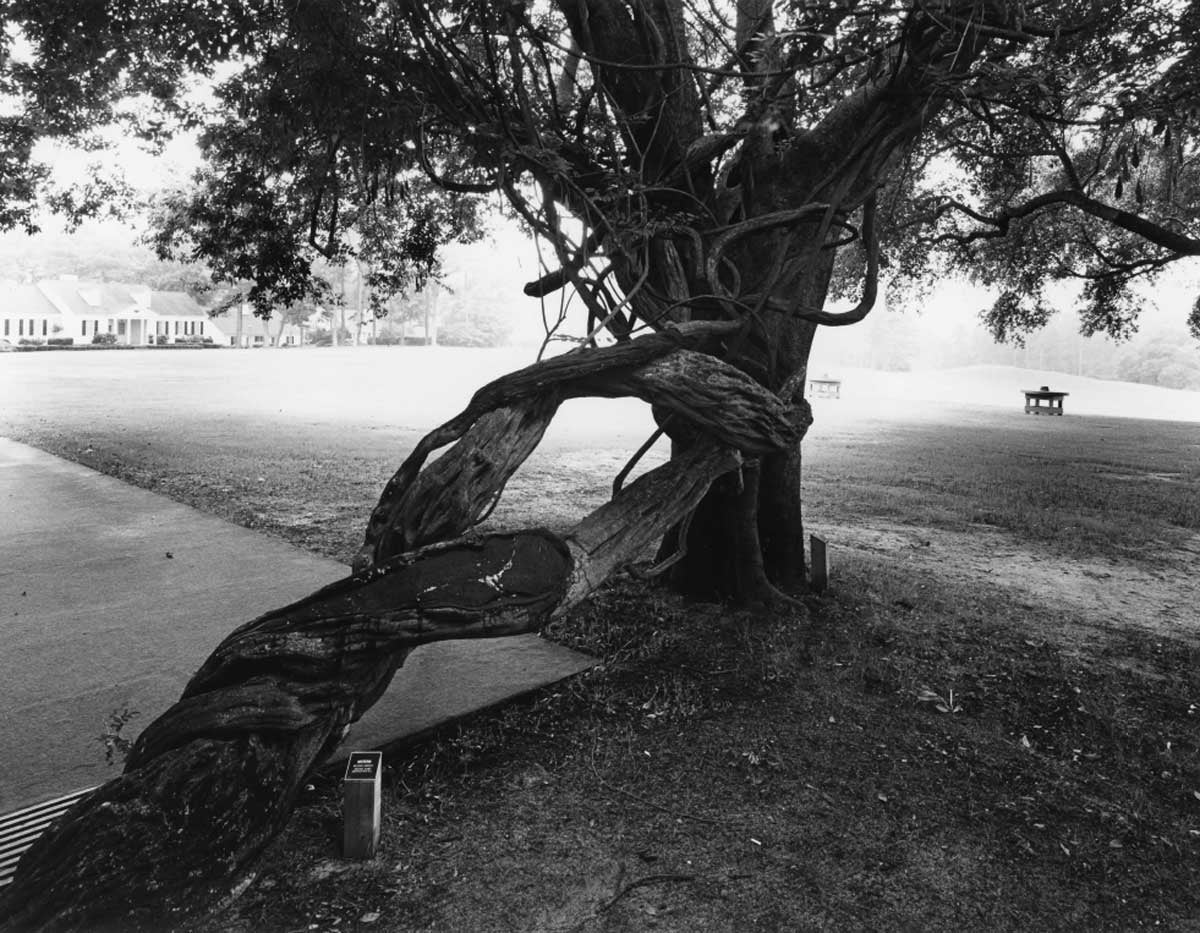

The first tee and clubhouse in July 1978.

James R. Lockhart

Despite the long-used adage that goes, “Visiting Augusta National is like going back in time,” rest assured, it changes.

Less than 20 hours after Hideki Matsuyama won the Masters last spring, a tree removal crew had already uprooted an aging pine behind the 14th green. Will anyone notice that this week, when patrons are allowed back on the grounds? Nope. Because every alteration is done so meticulously, and often under veiled circumstances, how the property looks today seems to align exactly with how we remember it 10, 20 or 30 years ago.

