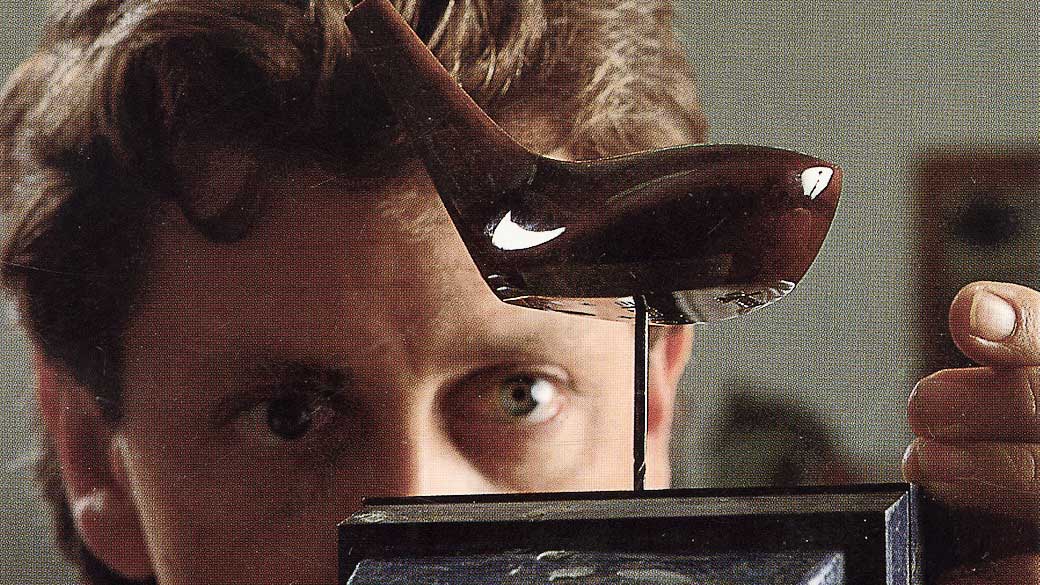

She was in an aquarium. They all were. Her brothers and sisters, all submerged in 10-gallon mixtures of boiled linseed oil and turpentine. God, the smell was terrible. Sitting and soaking. Waiting to float. That’s how you knew. This one, this perfect 208-gram block of persimmon wood, was in there for days. Weeks. Months. Every time she was removed to get weight-checked, she wasn’t quite there yet, so back into the bath she went. Finally, after a few months, it was time.

You could tell, right from the get-go, this one was different. She was more fickle than most. A little more temperamental. She took longer during the drying process, too. Sheesh, that was a pain — there were deadlines to meet, you know? — but finally the time had come. By this point, she had acquired a name: Christine. Named her after that Stephen King novel where a ’58 Plymouth Fury has a mind of its own and a little murderous streak to boot. He carried Christine out to the side of the workshop, opened the trunk of his Datsun B210 hatchback and placed her down to cure under the hot Texas sun.

Clubs of character is how Dave Wood always believed golf clubs should be made, but hot damn, the good Lord never created a block of persimmon like Christine.

Fred Clark

“It was perfect in every way,” Wood recalled. “But it had a little bit of Elvira to it. All the markings were different. This was a block of wood that had a hard heart to it.”

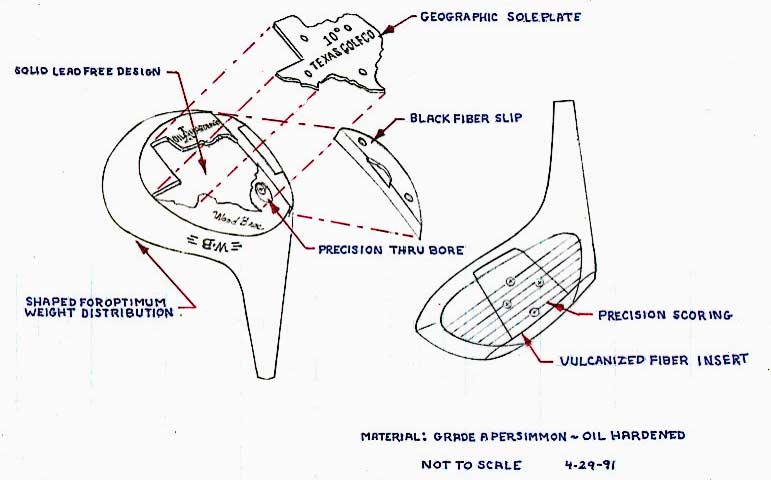

By the time Wood had polished her up, screwed on the identifying sole plate at the bottom — the one with the big, shiny silver silhouette of Texas, with “TEXAS GOLF CO.” across the middle of it — affixed her to a 43 ½-inch Dynamic Gold X100 steel shaft, adjusted her to a 10-degree loft, a D-3 swing weight, and gripped her up, she looked like the dozens of prototypes that he would roll up to PGA Tour events with on a weekly basis. She was ready in time for his trip to the 1986 Los Angeles Open at Riviera Country Club, where he was scheduled to meet with several the world’s best players. Among them, was a potential new client: a 28-year-old mild-mannered German, who was the reigning Masters champion.

