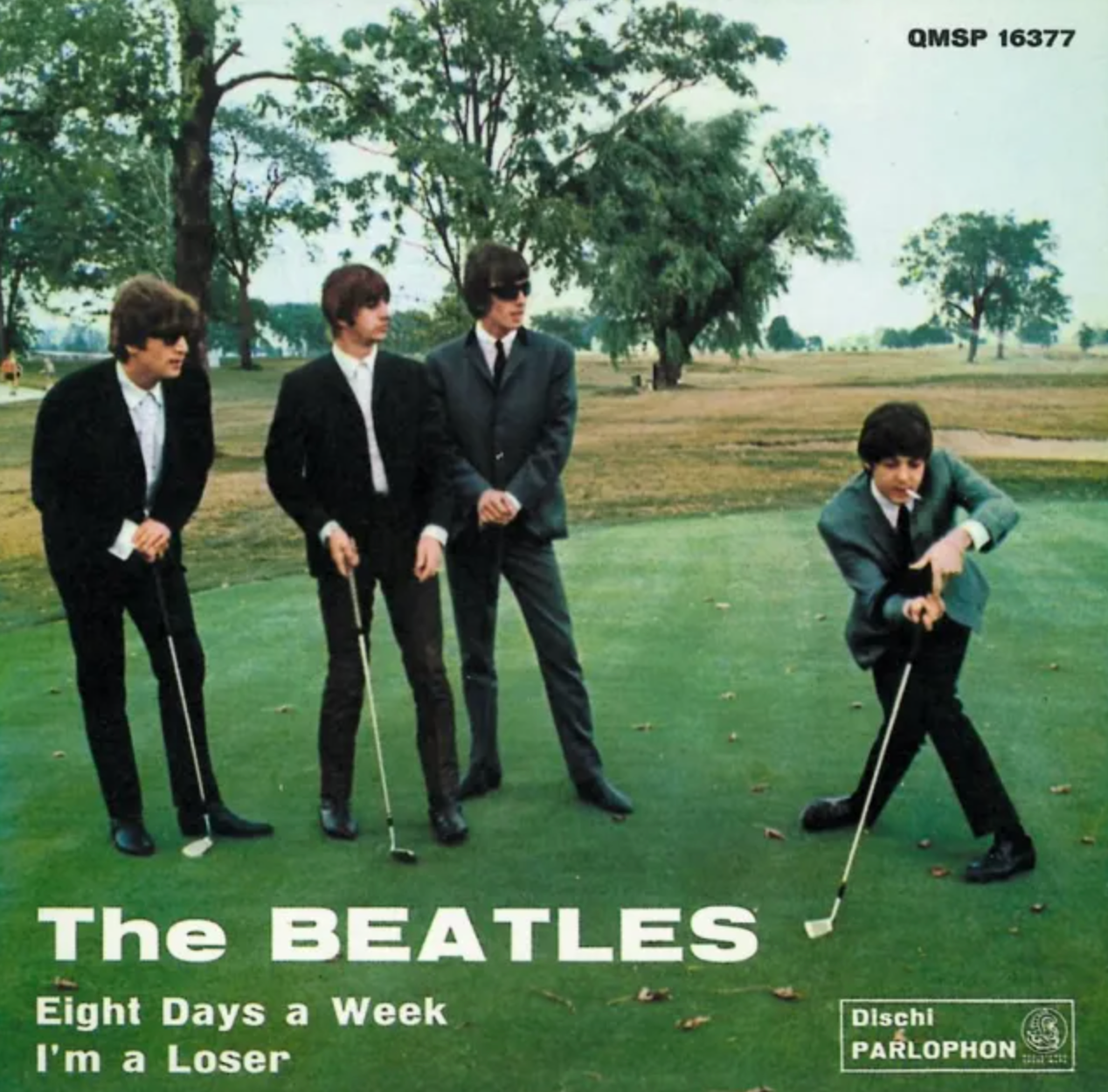

The Fab Foursome: Paul McCartney, far right, and the lads used golf as a backdrop for this 1964 album cover.

You might recall Chris Farley, on “Saturday Night Live” years ago, and an interview-as-bit he did with McCartney.

Farley: “Remember when you were in the Beatles?”

McCartney remembers.

“And you did that album ‘Abbey Road?’ And at the very end, the song that goes, ‘In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.’ You remember that?

“Yes,” McCartney says.

“Is that true?”

