How do you build a golf ball? It starts with the core.

“It’s really an inside-out process,” Norm Smith says as we hit the factory floor. He’s Callaway’s VP of manufacturing, engineering and quality, and we’re touring the company’s ball plant in Chicopee, Mass., a small city 85 miles west of Brookline, the site of this year’s U.S. Open. Smith’s tan betrays the fact that he’s based out of the Carlsbad, Calif., company headquarters. But his grin suggests that he delights in this New England manufacturing town and is at home amid its whir of production.

“We don’t want to be within a certain tolerance,” Smith says, showing off an X-ray machine that measures construction and core centricity in every ball that leaves the place. “We want to be on target.”

Chicopee is called the “Crossroads of New England” because four interstate highways crisscross its borders and can get you to Boston; Providence, R.I.; New Haven, Conn.; or Albany, N.Y., in under 90 minutes. Manufacturing is in Chicopee’s DNA, dating back to a sawmill built by English settlers in the 1670s. Textile mills followed — cotton and wool mills too. Other industries sprung up, including the production, at the Ames Manufacturing Company, of swords and cannons used by the North in the Civil War. By the late 1800s, Spalding came to town and contributed to a boom in bicycle manufacturing. Spalding made other sporting equipment, too, and soon their offerings included golf balls.

From the outside, the ball plant is wholly unassuming. A small “Callaway” sign — the only hint of the activity going on inside — greets you out front. Interstate 391 runs just east of the property, so the hum of commuter traffic is a constant. The vast Connecticut River, key to the region’s industrial core, is a few par 5s to the west. Dotting the neighborhood are greasy spoons and local sports bars, including the Dugout Café, where you can do a burger and beer for $8.95, and where Tedy Bruschi’s Pats jersey and Manny Ramirez’s 24 hang side by side on a wall. This is a manufacturing town, but it’s a sports town too.