Bernhard Langer needed a new driver and wanted Dave Wood to make him one. As he tested a few different models on the range, Langer liked some of them, but the connection wasn’t quite there.

Then he saw Christine.

“It had a nice pear shape,” Langer recalled the other day. “It seemed solid, it would go a good distance when I hit it. I was always interested in performance, but these didn’t just perform well, they looked good, too.”

Langer took her, teed it up and began swinging away. His caddie, Peter Coleman, stood at the other end of the range at Riviera, signaling with his arms which way the ball would move. (Think prehistoric Trackman.) Wood stood a few feet back and smiled, as Langer drilled ball after ball perfectly. He had made clubs for some of the up-and-coming players on Tour for a few years, but bagging a current major champion would be a coup for his growing outfit. He knew what was coming next.

“Bernhard took it right there,” Wood said. “He wanted to keep it. And that was kind of the beginning of that. That’s how that relationship began with Wood Brothers.”

Dave Wood

Bernhard Langer and Wood Brothers Golf. Hard to find a more dynamic pairing in golf through the late 1980s and early 1990s. Langer would take Christine and then her descendants all over the world, winning more than a dozen times, playing in three Ryder Cups and, in 1986, becoming the first player to be ranked No. 1 in the new Official World Golf Rankings. Dave Wood and his small club-making business soon exploded alongside Langer’s success. By the end of the 1980s, the best players in the world were playing his handcrafted persimmon woods: Seve Ballesteros, Greg Norman, Ben Crenshaw, Steve Elkington, Bob Tway, Hal Sutton, Jeff Maggert and Jeff Sluman. They would win PGA Tour events and major championships, and achieve career highs.

And each time, more orders would pour in for Wood.

The business grew. He added employees, staff, executives. Soon, Japanese partners entered the mix. He was global now. Had to fly around the world, including numerous trips to Nagoya.

It was there, in 1993, that he watched the final round of the Masters. Langer would pull away from the field to win, using his Wood Brothers Texan persimmon driver — making him the last player to win a major championship using a wooden driver. Halfway around the world, Wood beamed with pride in the early morning as he watched Langer slip on his second green jacket.

He was at the height of his sport.

The peak of his profession.

What nobody knew, was that Dave Wood would soon walk away from it all.

+++

Camellia.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing on the tee box of the 10th hole on Sunday afternoon at the Masters, with a one-shot lead over Dan Forsman and two shots over Chip Beck. Langer is wearing a yellow golf shirt, olive pants, white visor, staring down the hole where the “tournament really begins.”

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, on this resplendent Easter afternoon, and swings away. The ball flight is textbook: arrow straight, with a little fade at the end.

It finds the perfect spot on the left side of the fairway.

“I was driving the ball pretty good,” Langer recalled. “Augusta for me, in those days, had the big fairways. So, I never thought it was a hard driving course, except for a couple of holes like 10.”

THRU 9

Langer -9

Forsman -8

Beck -7

+++

Soup. Why did he order soup?

It was 1982. Dave Wood had been summoned to Champions Golf Club in Houston at the behest of Jackie Burke and Jimmy Demaret. Golf royalty. Texas royalty. Four green jackets between them. Wood had done some small club work for Burke, but to get an audience with him and Jimmy? What was this about? They were seated in the dining room of the clubhouse overlooking the course, the crisp white linens, shiny silverware, napkin rings. Probably the most formal meal Wood had ever been to. He was so nervous that he couldn’t really think, so he panicked and ordered…soup?

Burke cut right to the chase.

“All of the good clubmakers are dead,” Burke said from across the table. “Nobody makes ‘em any good anymore. You don’t manufacture a golf club, you build it. With your hands.”

OK …

“A golf club is an instrument, not a piece of equipment,” Burke continued. “I’ve seen some of the work that you do. You have a skill for this. I know you’re also trying to make it out there professionally, but I’m telling you right now, Dave – this is your destiny.”

Wood couldn’t swallow. He had come for lunch, he presumed, as a thank you or something for the work he’d done, and now he was supposed to throw away his dreams of making it to the PGA Tour in order to…build golf clubs?

