At the age of 11, Tom Watson learned these five fundamentals — and he’s followed them ever since.

Getty Images

Golf instruction is ever-evolving, but the best advice stands the test of time. In GOLF.com’s new series, Timeless Tips, we’re highlighting some of the greatest advice teachers and players have dispensed in the pages of GOLF Magazine. This week, we look back on the five basics of the golf swing according to Tom Watson from our January 1980 issue. For unlimited access to the full GOLF Magazine digital archive, join InsideGOLF today; you’ll enjoy $140 of value for only $39.99/year.

Every golfer was a beginner at one point. Even those who’ve won major championships.

Take Tom Watson, for example. Back before he ever dreamed of winning a major (let alone eight), he was just another Kansas City kid working to hone his golf game. Hard as it is to believe now, when Watson was 11, his handicap was 17.

His inability to whittle down his handicap wasn’t a result of his natural ability, though. He had plenty of that. Instead, the thing holding him back was his inconsistent fundamentals. That’s when he teamed up with Kansas City Country Club head pro Stan Thirsk to iron out those basics.

In this week’s edition of Timeless Tips, we look back at an article from the January 1980 issue of GOLF Magazine, penned by Thirsk, that outlined Watson’s five basic fundamentals. And while they likely won’t lead you to win eight major titles (although we’d love if they did!), they might help to take your game to the next level.

Tom Watson’s 5 golf-swing basics

Brisk, compact, efficient. Those are words that are commonly used to describe the golf swing of Tom Watson.

It wasn’t always that way.

I still remember the day Tommy walked into my junior clinic at the Kansas City Country Club, a small freckle-faced 11-year-old with a handicap of 17. But I knew immediately he was a cut above the rest. He could knock the ball 200 yards and chip and putt the eyes out of a grasshopper. Yet he had serious problems with his grip, his setup and his swing.

Tommy and I worked together to correct those faults, one by one, as I taught him my five basics of golf: grip, posture, alignment, rhythm and balance.

It took several years and lots of hard practice, but Tommy was never afraid of work. In one year he got his handicap down to 10; a year later to seven, the year after that to four. By age 17 he was a scratch player and the winner of the Missouri State Amateur. The rest, as they say, is history.

Certainly, I was not Tommy’s only teacher. He first learned to play the game, and more importantly, to love it, from his father, Ray, a top amateur in the Kansas City area. During college, he got lots of help from Art Bell, the professional at Pebble Beach. More recently he has refined his game with the help of Byron Nelson. But Tommy and I still confer whenever he’s in Kansas City, and our conversation always centers on the same five basics I taught him nearly 20 years ago. They’re his basics now, and with this article I’d like to make them yours.

1. Grip

Tommy came to me with a grip that was far too strong. He had rotated his left hand so far to the right that almost four knuckles were visible. To make things worse, he held the club so tightly that his forearms rippled when he took his grip.

Those two errors combined to force Tommy into a pattern of pushed shots and hooks. Normally, he couldn’t get the club squared up in time for impact — thus the pushes. When he did square it up, he did so too suddenly and violently, causing the hooks.

We made two corrections. First, I got him to take more of a square grip, with the hands rotated back toward the left, so that only about two and a half knuckles showed on the left hand. This grip is the safest one for most golfers. I also had him loosen his stranglehold, so that he held the club with just enough pressure to control it. This freed the tension in his arms and gave him a smoother, more flowing swing.

2. Alignment

At age 11, Tommy had a completely open stance. His foot line, hip line and shoulder line all pointed way left of the target. He also played the ball too far forward in his stance — opposite his left toe. This unorthodox setup gave him all sorts of problems.

