Last September, at age 59 and in his 36th USGA event, Gene Elliott was finally able to call himself a USGA champion.

USGA Museum

At the final of the 2021 U.S. Senior Amateur, Gene Elliott, then the second-best senior amateur in the world, faced off against Jerry Gunthrope, a construction services professional who, as an amateur golfer, had been competing at the national level for only two years. As Bill Murray might say, it had the makings of a Cinderella story.

In the end, it wasn’t to be. Elliott took the title with a 1-up win over Gunthrope, but that took nothing away from Gunthrope’s accomplishment. At age 57, and little known on the elite mid-amateur circuit, he’d blown through the field at the Country Club of Detroit, which was stocked with hardcore amateur players, to make it to that last match.

“I looked at Gene in the finals and asked him how many USGA championships he’d played in,” Gunthrope recalls. “It was my second. It was his 36th. People said to me, ‘Where in the world did [you] come from and why [are you] here?’ I did it differently.”

Balancing family commitments is as much of a challenge as the game and the finances.

Amateur golf doesn’t get the headlines it once did — when, for example, Bobby Jones, at age 28, won the Grand Slam in 1930, collecting the U.S. and British Opens and the U.S. and British Amateurs in the same year. But non-collegiate amateur golf still occasionally has its moments. Jay Sigel, a former insurance man, and Stewart Hagestad, who once worked in real estate, are now golf-world names of note, as are Carol Semple Thompson, dominant for 30 years starting in the 1970s, and current senior-am dynamo Ellen Port, a retired coach and educator. Both women have won seven USGA titles — Jack has eight, Tiger nine.

What’s little talked about is just how much money it costs these amateurs to compete at the highest level. It’s not the world of country club member-guest tournaments, which can still cost more than $1,000 for a three-day event. It’s the lure of getting an invite to play in storied mid-ams like “the Coleman” at Seminole, “the Crump” at Pine Valley or “the Thomas” at Los Angeles Country Club. How men and women — with jobs, spouses, kids and many other obligations that kill practice time — manage to compete at this level is not easy or cheap. When it works, it’s a fine balance; when it doesn’t, it’s costly in all sorts of ways.

The money spent on a typical four-day event, with practice and competition rounds, averages about $3,000, which includes entry fee, caddies, airfare, hotel, food and drink. It’s not uncommon for an elite amateur to play 15 events a year — to the tune of $45,000. Top seniors, freed from work and kids, might play 35 events a season in an effort to earn enough points in the World Amateur Golf Rankings to automatically qualify for events like the U.S. Senior Amateur. That campaign can cost them more than $100,000.

“It’s not much cheaper than playing the PGA Tour, but you’re not playing for money; you’re playing for gift certificates,” says Billy Mitchell, 57, a personal trainer in Buckhead, Ga., who briefly played professionally in his mid-20s. “It’s an expensive habit.” But one that Mitchell, who won low amateur honors at the 2021 U.S. Senior Open and made it to the quarterfinals of the 2019 U.S. Senior Amateur, is certain helps his business.

“Once you get a taste of it, it’s really hard not to do it,” he says. “I don’t play golf much for fun because I would just rather compete. What’s the return on investment on this? You don’t calculate that. But I can tell you this: If I don’t play at the level I do, then I don’t train the Tour players, and they bring the club players [and their business to me].”