As he listened to Burke talk about the need for serious golfers — ones with professional aspirations, legendary aspirations — to have drivers that were handmade and the absence of that skillset as golf became more modernized, it began to strike a chord with him. Wood’s small club repair gig that he did on the side to supplement his professional dreams allowed him to see what equipment players were using. Many of the top players in the area, whether it was professional, amateur or collegiate, used old equipment that was made and designed before they were born. Only the top 1 percent of professional golfers — the Palmers, the Nicklaus’, the Players — had equipment that was designed for them.

Dave Wood

Wood had been toying with getting onto another career path, so…maybe this could work? He took a shot and began asking Burke what he wanted and looked for in a driver. Wood figured if Burke thought he could make a career of this, who better than a Masters champion to be his first customer?

Over the soup he never finished, Wood talked with Burke about weight, shape, shot type. Demaret then walked him through the painstakingly long oil-hardening process, and how getting a solid block of wood that was the perfect weight — between a 205- to 215-gram starting weight — was so important to the final finished product. Wood started to think that this seemed doable enough.

“I was already living in a world of specifications,” Wood said. “My own, players I worked with whose clubs I worked on. Balance, weights, where you wanted the flex point on the shaft — all those things. So, I started to think this wasn’t much different than the work I had already been doing.”

Burke’s final piece of advice was a necessary one.

In all his years working on clubs, Wood had never carved a driver head from a block of wood. He asked the great man, How, exactly, do you go about shaping it into its final form?

Burke smiled.

“There was this old member at Champions, who carved ducks as a hobby,” Wood remembered. “One day Burke had asked him, ‘These things are so life-like, how do you do it?’ And the man told him, ‘It’s simple, you carve away anything that’s not a duck.’”

Wood laughs thinking of Burke’s counsel.

“He never gave me any specifications for his driver,” Wood said. “So, I went and got a block of wood and carved away anything that wasn’t a golf club.”

Wood Brothers Golf was born.

+++

White Dogwood.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing on the tee box of the 11th hole on Sunday afternoon at the Masters, still with a one-shot lead over Dan Forsman and two shots over Chip Beck. Langer is about to begin the stretch of holes that define how the tournament is won or lost: Amen Corner.

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, stares down the hole on this resplendent Easter afternoon, and swings away. The swing is loose, the ball flight wayward: a push to the right.

It lands softly with a perfect line into the green.

“I knew that I wouldn’t win the tournament unless I played aggressively,” Langer would tell Sports Illustrated afterward. “Nobody was going to give it to me.”

THRU 10

Langer -9

Forsman -8

Beck -7

+++

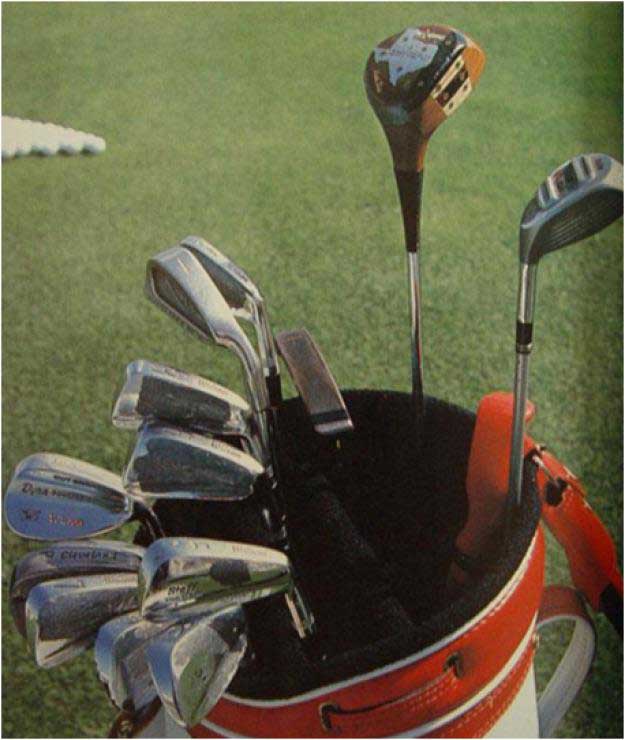

When you walked into the front door at 101 East Main Street, you knew exactly what awaited you inside. The reception desk was smack in the middle of the room — Dave’s sister, Sue, would be behind it answering phones, taking orders that sort of stuff — and around the walls were a menagerie of golf club items: Old MacGregor woods, Ben Hogan irons, showcases with golf collectibles to peruse. A couple of chairs were scattered about.

This was the Texas Golf Company — part custom club outfit, part Elks Lodge.

Pink Floyd often blared from the backroom as Dave worked on clubs by hand. He was the artisan, founding the company on his own. Later, as more work came in, his younger brother Charlie, and then Don, would float in and out of the business, occasionally helping out. But when you walked in the door, you shouted to the back for Dave, and out he would come with your club in tow. He was the company.