“Yes, Chris, in my experience it is,” McCartney says. “I find, the more you give, the more you get.”

And Farley stares into the camera and mouths, “Awesome!”

So Nick Faldo, quintessential Englishman golfer, winner of three British Opens (each in Scotland), met Paul McCartney and learned that McCartney was aware of him. A day in the life for McCartney but a memory forever for Faldo. It was in 1997, at a benefit concert at Albert Hall after an earthquake on the island of Montserrat, a British territory. A week or so later, Faldo flew to Spain, as a captain’s pick on Seve Ballesteros’s Ryder Cup team. Faldo was 40. Seve, in his own way, was a Beatle. Hard to say which won, but he had the hair and the artistry. He was an original. Faldo has a certain awe for him, too.

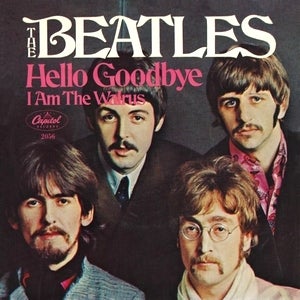

Thirty years earlier, in 1967, in the distant suburb of London where he was raised, Boy Nick bought his first record. It was a single by the four lads, Englishmen a half-generation older than Nick: Paul (McCartney), John (Lennon), George (Harrison) and Ringo (Starr). That was in 1967. The band, by Lennon’s reckoning, was then “more popular than Jesus.” Faldo was 10. His first round of golf was four years away.

“The first 45 I ever bought was ‘Hello, Goodbye.’ That was the A side,” Faldo said in a recent 55-minute phone interview about his long interest in the Beatles. His parents loved music, but their taste ran to classical music and opera. Their only child went off in his own direction. “The B side was ‘I am the Walrus.’”

The first 45 in Nick Faldo’s collection.

For you youngsters: a 45 was a once ubiquitous miniature vinyl record. The number is a reference to the revolutions per minute the record would make on a turntable. A 45 typically had one song on one side — the A side was meant to be the more commercial of the two — and a come-along-for-the-ride B side. But sometimes music execs would get things wrong. The Beatles were so far ahead of the music curve it was impossible to predict how their music would land.

Faldo half-sang the familiar B-side chorus of that single:

“I am the egg man. They are the egg men. I am the walrus. Goo goo g’joob.”

He offered this commentary: “Kind of funny lyrics, they are.”

Indeed they are. Inscrutable, really.

There was a preamble to this phone interview. It came last month, when I saw Faldo at a golf event and asked if he had watched “Get Back,” the new eight-hour, three-part Beatles documentary, all of it shot in a one-month period, in January 1969, culminating in a brief rooftop concert with a shelf-life of forever. They sing, among other numbers, “Get Back,” “Don’t Let Me Down” and “I’ve Got a Feeling.”

Faldo, on that December day last month, was at the Ritz-Carlton Golf Club in Orlando, where he was playing with his son, Matthew, at the PNC Championship, the father-son event. Faldo had watched the doc. He had devoured the whole thing in two heaping portions.

I told Faldo it took me about 12 hours to watch the eight, because I kept hitting the rewind button, to hear something again. Part of it is the Scouse accent that runs through it. That is, English as spoken by the native population in Liverpool, where each of the lads was raised. Statements come out as questions and there’s a guttural German quality to the English, yet also something very Irish and sing-songy in it. Collectively, their speech is lively and incisive, except when it’s willfully obtuse.

The whole thing, except for the rooftop concert, is all behind-the-scenes stuff. The camera is there but nobody is playing to it. Sometimes it’s actually hidden.

It brought to mind for me Tiger’s profane gum-toss, after his wild tee shot on 13 in the last round of the 2019 Masters. “Ahh, I f—ing slipped,” Tiger said, throwing his gum in an azalea bush with a righty backhanded toss. You could see the actual man in that moment, and it was spectacular. Something weird happened to that shot, by the way. It was headed for the left trees and finished in the fairway. Real life is weird.

In Orlando, I had asked Faldo if he had ever played Machrihanish, a gently heaving seaside course named for the village where it lies. It’s in a remote part of Scotland called the Mull of Kintyre, a peninsula which dangles off the lower left-hand corner of Scotland like a down-pointing thumb.

“I haven’t been but I know that it’s a pure links, as pure as it gets” he said. I’ve played it. I couldn’t agree more.