To get a view of how Augusta National looked 40-plus years ago, we can lean on the United States government and its National Register of Historic Places. In the late 70s, Augusta National’s property — once one of the most significant plant nurseries in the country — was nominated to join, but there was nothing easy about the process. In order to be accepted, the notoriously private club had to open its doors to surveyors, historians and staffers from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to assess its value and significance.

The process took years.

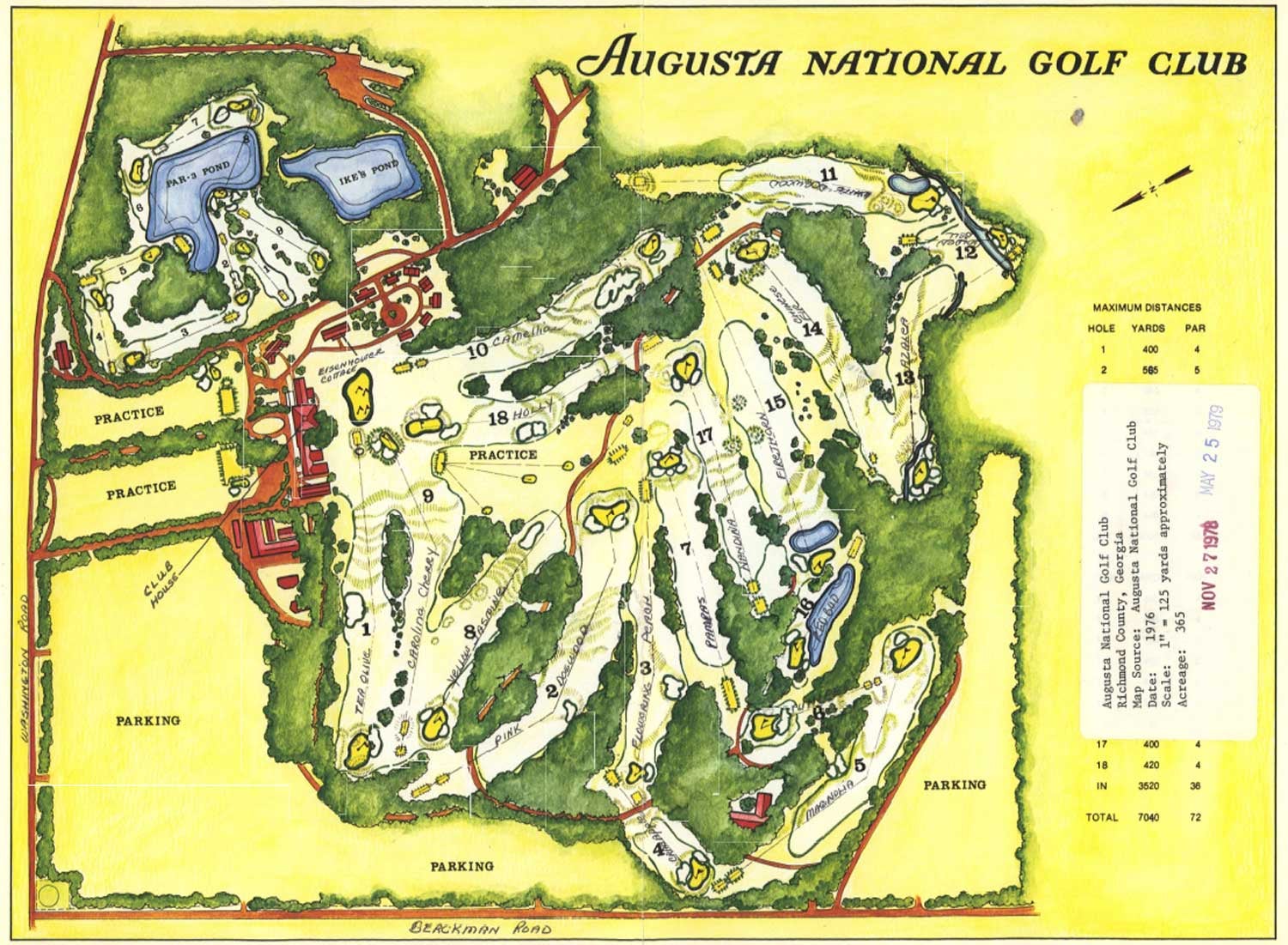

While the nomination was eventually approved, it was not until after careful consideration of the grounds, its buildings, its history and its relevance to the game of golf. As a result of such a thorough appraisal, we are treated to many photos of the club from that moment in time, nearly 45 years go, which you can see below. We’ll start with a map of the property included in the report prepared by staffers of the Georgia Historic Preservation Division.

A map of the grounds of Augusta National from 1976.

Courtesy Georgia State Historical Division

Perhaps the best living relic of Augusta National’s history is the wisteria vine that clings to the clubhouse. Wisteria was one of the many plants that flourished at the Fruitlands nursery in the late 1800s and early 1900s, before Bobby Jones even showed interested in the property. In particular, the Wisteria vine that has long gripped on to the clubhouse was special — it was the first Wisteria to exist in the United States. As you can see in the photo below, there’s a commemorative block of wood clarifying its significance. Taken in July 1978, the photo clearly shows benches in the background likely marking the 1st tee box.

James R. Lockhart

Once the entrance to the nursery, Magnolia Lane was described in the Historic Places report as “Avenue of the Magnolias,” which might be my preferred name, to be frank. This view is from what is now called Founder’s Circle, looking back at Washington Road. And the second photo would be 180 degrees in the opposite direction, straight at the clubhouse.

James R. Lockhart

David J. Kaminsky

The clubhouse was the initial focal point for nomination into the Register of Historic Places. Was this property significant because of this house? Or for something else? That was the question on the mind of Carol Dubie, a spokeswoman for the register. And she wasn’t alone in that thinking. The clubhouse used to be a home for the Berkmans family, looking out over their sprawling nursery. It was built in 1854 by the original owner of the property, Dennis Redmond, and make from concrete. According to the records, it was the “first such house in the South.” Redmond reasoned that concrete was better than brick at insulation, pest control, and would be overall much more efficient. (Imagine Augusta National with a brick clubhouse! It changes the vibe, for sure.)