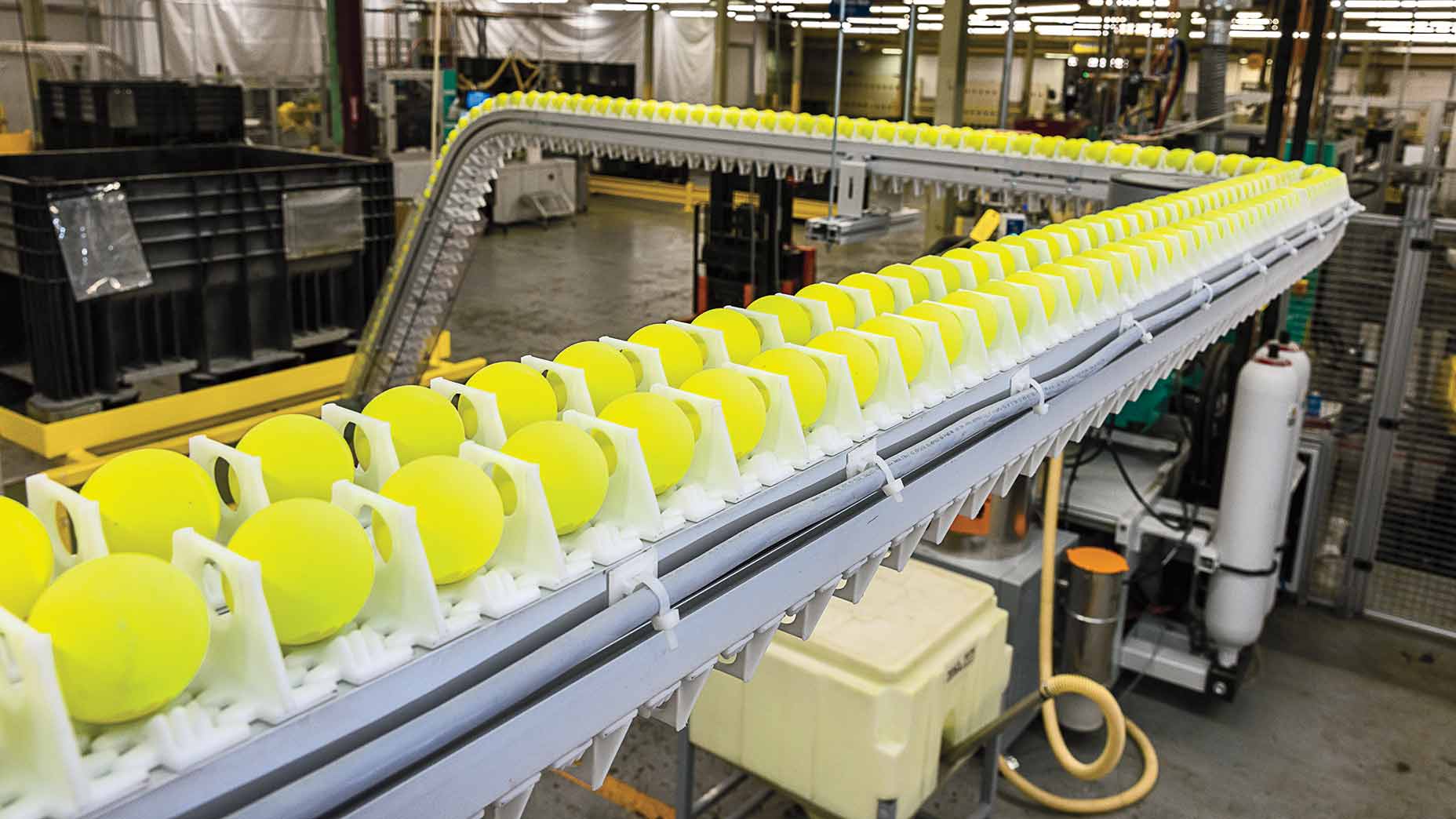

Callaway’s worn brick exterior makes plenty of sense in these surroundings. The shock comes when you get a glimpse of its interior: a labyrinthine sprawl of cutting-edge technology. Employees monitor massive machinery, load conveyor belts, program robots, check computers. Sheets of cotton-candy-colored “rubber blend” careen from one station to the next. Think Willy Wonka meets the Industrial Revolution — but add bots. Cruising the factory is all sensory overload. Can I look in there? Can I touch that? Can I bounce this? Can I take a pic? There’s unfathomable R&D behind every step of the process. And some questions they won’t answer. There’s over a century of institutional knowledge in these walls. There’s a lot that goes into the core of this place.

When Ed Santos was three years old, his family left Portugal for the United States. They settled in Chicopee, where his father got an entry-level job in the factory at 425 Meadow Street assembling golf clubs for Spalding. He stayed for the rest of his career.

“He made a life,” Santos says with passion. “He put us through school. He did everything through this place.”

“Rubber guy” Thomas Cloarec and R&D whiz Dave Melanson, two of Callaway’s finest assets.

Michael LeBrecht

The 1980s were a boom time at the plant, which kept upping its ball-production capacity to meet skyrocketing demand. But when Santos, following in his father’s footsteps, started working on the factory floor in 1993, he was entering a decade of upheaval.

In 1996, Spalding was sold to investment firm KKR for an estimated $1 billion. But a series of missteps and miscalculations left the company in a bad spot, and debt piled up. In 2003, KKR sold off its Spalding brand and “team sports” operation to Russell Athletic. The remaining golf assets were packaged under the old Top-Flite label and undone by bankruptcy shortly thereafter. The plant was suddenly up for auction.

Across the country, California-based Callaway had been trying to enter the golf ball market but was struggling with high production costs and thorny copyright issues. Titleist, Bridgestone and Spalding owned most of the patents — and suddenly, for a price, Spalding’s were available, along with tremendous production capacity in Chicopee. Callaway bought in for $175 million and immediately became a player in the ball space.

But progress wasn’t linear. The economic downturn in 2009 dealt a devastating blow to the golf industry. Layoffs hit. And when Chip Brewer took over as CEO of Callaway in 2012, there was a question as to whether ball operations would be outsourced to a country where costs would be lower. The Chicopee plant’s future was suddenly in question.

New England manufacturing towns know well how this story usually ends. But this one went differently. Executive VP of Global Operations Mark Leposky worked to reengineer the supply chain and update outmoded machinery. Brewer got on board. Forget closing — Callaway doubled down and committed $30 million to the plant instead. That was soon bumped to $50 million. They’ve blown past both numbers since.