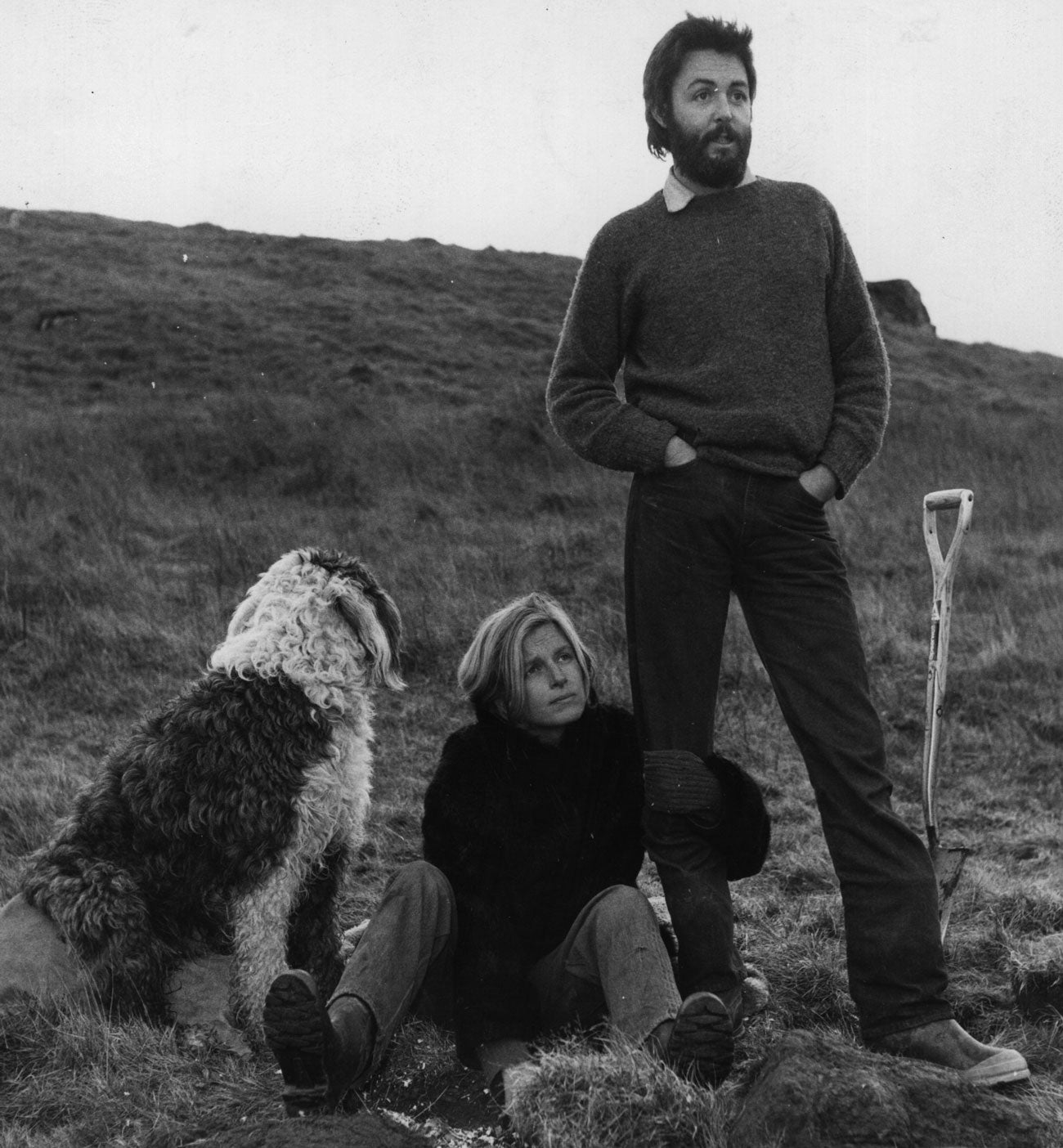

Faldo knew why I was asking. For many years, McCartney and his family, at least at certain times of the year, lived on a sprawling sheep farm near Machrihanish. In 1977, with his band Wings, McCartney recorded a ballad he had written called “Mull of Kintyre.” It sounds so traditional. You can practically smell the nearby brackish sea in it.

The song was never released as a single in the United States, but to this day only three singles have ever sold better than it in the history of recorded music in the United Kingdom. On that list, one spot ahead of “Mull of Kintyre” is the Queen anthem “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

As Faldo and I stood there, near the Ritz-Carlton Golf Club’s 18th green, Faldo sang the refrain of “Mull of Kintyre.” Across the British Isles, it’s a song people know. Faldo as music buff. Who knew? I didn’t.