When being considered for the Register of Historic Places, the report makes clear that Fruitlands and the clubhouse buildings, on their own, were not enough. Multiple reporting chiefs noted that the “significance of the golf course needs to be addressed” in order to fully understand the property as an historic place. At the time of that consideration (January 1979), the Masters had not yet been held for 50 years.

James R. Lockhart

Surely no one at the club was worried about its significance in the world of golf, but Georgia Department of Natural Resources employees were not about to approve this without taking a much closer look. Kenneth Thomas prepared the report on the golfing significance of the club, citing this line from world-famous golf architect, Robert Trent Jones:

“The Augusta National is the epitome of the type of course which appeals most keenly to the American tastes, the meadowland course …The (Bobby) Jones conception, incarnate in Augusta, was that the course should be a true test of championship golf, but, more than that, that it should be a pleasure for all classes of golfers to play … the course is unmatched in the physical facilities it affords for watching a major tournament.”

Little more needed to be said. Thomas submitted his report on April 12, 1979, the first day of that year’s Masters, which was won by Fuzzy Zoeller. Forty-three days later, Augusta National was officially listed in the Register of Historic Places.

David J. Kaminsky

If Augusta National specializes in anything, it’s simple elegance, which you can see both above and below. Above is Ike’s Cabin, named for former president Dwight D. Eisenhower, who loved Augusta National so much he routinely vacationed there during his time in and out of office. He made a habit, through a strong relationship with former Augusta National Chairman Cliff Roberts, that Eisenhower would spend time at Augusta National immediately after his elections, win or lose. Like many buildings on property, the facade of the Eisenhower Cabin has changed very little over the years. Below and left, you can see what the inside looked like in July 1978. Farther down you’ll find some simple, quaint fireplaces and the main stairwell in the center of the clubhouse, from which many VIPs will access the veranda for lunch on the balcony during Masters week.