“When people ask me about it, I tell them ‘Everything came together at once there,’” recalled Dr. John Kendall, one of the first Wood Brothers customers in the late 1970s. “It was kind of like a magical time.”

Kendall was a low-handicap member at Sugar Creek Golf Club in Sugar Land, just southwest of Houston. A director of R&D for Riviana Foods in the city, he would routinely make the 20-mile drive up I-69 at lunchtime to Humble to spend time in the shop. Not just because he would begin enlisting Dave for custom orders, but because you just never knew who you would run into inside. Everyone from John Mahaffey and Andy Bean to T. Boone Pickens and Darrel Royal to Willie Nelson (yes, seriously) and George Strait.

(That’s really where the “Wood Brothers” name would actually come from: Not from Dave’s family members — some of whom would work for him in limited capacities over the years — but from the close-knit relationships of the individuals who frequented the place. “Wood Brothers” wasn’t formally established as an official brand until 1988, operating under Texas Golf Company, until the company disbanded.)

Despite its sprawling scale, Houston is a relatively tight-knit golf community. As Wood began to put the advice of Burke and Demaret into action, word began spreading about his craftsmanship. The University of Houston golf team were the first true converts, creating a pipeline of sorts for business. Keith Fergus and Ed Fiori were the first in the late 1970s, going to Dave for repair and small custom work. By 1982, another future star — Steve Elkington — began hanging around the shop so much, Dave would put him to work one summer.

“You’d have collectors, afficionados, great amateur players, Tour players, mini-tour players, club pros that would hang out,” Dave Wood said. “Everyone was very knowledgeable about golf equipment and history. But the top collegiate players really helped us get some traction, because these guys would use our early products as amateurs, come up, make it big, and then everyone would want to know what they were playing.”

Within a year after his lunch at Champions with Burke and Demaret, Wood began to see the vision they saw. He began to push harder to accelerate the timeline to develop a persimmon model that a PGA Tour player could utilize week-in and week-out. The prototypes they developed were good, strong models for amateur players and top collegiate ones, but to capture the upper echelon of golf, Dave needed a driver that was perfect.

Dave Wood

Late into the night, the lights would be on in the back room in the shop on Main Street, right next to the old Union Pacific railroad tracks. A Texas golf nut tinkering and toying, all in the hopes of finally cracking the code that would let him unlock the next step in the journey. It would be a calling card for Dave throughout his career — his nickname would become “The Count” — the late hours he spent obsessing over the details that would make his clubs great.

He circled the 1984 U.S. Open at Winged Foot as the debut site to bring it to the masses. He knew they were close. But nailing the finishing weight of 200 grams, took time.

“I had it in my mind,” Wood recalls. “I had it in my mind before I even made it. Other ingredients had to come together — and that took time — finding that perfect, solid block with the exact gram weight. Jimmy Demaret gave me the recipe, but the ingredients took time. It’s a natural resource, wood is. It comes in different weights, different densities. So, it was a very careful process. My world was all about balance.”

By the end of 1983, it was finished: He named it “The Texan.”

+++

Azalea.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing on the tee box of the 13th hole on Sunday afternoon at the Masters, with a one-shot lead over Chip Beck. Dan Forsman is gone now. Put two in the drink at the 12th for a quad. Langer is now stepping up to the risk-reward par-5 that can seal the deal or open the door.

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, stares down straight into the dogleg on this resplendent Easter late-afternoon, and swings away. The ball flight returns to textbook: a perfect fade to match the shape of the hole.

It lands softly on the low, left side of the fairway.

“Going in Amen Corner, I missed a little putt on 12 that just went right,” Beck would recall. “I thought, ‘Oh man, that was a missed opportunity to get one’, because he made par.”

THRU 12

Langer -9

Beck -7

+++

When Dave Wood arrived at Winged Foot for the U.S. Open in 1984, change was happening right in front of him. For the last handful of years, golf club manufacturers had begun introducing a new product to the game: metal drivers. They promised more power, more control, more distance. A fad, many thought.

The first one showed up on the PGA Tour in 1979, and then two years later — right in Dave’s backyard — it would have its breakthrough moment at the Michelob-Houston Open, when Ron Streck became the first golfer to win a sanctioned event with a metal driver. (Purists still scoff because the event was shortened to 54 holes.) While the upper crust of players looked down their noses at the clubs, they began to gain traction. Soon, players spoke about the distance advantages and how that helped them get over the awful tinny sound the clubs made at impact.

“I remember going to the driving range in Fayetteville, N.C. and L.B. Floyd, Ray’s dad, had these metal woods,” said Chip Beck, a four-time winner on the PGA Tour, who transitioned to metal woods in the late 1980s. “And they went farther than any club at the driving range. I knew they were hot, but they were never really available early on.”