Faldo and I were both struck by two things, among many others, from “Get Back,” the documentary. For starters, how polite McCartney is to his bandmates, and to the others on hand, as they write and record various songs. Also, McCartney’s immense capacity for work.

“It’s just amazing, to see McCartney sitting there, bass in his hands, working out what will become ‘Get Back,’ but nobody knows that then,” Faldo said. “Ringo just sitting there, silently taking it all in. Paul has, ‘Jojo was a man, Jojo was a man,’ but doesn’t have the next bit yet.”

Ringo’s silence is deceiving. He nods pensively, and that makes all the difference, I’d say. There’s so much silent encouragement there. McCartney is the opposite of the artist as lone wolf. Seve liked to have guys around, when he hit balls.

I asked Faldo if he had ever worked as McCartney does, in that instance. Just show up for practice sessions, maybe in the period when he was reinventing his swing under the watchful eye of David Leadbetter, intent on getting something done, even if he didn’t know what that something might be upon arrival. He said—

Can I pick up that thread in a bit? Let’s take a little side trip first, straight down the Mull on the A83. Beautiful drive.

I went to Machrihanish for the first time in the summer of ’91. According to a journal I’m looking at now, Christine and I, 10 months into married life, spent seven nights there (on the heels of 15 nights in a flat in St. Andrews). I became completely enamored with the golf course and its namesake village and its people. We watched John Daly win the PGA Championship at Crooked Stick in the clubhouse bar, where we ate dinner every night. A new friend gave me a club tie. Maroon, with oystercatchers on it. Wash-and-wear. The Scots are so practical.

It was during our week there that I first heard about McCartney’s connection to Machrihanish.

The Beatles have been in my life all my life, pretty much. I remember an almost pleasant feeling of melancholy washing over me after seeing the movie “Let it Be” when it played in a local theater in 1970, just as we were all learning that the Beatles were disbanding. I think I accepted, as a 10-year-old, that they had run their course.

A year or two earlier, with the help of friends and their older siblings, we would play a certain Beatles 45, backward by hand, to reveal a voice saying “Paul is dead.” At least, that was the claim in the halls of Medford Avenue Elementary School and in select basements. I never heard it. Also, Paul was not dead.

The other day, through FaceTime magic, I interviewed a man named Tom Blue, a 61-year-old Machrihanish member, and a lifelong resident of nearby Campbeltown, about his association with McCartney. Blue met McCartney when he was 17 and went by Tommy. He had been invited to McCartney’s farm, along with some of his musically-inclined buddies, to play with McCartney and Wings as they recorded “Mull of Kintyre.”

The rolling terrain at Machrihanish Golf Club.

getty images

Blue’s mates were pipers, musicians who play the ancestral instrument of Scotland, the bagpipes. Young Tommy played the bass drum, military style. That is, standing up, the tub attached to his belly and secured in place by straps around his back, while wearing a uniform that would look right at home on the cover of the album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

“Leych,” Blue said, or something like that, warming quickly to our subject. “Paul had called Tony Wilson, the pipe major of the Campbeltown Pipe Band, told him about the song he wanted to make, told him to bring in a group of drummers and pipers, about 14 or 15 of us in all, and I was among them.

“It was all really quite quick. We got the song down straight away. Paul was just a lovely guy, seemed quite content with everything. He had a couple dogs with him. He was wearing cowboy boots, brown corduroys and a waist coat.”

“Did he look like a farmer?” I asked.

“Nay,” Blue said. “He looked like a rooker.” Blue laughed.

I asked if food was served at the recording. Not that he could recall. He noted that the McCartneys were vegetarians. “There was plenty of alcohol, though,” he said. Campbeltown was once famous for its whisky. Blue feels McCartney’s song put his remote hometown, and the peninsula on which it sits, back on the map.

They recorded the song and shot a video to go with it at the McCartney farm, called High Park, and at a local beach on Machrihanish Bay, where the surf, in certain moods, can get big enough for serious surfing. (You can practically fall off the first tee at Machrihanish and into the bay.) McCartney had bought his first piece of High Park Farm in 1966 and added more over the years. “I remember Linda coming out of the farmhouse,” Blue said. “She was pregnant with their son, Jamie.”