James R. Lockhart

David J. Kaminsky

David J. Kaminsky

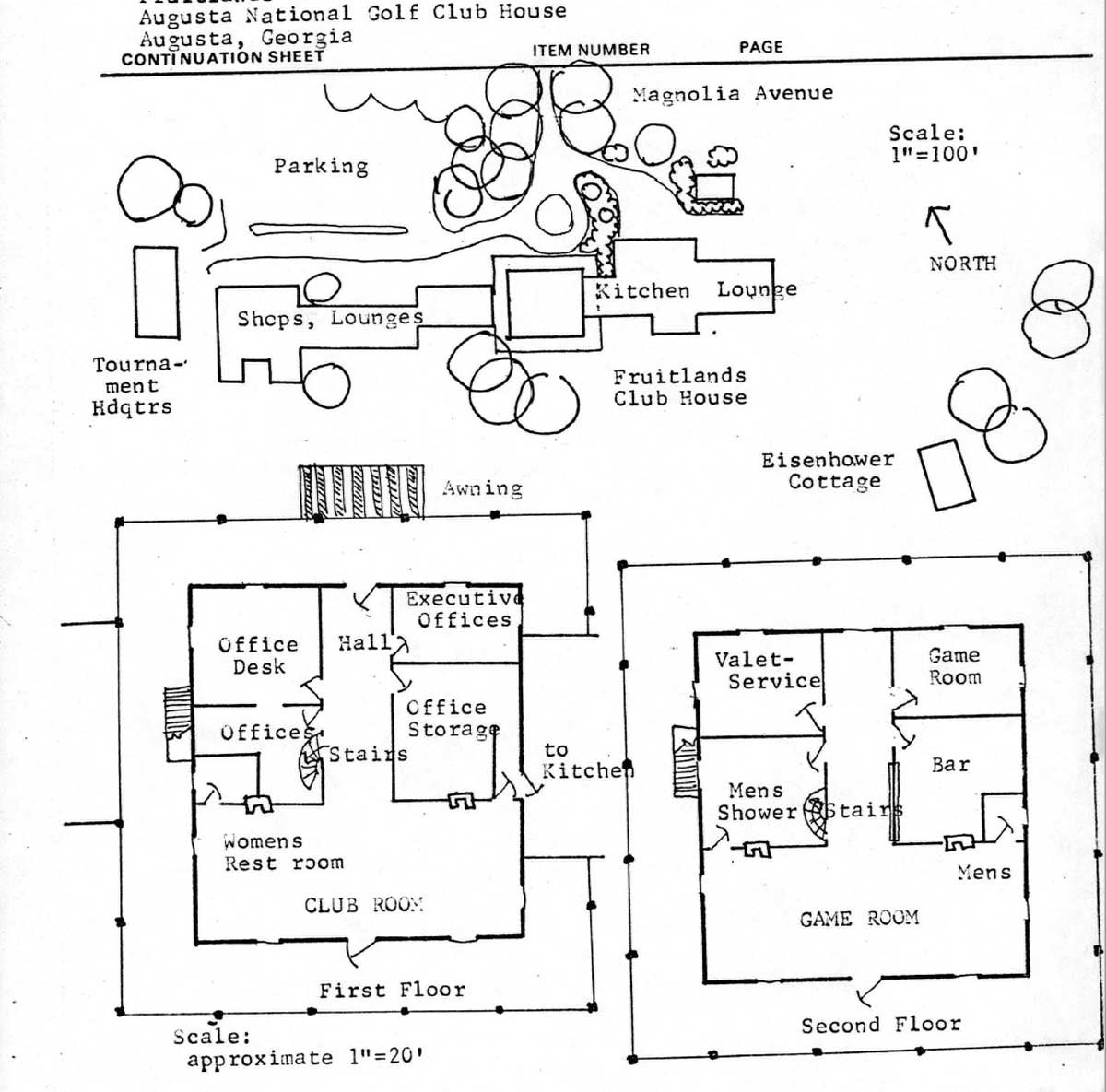

A rough floorplan of Augusta National’s clubhouse, circa 1978.

Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Only at Augusta National do things always seem the same. But that’s never really the case, here or anywhere, is it?