The sight on the range at Winged Foot was jarring: Some of the most strident persimmon stalwarts were showing up with metal woods in their bags. Dave Wood, though, remained undaunted. He had worked too long, too hard, to abandon the quest now.

There was an element of perfecting a dinosaur.

But it was a dinosaur that was still in high demand.

Players of skill were still clamoring for a driver that placed a premium on accuracy, and the ability to shape a shot. Because of the precision nature that went into creating every driver — and the growing list of top players from the Houston area espousing their excellence — the business was booming, even as metal woods crept into the market.

As Dave Wood took on more and more business, the simple grounded nature of his company’s origins began to become more complicated.

Things had become so big that Dave expanded beyond the shop in Humble, and would add more than 100 employees by the start of the next decade. His weeks were spent travelling to meet with ad executives, to meet with marketing executives, back to Texas, then off to a tour event, then back home for more club work, then back out on the road.

Life would become even more frenetic when in 1987, he was wooed and eventually entered into a partnership with Japanese textile company, Nihon Hymo. The company’s chairman, Keitaro Takagi, flew to Humble to meet with Wood for days to get a sense of how his operation ran. Then he flew Dave and his wife Laura to Nagoya to seal the deal: Nihon Hymo would be the official Japanese distributor for Wood Brothers Golf. A year later, they created a joint venture, and Nihon Hymo gave Wood Brothers an infusion of capital.

Dave Wood

By the end of the 1980s, Wood Brothers was at the top of the golf world.

The price was the Japanese corporation getting 48 percent share of the company.

“I think by that time, for me, it just started to consume my life,” Dave admits now.

+++

Firethorn.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing on the tee box of the 15th hole on Sunday afternoon at the Masters. He has a three-shot lead over Chip Beck. Somehow rolled it in for eagle at No. 13. Langer is now facing the hole where Gene Sarazen made double-eagle and where eight years earlier Curtis Strange found the water to give Langer his first green jacket.

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, stares into the 500-yard par-5 and the setting sun on this resplendent Easter afternoon, and swings away. The swing is a little across his body, but the result works just fine.

It lands softly on right side of the fairway.

“I was trying to figure out how to make three birdies and get into a playoff,” Beck remembered 30 years later. “I knew how well I was playing, and I knew what the opportunities were.”