Blue said that Paul and Linda McCartney were well-liked across Campbeltown and across Kintyre, and that it was not uncommon to see them in town. Blue mentioned a memorial statue of Linda, beside a garden, in the heart of Campbeltown. Blue lives not far from it, in a bungalow near the town pier, his clubs in the boot of his car, ready for a game whenever the mood strikes, even this time of year. His annual golf membership at Machrihanish is 430 pounds — not even $600 — for all the golf he wants on a course that comes out of the sea and a golfing dream.

Tom Blue and his wife and their son and daughter have spent their lives on the Mull of Kintyre. His daughter, Julie, is a piper, and several years ago she was invited to play at a fashion show on a Machrihanish beach at the behest of Paul McCartney’s daughter, Stella McCartney, a clothing designer. Stella was introducing a line of clothing inspired by the Mull of Kintyre and its people. As the show was unfolding, and the pipers playing, Stella tried to reach her father by phone, but couldn’t get him, and she welled with emotion. Linda, Stella’s mother, had died years earlier.

One last thing, before we leave Machrihanish. Tommy Blue is a retired roofer. He worked on the slate roof of the tiny pro shop behind the first tee at Machrihanish. He also did work on McCartney’s farmhouse.

About eight years after “Mull of Kintyre” was recorded, McCartney looked at Tommy as he stood on his roof, slating it.

“Do you remember me?” Tommy said.

“Your face does look familiar,” McCartney said.

“I played the bass drum for you on ‘Mull of Kintyre,’” Tommy said.

“Then that’s it then,” McCartney said.

Faldo said that if modern golf has a Paul, it’s Rory McIlroy, who won his Open at Royal Liverpool, aka Hoylake. Over a larger sweep of time, Faldo liked Arnold Palmer as the McCartney of golf. He said the John Lennon of golf would have to be either Jack Nicklaus or Tiger Woods, for their combination of intellect and innate gifts, two Lennon trademarks. For the George Harrison of golf, Faldo offered Sam Snead, who sometimes said that his knack for golf came from the same place as his knack for music. (He came from a musical family.) Also, Snead was not a talker, at least not on the course. Harrison was often called “the quiet Beatle.”

Faldo struggled to identify a Ringo Starr of golf. Drummers always lead and Ringo does, but he also seems to take his cues from Harrison’s unique rhythms. There’s something magical about it, really. It’s like playing golf with somebody who swings like Annika Sorenstam or Larry Mize. A playing partner with good rhythm will improve yours. I better move on here — I don’t know what I’m talking about, really. It is neat to see Ringo juggle drumsticks, using rhythm with instruments of rhythm. Maybe you have your own candidate: Ringo is to the Beatles as _____ is to golf.

There are other people who are quietly powerful in “Get Back.” One is Yoko Ono (except when she briefly screams full blast into a microphone). She is an extension of Lennon, as he is for her. You needed them both for “Let it Be” to be the LP it is. You know, alchemy. Arnold and Tip Anderson, Palmer’s British caddie from St. Andrews. They had it, too.

Along those lines, may I introduce to you, the one and only Billy P.? Billy Preston, the album’s multi-purpose keyboard player. In the doc, he comes in later than the others, but his spirit lifts the room and the enterprise. His smile is infectious. His love for the fellas, and theirs for him, is palpable. What soul! Alchemy squared.

Faldo had the same reaction to Preston, while watching the doc, that I did, and he had a Preston in his own life. “When Fanny came aboard,” he said, referring to his longtime caddie, Fanny Sunesson. “She started with me in 1990, I won two majors and nearly won a third.” They won the Masters that year, and the Open at the Old Course, and finished one shot out of the Hale Irwin-Mike Donald playoff at the U.S. Open at Medinah. “She was a lift.”

Back to that driving-range question: Were there days that Faldo came to the range, sometimes with Leadbetter, his longtime coach, intent on fixing something, improving something, trying something? You know, as the Beatles were doing in “Get Back.”

Yes.

“Every idea was a good idea,” Faldo said, describing his take on the Beatles in the documentary but also some of his own practice sessions. “Every idea was worth pursuing.”

As the Beatles would gather in the recording studio to see how their songs-in-progress sounded, Faldo would go to videotape and see what his swing-in-progress looked like.

“It’s technical, it’s visual, it’s science, it’s numbers — but in the end, you turn it into feel,” Faldo said.