A robot moves steel molds in and out of molding presses, where a ball’s core is created.

Michael LeBrecht

Ed Santos can’t believe how things have changed. He survived layoffs that, a decade ago, had cut the workforce to just about 100 employees. Now they number nearly 500. He has ascended to senior production supervisor on the operations team, which means he oversees core molding and core finish. He marvels at the parts of the process once done by hand but now executed more efficiently and effectively by robots. He appreciates how things have changed, and he enjoys seeing the fruits of his labor roll along closely mown greens on the world’s greatest golf courses.

“There’s a lot of pride when you see Jon Rahm out there using a golf ball that’s the same type we make here,” he says. “To see that ball spinning, slow-motion, and to see that [Callaway] chevron [logo] going into the hole — it’s like, Man.”

Santos has two young kids. Sometimes they’ll watch golf on TV together.

“I’ll say, ‘Hey, Daddy made that ball. Somebody on my team made that ball.’”

There are plenty of fresh faces on the floor now. Many come from the Chicopee community, introduced to the opportunity via the plant’s partnerships with local technical colleges. Others with specialized backgrounds come from across the globe.

Thomas Cloarec is one such hire. The 31-year-old hails from France, has a master’s degree in material science and worked at Goodyear before Callaway. He’s a senior process engineer. More simply put, “I’m a rubber guy,” he says. “That’s what I do. I mix rubber.”

Cloarec tries to dumb it all down for me. Like loads of avid golfers, I’m clueless when it comes to the processes of ball manufacturing.

“The first step is like baking a cake,” he says. The raw ingredients are combined, mixed and blended through a complex thermodynamic process. That makes the cake batter. Then comes core molding. “That’s your oven,” Cloarec says.

Cores are covered with color-coded mantles and shuttled, via a feed hopper, to an injection mold machine, where they receive their shiny, polyurethane covers.

Michael LeBrecht

Throughout my hours on the floor, the same phrases crop up: precision technology. Tight tolerances. Process parameters. Measure better, measure more. The goal is straightforward, Norm Smith says: Make the perfect golf ball. The pursuit of that ideal is through obsessive production and quality control. That’s why they collect millions of data points every day, testing for temperature, size, offset, composition, coefficient of restitution, dimple spacing. They process so much data the IT guys bug them about filling up servers.

Dave Melanson is the plant’s director of product engineering. He grew up in Connecticut, just across the Massachusetts border, and has worked at the plant for 24 years. These are his people.

“They’re dedicated, blue collar, salt of the earth,” he says. “As long as I’ve been here I’ve been amazed at who you meet.” Melanson seems like the kind of guy who can give a great pep talk.

“At the end of the day,” he says, “your machines are machines, right? Push a button and it’ll start making stuff. But it’s people who run those machines, who do the setup and pay attention to the quality. Ya know, success is really the little decisions the workforce makes every day because machines will just blindly spit out parts.”

Advanced vision systems inspect every golf ball for abnormalities prior to the finishing operations.

Michael LeBrecht

Melanson takes pride in every step of the process. He likes seeing Xander Schauffele using a Callaway on Tour. He likes seeing employees invested in the work and the results. He likes seeing jobs come to western Massachusetts.

“Job offerings in manufacturing aren’t what they once were,” he says. “And golf balls are an appealing product to make.”

How do you build a golf ball? You need materials and machines and people. You mix the rubber. You mold the core, grinding it down to make sure it’s a perfect sphere. Around that you add a mantle, maybe two. You add the cover. You paint the ball and decorate it and put it in a sleeve alongside two others just like it. Gather four of those sleeves and you’ve packaged a dozen balls. Now do it again, tens of millions of times. The unassuming plant on Meadow Street is supplying golf balls to the world. Unlike the building they’re made in, the balls are shiny on the outside.

“There’s that juxtaposition of new equipment and investment,” Melanson says of his place of work. “You know, the shell is a little bit old, but what’s happening inside is absolutely state of the art.”

None of this means you won’t lose your own Callaway Chrome Soft in the woods or the weeds or the water. But when you do? You’ll know where that next one comes from.