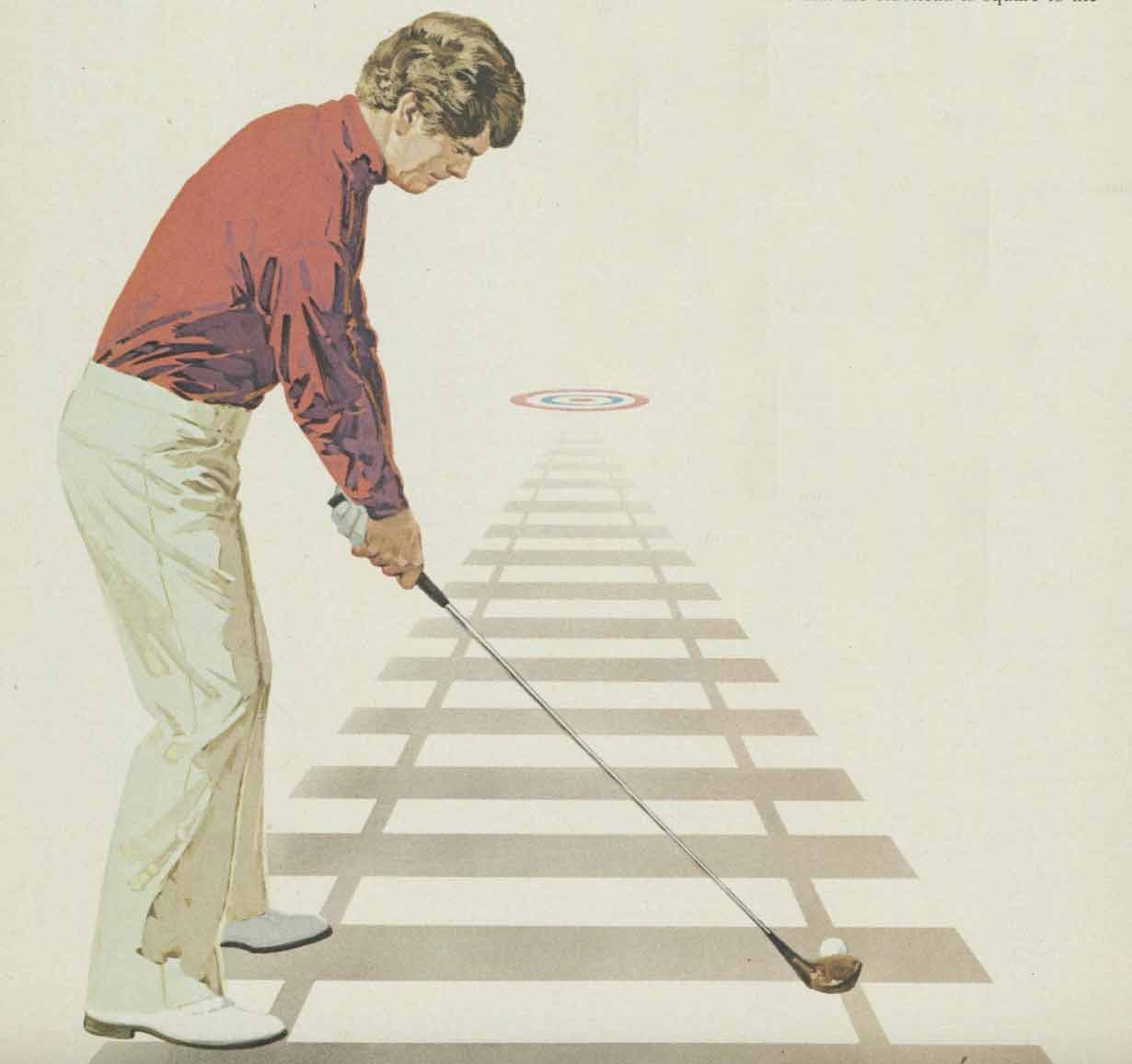

The first correction we made was to move the ball back — about three inches — to a point just opposite the left heel. We then squared up his stance, so that everything was on the “‘railroad tracks.’’ I told Tommy to imagine the ball was resting on the outside rail and he was standing on the inside rail.

GOLF Magazine

Tommy was, and is, a stubborn fellow, and it took a while for him to adopt this strange, new address position. He’d use it for a while and then, like most of us, he’d hit a few bad shots and drift back to the old way. Eventually, it sank in, and today he adheres to that position with the same vehemence that first caused him to resist it.

3. Posture

When 11-year-old Tommy stood up to the ball, he flexed his knees too much and kept his back extremely straight, which forced him to make an extremely flat swing, once again encouraging the pushed and hooked shots.

So, step three of our improvement program was to fix his posture. I got him to take a little of the bend out of his knees and to put it into his waist. His present posture reflects that early change — a slight flex in the knees and enough upper body tilt to allow his hands to hang naturally from the shoulders to the grip of the club. This posture encourages the upright, high-handed swing that is his trademark. It also sets up the proper inside-to-square- at-impact-to-inside clubhead path, while making full use of the amount of time that the clubhead is square to the target.

4. Rhythm

Once we had straightened out the mechanics of his setup, we Started concentrating on Tommy’s biggest problem his rhythm. As a youngster, he had a bad but common habit: He took the club back too slowly. Yes, too slowly. He had read and heard about the importance of a slow swing and he exaggerated that point as he took the club back.

By making a super-slow takeaway, he forced himself to speed up at the top of the swing. Like many golfers, he would say to himself, ‘‘Gee, I’m swinging so slowly I’ll never get any distance, I’d better speed up the club.’’ So he did — at the worst possible time.