Well, there’s the word of the moment, hour, the day, the week, the year. This year. Any year. Feel.

For whatever reason, no song in “Get Back” moved me more than “I’ve Got a Feeling,” as the Beatles played it on the rooftop of the Apple Records building on Savile Row, in London. McCartney, singing lead, wearing a shirt with French cuffs, on a weekday afternoon concert, on a cold January afternoon, dancing like a boy, smiling one moment, screaming the next, taking everything in, most especially his old mate, John Lennon.

I’ve got a feeling.

A feeling I can’t hide.

Oh yeah.

OH YEAH.

You can sense the love. His memory. Their past, their present, their future.

What is life without I’ve got a feeling?

The Beatles’ famous rooftop recording in 1969.

Tiger will sometimes work on his feels. Faldo knows it at a level you and I could not. One swing for a 173-yard 6-iron, another one for 175. One “feel” for a cut, open-face, three-finger 137-yard 7-iron into a hook wind. You’ll use it once and never again, unless you do. It’s in the memory bank. But we have feels all our own.

In the movie, McCartney is wildly enthusiastic for “Maxwell Silver’s Hammer.” Everybody else can’t stand it — you can see it on their faces — but they play it just the same. (Well, Lennon doesn’t. But he doesn’t walk out, either.) The things we do to preserve another person’s mood or well-being or feeling. There’s your feeling, and how you impact somebody else’s. Life’s balancing act.

Besides, when you’re making music as a Beatle, is playing on one “Maxwell Silver’s Hammer” clunker such a high price to pay? It’s like the tee shot on the 11th hole at Augusta National. Nobody is going to say, “This is the greatest shot in golf!” It’s a ridiculous shot, actually. But you’re playing Augusta National, so you’ve got that going for you. It’s all good. How you feeling? Pretty, pretty good.

You may have had this feeling, that the golf club in your hand or the surfboard under your feet or the bike that you’re riding, is working in tandem with you. Talk about a feeling. (Needless to say, there are private applications here that don’t involve inanimate objects.) Golf with a driver in hand is one thing. But golf with a wedge in hand is something else entirely. Open it, shut it. Take it back this far, take it back that far. There’s your feeling.

Sir Nick told me about a 3-wood he hit as a 15-year-old one day off the first tee at the Welwyn Garden City Golf Club, the course he first played as a kid, as he moved from swimming and cycling to golf. It was the first shot he ever flushed. Pure in every way. He can recall the feeling to this day. He asked me if I could recount a shot along the same lines. I can.

There’s a certain feeling of sorrow, watching “Get Back.” Lennon’s murder in 1980. I was in a basement reading room in a university library when I heard the news. Another student stood, announcing the horror with a trembling and angry voice. Most of us filed out of the library as one and many of us held up lighters or matchbooks, little yellow flames against the night and the pain. Lennon was 40. Billy Preston’s years of heartache before his death, at 59. George Harrison died at 58, from lung cancer. Linda McCartney died at 56, from breast and liver cancer. In the doc, they’re all so young.

Faldo knows the feeling, as we all do. He recalls seeing a photo of Elton John and Lennon together, in Elton’s home, in a room without another nod to a life in music. Just Elton and his hero. Faldo has a favorite photo of he and Seve together, circa 1976, at the Irish Open. They were kids, not even 20. Seve was 54 when he died, from brain cancer.

What a month the four lads and their crowd had, in January 1969. They must have had many other good days and weeks and months and years. But that month was a gift to all of us, or those of us drawn to the music they made.

I think, somewhere in all of this — in the magic of the Beatles, in that rooftop concert, in their playing of “I’ve Got a Feeling” — is the magic of golf, too. That feeling of the round, the ground underfoot, the club in your hand, the camaraderie of playing with your mates, the private joy of playing alone. The sun on your neck, the wind on your cheek — whatever it may be, there’s a magic in it. There’s a magic in it planted so deep it settles in a place where numbers don’t reach (but notes do).

Golf is all about numbers, on one level. That’s why it’s so fair. The number is the number, if you all play by the same rules. But then there’s another level of the game, and that’s golf’s subjective side. That’s the game with a shelf-life of forever. Faldo’s 3-wood, out of his bag and into his hand, the shot pured. McCartney walking across a neighborhood golf course in Liverpool, off to John’s aunt’s house, looking to make some music. A harmonica. A piano. A bass. A guitar. A coffee tin for a drum. The instruments of the game. Love me do forever.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com