THRU 14

Langer -11

Beck -8

+++

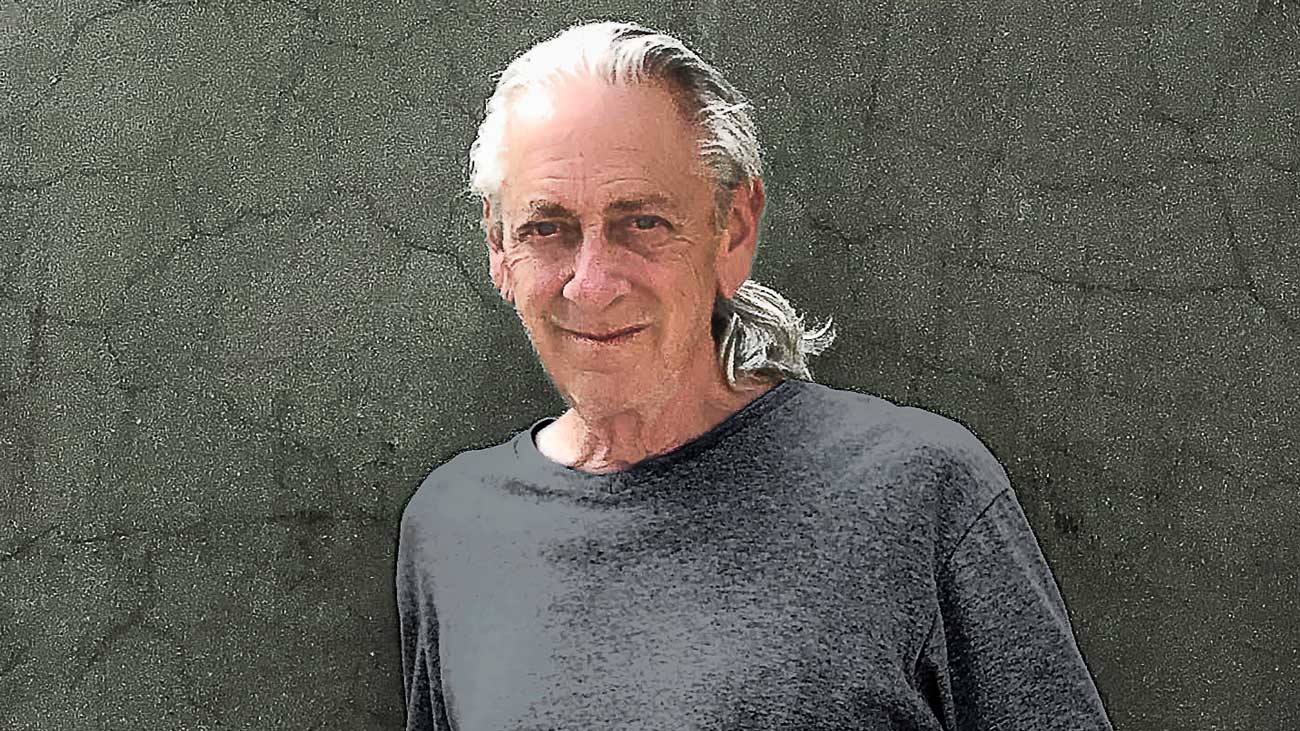

“I was a Disneyland dad.”

Even 30 years later, there is a pain in Dave Wood’s voice as he admits the truth out loud to himself. He had built Wood Brothers from a club-repair hobby to the most sought-after custom clubmaker in the game in just more than a decade. He made friends all over the world, the sport. Built clubs for Vice Presidents, Secretaries of State, Prime Ministers, CEOs, some of the most powerful people in the world. He had it all.

Except at home.

His children, Sally and Nick, were entering middle school when dad went from a guy with a golf club-making shop to an international sporting goods maven. Went from being home and taking them to games, practices, school events to calling from far-flung outposts around the world. Home for a day, gone for four. Back for two, gone for six.

The business was becoming a monster that needed to be fed at all times: more ads, more slogans, new products, new pros playing the products. With the Japanese involved, they pushed to expand Wood Brothers into other areas of the golf business — they wanted bags, gloves, hats. Anything to stick a “WB” on to sell to the global markets.

Dave was in deep.

He felt the ownership of what he built slipping away. He felt his family slipping away. He felt himself slipping away.

Then, it did.

“Almost overnight, I became a single parent,” he says solemnly. “My world changed.”

Dave prefers to keep the details private, but around the time of the 1993 Masters, he phoned home from the road. The housekeeper answered. He asked where his wife was. Housekeeper said she was gone. Took her belongings and left. Dave was stunned. There had been problems of late, but he chalked it up to the job. But when he arrived home, he immediately knew what he had to do next.

He had to become Dad once again.

He also began to wonder whether staying at Wood Brothers — in its current form, with its current demands — was a tenable situation. Yes, he was living a nice, comfortable life, but what would that end up costing him? What would be the next domino to fall? His marriage? His family? His friends? Wood didn’t want to wait around and find out.

When he would leave, he didn’t yet know — or even figure out for more than a year — but that moment, when he walked in the door and hugged his children and let them know that Daddy wasn’t going anywhere, was the planting of the seed.

“My kids needed me,” Wood said. “I didn’t walk away right then and there — I hung in there — but everything changed. I knew that I couldn’t keep things the way they were.”

He would stay on until early 1996, but mostly phased himself out of the company he created and built from scratch. His brother, Charlie took over a good amount of the club-making work — most of which was being manufactured now — but once Dave stopped being the engine, the Wood Brothers aura quickly faded. Pros stopped calling. Orders slowed. The shop on Main Street saw fewer and fewer friends stop by.

Then, at age 40, Dave Wood walked away from Wood Brothers for good.

+++

Nandina.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing on the tee box of the 17th hole at the Masters. He’s the owner of a five-shot lead over Chip Beck. Tournament is basically his now, after Beck bafflingly laid up on No. 15 and made par, then followed it up with a bogey on 16. The sun is beginning to set alongside any hopes of a collapse from the German.

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, stares down the tricky short par-4 with the Eisenhower Tree on the left. As a resplendent Easter afternoon gives way to the eve, he swings away. The swing is once again as he has practiced it countless times before: consistent, effortless.

It lands and rolls out on right side of the fairway.

“He wasn’t doing anything extraordinary,” Beck said. “It wasn’t like he was out-driving me or hit it any different than I’d ever seen him. I’d beaten him in tournaments before. But not that day.”

THRU 16

Langer -12

Beck -7

+++

Fred Clark can still remember the exact date: Nov. 10, 2009.

His wife was a few months pregnant, and he once again found himself on eBay late at night perusing through classic golf clubs for sale, when he stumbled on a listing, that he was sure was a con. It was a pristine Wood Brothers Texan. Mint condition. Clark couldn’t believe his luck. He had foolishly given away his first and only Wood Brothers driver a few years back and had been searching for another for a while. But a Texan? In this good of a condition?

He clicked on the page and found a description that almost read as the club’s biography.