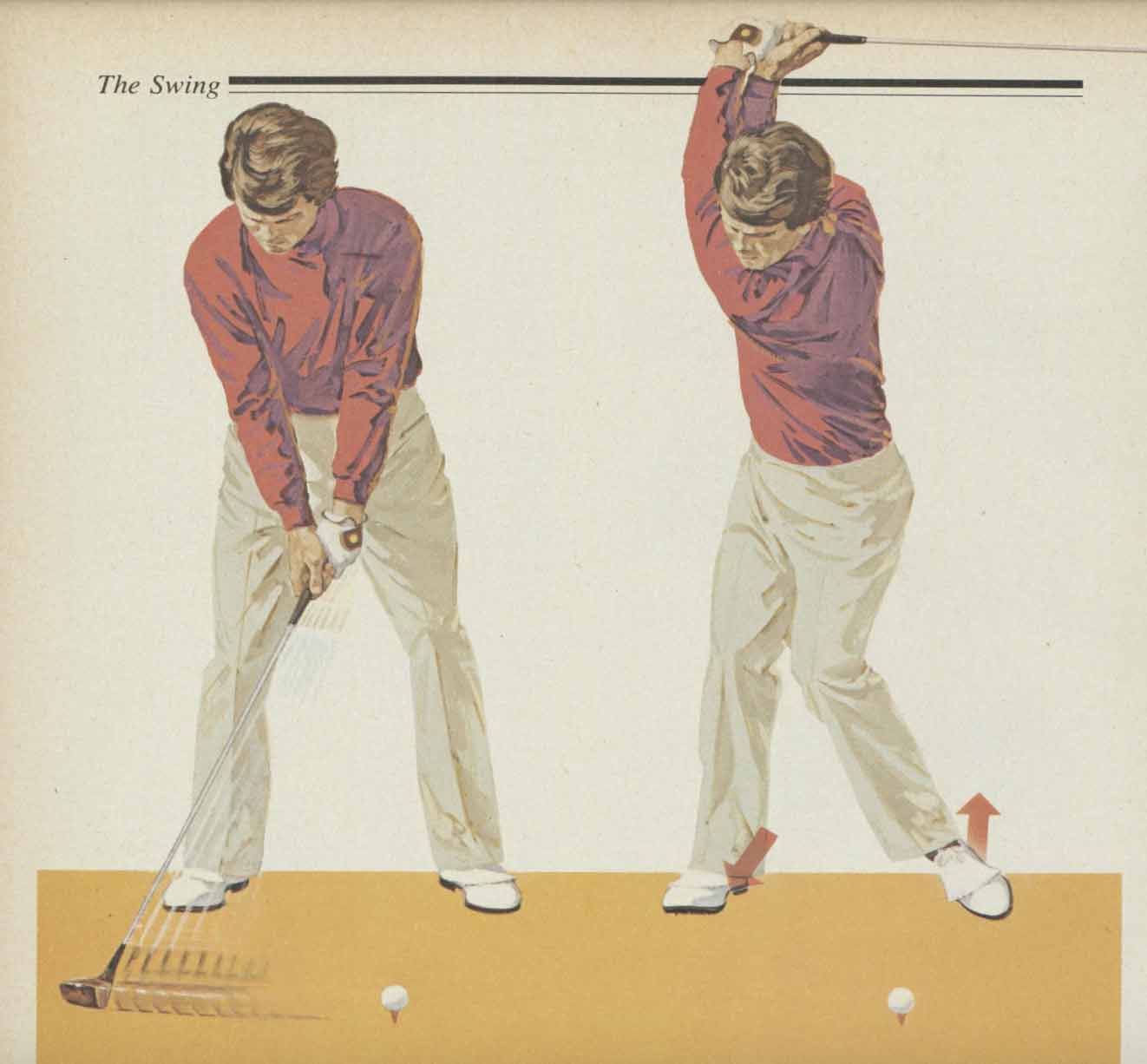

GOLF Magazine

I permitted him to take the club back as quickly as he wanted, as long as he slowed down at the top of his swing and made a smooth, unhurried transition from the backswing to the downswing. I also taught him the importance of a one-piece takeaway, where the shoulders, arms hands and club all move away from the ball at the same time. This eliminates the tendency to flip the club too quickly — it’s a takeaway, not a pick-up. The lower body follows this lead and then, as the arm swing slows at the top, the lower body takes over leadership of the swing for the move to impact. By the time the ball is hit, the arms, shoulders, hands and clubhead have caught up with the lower body, and every part of the body arrives at impact at once, in a smooth application of maximum power.

Together, we worked on the well-paced, one-piece takeaway and emphasized the importance of an unhurried transition at the top, from the backswing to the downswing. Tommy still practices those keys. Rhythm, in fact, is now his main area of concentration.

5. Balance

Balance is important both at address and during the swing. Tommy’s balance was always good. However, we did work on several keys to develop his consistency.

First, I taught him to play golf on the insides of his feet. At address we got his weight equally distributed on the insides of his feet. At the top of the backswing we got most of his weight on the inside-middle of the right foot with the remainder on the toe of the left foot. I encouraged him to make this weight shift by getting him to raise his left heel during the backswing. This move, which he still makes, not only encourages proper top-of-the swing balance, it facilitates a large hip turn and a wide swing arc for plenty of distance. It’s especially good for older and thickly-built golfers.

The left foot also is the key to balance on the down- swing. I got Tommy to think of starting his downswing by. returning his left heel to the ground. This move triggers the release of the rest of his body. I also told him that at impact he should strive for the same feeling of balance he had at address — with the weight equally distributed on the insides of his feet. Of course, that isn’t actually the case. At impact the lower body weight has already shifted to the left and by the finish, the weight is for the first time on the outside of his left foot. But by trying for this flat- footed address feeling at impact, he avoids the big errors of spinning out or reverse pivoting. His weight shift is close to perfect.

There they are, the five keys: grip, alignment, posture, rhythm and balance. Very simple, and yet they encompass all you need to know. They have worked for Tommy Watson, and they can work for you, too.