“I’m reading this whole thing, and it’s so detailed, I couldn’t believe it,” Clark recalls with a laugh. “And I get to the bottom of it, and it says, ‘From the collection of Dave Wood.’”

Nah. Couldn’t be.

Could it?

It was. Nearly 15 years after leaving Wood Brothers, Dave Wood was preparing for his life’s next chapter. He had just wrapped up a nearly eight-year run working for MacGregor Golf and decided it was time to pursue his true passion: art. He had opened a studio in downtown Houston, split time between Texas and Oregon, but had decided it was time to part with the dozens and dozens of Wood Brothers clubs in his possession.

Clark — a software sales executive who lives in Salem, Mass. — is one of hundreds of devoted Wood Brothers fanatics who have kept the company’s name alive even after the company shuttered. Because the clubs were designed custom for low-handicap players, they remain rare and hard-to-find on the collector’s market. Often they come from the hands of a Tour pro or accomplished amateur, and when they do pop up for sale on eBay, easily fetch north of $500.

“They were very hard to get back then,” said David Bass, a persimmon club restoration expert. “You just didn’t have an average golfer walking around with one. And you hardly ever see one that’s been restored. That’s because they’ve held up over the years. I very rarely see one because the things just don’t beat up.”

I get to the bottom of it, and it says, ‘From the collection of Dave Wood.’

There are Facebook groups devoted to Wood Brothers, Instagram pages and dozens of threads on GolfWRX.com with collectors and enthusiasts sharing knowledge, history and more about their persimmons. It’s given Dave Wood a second burst of celebrity within the golf world. Wood Brothers has regained traction even as modern drivers promise speed and distance combinations once unimaginable.

But the persimmon drivers — particularly from Wood Brothers — carry equal parts nostalgia and practicality. You can pick one up out of an attic or garage or from another collector and put it into play immediately. The oil-hardening process passed down to Dave from Jimmy Demaret is a big reason why, but also there was minimal invasion of the club’s heads during the building process. Screws were smaller, thinner. There were no artificial materials.

So, imagine Clark’s surprise when, a few weeks after buying the driver from Wood, another email popped into his inbox:

Fred – you seem very anxious to build your collection. Would you like buy the Bernhard Langer driver from me? It was his tour demo.

No.

Yes.

It was Christine.

Wood had retrieved her from Langer around 1989, at the PGA Merchandise Show in Orlando, after making him another set of drivers. She sat in Wood’s storage for more than 20 years until he began cleaning out. Clark didn’t hesitate and has even taken her for a test spin once or twice. He was immediately the envy of every Wood Brothers collector, even receiving offers from around the globe to buy it.

“I would never get rid of it,” Clark beams.

It’s a prized possession. Which is why, two years after he bought it from Wood, Clark made an unusual request: He wondered if the man who made it would refinish the club and bring it back to its original luster. Wood happily obliged.

Clark shipped the driver out to him and when they initially talked about stain color and restoring it, Dave mentioned an idea for a “special stain.” Clark was intrigued but left it up to Wood to come up with the idea. A few days later, Clark received a surprising message: It was a picture of a scalpel and blood all over the clubhead.

“I’ll never forget it as long as I live,” Clark recalled. “I get an email back from Dave, that says that as he was refinishing the club, it was so special to him that he decided to add something to the stain so that he would be bonded with it.”

Clark pauses, and then laughs because it still sounds wild to say out loud.

“His blood.”

+++

Holly.

This is Bernhard Langer. Standing in the back of the tee box of the 18th hole at the Masters. He has a five-shot lead over Chip Beck. They’re getting Langer’s green jacket — the one from 1985 — out of the Champions Locker Room, and bringing it down to Butler Cabin for the TV cameras. A couple of shots left until the end. It’s been a perfect Easter Sunday for Langer, his favorite holy day.

He pulls out his Wood Brothers driver, the one that has lifted him to this point, for the final time on this day, as he tries to navigate his way home. With the setting sun at his back, and 465 yards in front of him, he takes what will be the final-ever swing with a persimmon wood by a winner at a major championship.

He lashes at the ball, squinting as he watches it come down out of the baby blue sky.

It takes three bounces and lands––

THRU 18

Langer -11

Beck -7

+++

Does it matter where that ball landed? Does it matter that if it took three bounces and landed in the front bunker near the elbow of the fairway on the 72nd hole? Does it matter if Langer would make a bogey there? Does it matter that once his ball landed, he turned to his right, handed his well-worn Wood Brothers Texan to his caddie, who put it back in the bag, only to never take it out again?

Does that matter?

Should it matter?

Dave Wood doesn’t think it does. He prefers to think of Langer and his ultimate creation — hand-in-hand, methodically bruising their way across the manicured grounds of Augusta National in the pounding sun on a beautiful Easter Sunday — showing the golfing world just how years of dedication, practice and endurance can triumph over modern technology. That’s the vision he has of Wood Brothers these days. He’ll think about it from time to time, when he goes out early on Tuesday or Thursday mornings with a couple of irons and wedges — Wood Brothers brand, of course — to hit balls in the warm air at Country Club de Chapala, a short drive from his home in Ajijic, in Central Mexico, just south of Guadalajara.

He moved there full-time during the pandemic. Loves it. Nestled up against Lake Chapala, he lives a life that seems like a fantasy. Walks along the cobblestone streets, or along the water. It’s the perfect place to have fully embraced his true artistic side. Now, he spends his days painting, drawing inspiration from the beauty around him.

Dave Wood

Every now and then, he’ll think back to the long nights grinding away with a newly cured persimmon head or putting the finishing touches on The Australian or traveling the world preaching the gospel of the game. He’ll think about the players he met, how he helped change and shape their careers — their legacies — and how they changed his life from a wannabe tour pro to the craftsman on call for the world’s best players.

“Apples don’t fall too far from their trees,” he said with a laugh. “As much as I love being a part of the art world and that community, I still love to go out and hit balls. Love to be out in the sunlight and the grass. Life here is so easy, so low stress. It’s the world of mañana.”

Tomorrow.

Once he knew the end was approaching with Wood Brothers, he invariably found himself thinking about the tomorrows to come.

That’s why shortly after Langer slipped on that green jacket for the second time, Wood began one final journey. After he returned home from Japan, he flipped on the lights in the back of the shop on Main Street in Humble — where the city slogan is “Where people make a difference” — and placed a perfectly weighted solid block of old-growth persimmon into the aquarium bath. He would check back on it every couple of weeks, in between he would begin sketching out the other aspect of his masterpiece.

Langer was a devout Christian, his success deeply rooted in his faith.

Wood always admired that about Langer, and immediately following the win at the Masters 30 years ago, Wood set on what would be his masterpiece: He meticulously copied Leonardo di Vinci’s “The Last Supper” by hand, stenciling it first while the block of wood readied itself. Once the clubhead was prepared and ready to be turned into a golf club, he began engraving the depiction of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles across the skirting of the driver head.

“I wanted to thank him in a very personal way,” Wood said. “To me, as an artist, it was a great ambitious project.”

The driver would be built with a 54-degree lie, slightly flat. Little bit open at address. Nominal face progression, with a 9-degree loft. It was designed to hit that piercing, launched trajectory that Langer was known for.

Wood began with Bartholomew, then on to James Minor, Andrew, Judas, Peter and John. Then came Jesus Christ — that was the one Dave felt the most pressure on, “It was pins and needles” — before finally moving to the other side of the table: Thomas, James Major, Philip, Matthew and Thaddeus. Finally, came Simon. There is a wicked irony in that. The most obscure Apostle, the one who was only identified as a zealot. Who traveled far and wide, making sure that the truth was known.

The Apostle who was a missionary, spreading the gospel.

A man who seemed so much like Wood himself.

getty images

Once he was done with the club, Wood admired it in all its beauty. A light, sandy color with a green fiber inserted in it, as a tribute to Langer’s victory at Augusta. The club took him more than a year to construct, and by the time Wood was finished, Langer had already switched to metal woods for the 1994 season. Wood knew the end was coming. He packaged up the work of art, put it in a neat white Wood Brothers box with the black and red lettering, and sent it to Langer’s home. He never knew if it would reach its destination.

Never knew if the man who it was intended as a tribute for would even see it.

It would be the last persimmon driver Wood ever made.

“It’s a beautiful piece of art,” an excited Langer recalled recently. “It truly means a lot to me.”

Not until a few years ago did Wood even know that Langer had it in his possession. He didn’t find out until a friend sent him a video tour Langer did of his home during which he pulled it out and showed it to the camera crew. Almost immediately the thoughts of the lunch with Jackie Burke and Jimmy Demaret came flooding back to Wood; the early days in the shop curing the persimmon heads in the broiling Texas heat; the first success on the PGA Tour; Bob Tway and Jeff Sluman both winning PGA Championships with a Wood Brothers driver; the camaraderie among the shop stalwarts; the highs, the lows.

The clubs.

At the end of it though, it was always about the clubs.

Down to the very last one.

“I didn’t know that was going to be my last golf club I built a driver from scratch,” Wood said. “It was all very poetic when you think about it. That club was my — our — Last Supper.”

Brendan Prunty is a New Jersey-based freelance writer. A former nationally recognized sportswriter for the Newark Star-Ledger, his work has appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated. He may be reached at brendan.prunty@gmail.com.