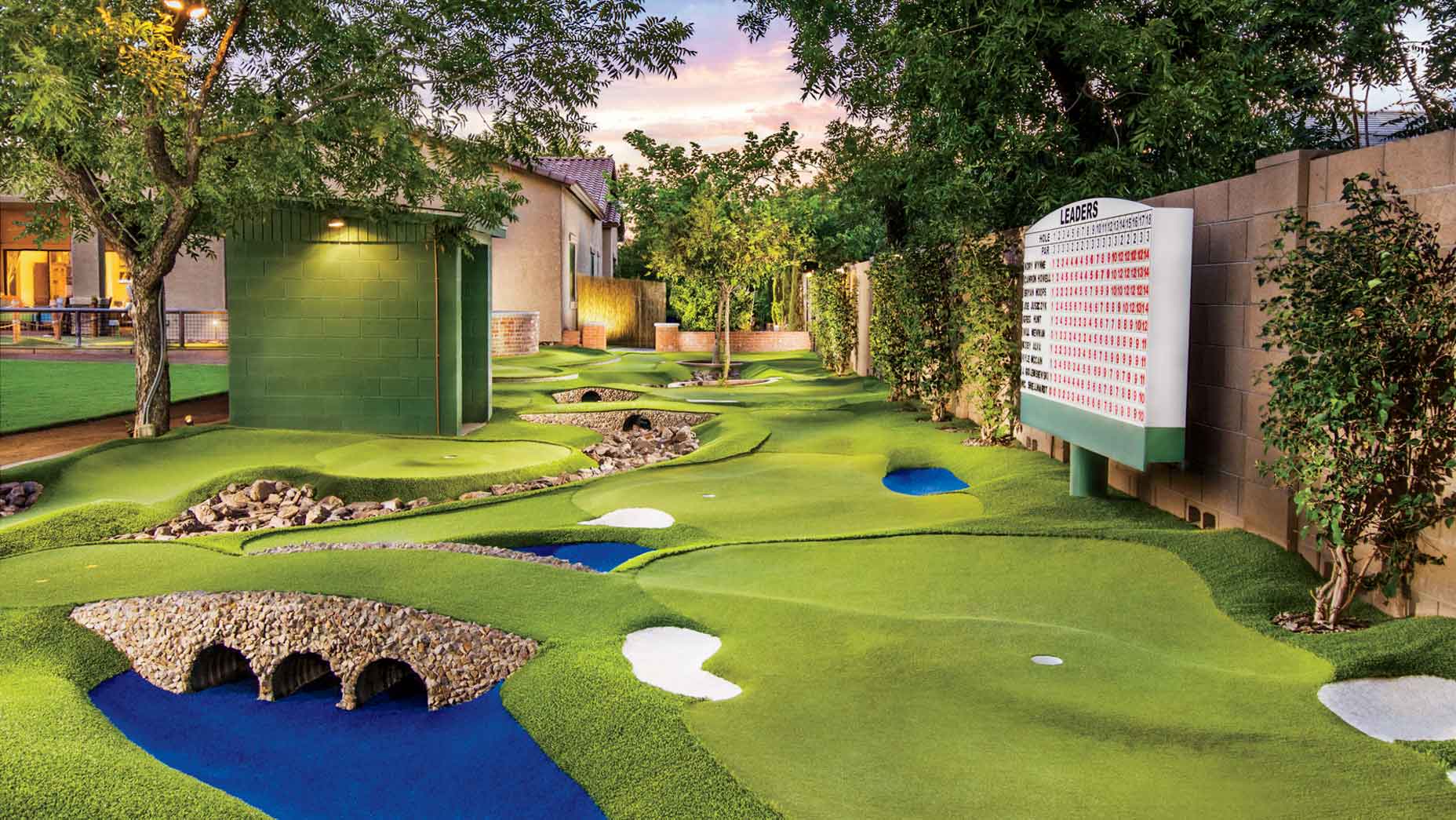

For some elite amateurs, there are financial costs beyond those of tournament week — like the price of staying sharp if you live somewhere with four seasons.

“It’s hard to come from Vermont and play at Seminole in April,” says Eoghan O’Connell, a member of the winning Walker Cup team in 1989 and a two-time winner of the Coleman.

For others, that off-season gives them the energy to get ready for the next year — and to save some cash.

“It keeps that fire going in me, and it helps with the balance of things,” says 34-year-old Julia Potter-Bobb, who has won the U.S. Women’s Mid-Amateur twice while based in Indianapolis. “I’m not sitting here in a bad financial situation, but you still have to make sure you know where your money goes.”

Gunthrope made the decision to limit his travel, and thus his costs, when the last of his kids was born.

“My wife was pregnant with our third child, and I was playing in the Michigan Amateur,” he remembers. “I got a talking-to about how tough it was to have two kids and be pregnant with a third. That put the end to me being away.”

Balancing family commitments is as much of a challenge as the game and the finances.

“People playing in mid-am events are usually younger and don’t have kids,” says O’Connell, who is married with five children. “Once you have kids, you don’t want to do it as much. The weird thing for me is my golf began to deteriorate as I had kids!”

Port, the decorated women’s amateur, says her husband, Andy, was always supportive, creating a team atmosphere to bring their kids on board. She also worked as a teacher for three decades, which gave her summers off to practice and compete.

“I learned how to kick it into gear at the right time,” she says. “It made me that much more hungry and fresh. I knew I had only a few opportunities each summer.”

Hagestad, who at 30 just won his second U.S. Mid-Amateur Championship after playing on his third Walker Cup team, says he’s begun to pare down his schedule to just the top events. He’s in his last year of business school and focused on what comes next.

“I’ve been lucky to do some special things in golf and meet amazing people, who have become friends,” he says. “I love competitive golf for sure. But I didn’t turn pro for a reason. It’s the balancing act I’m most proud of.”

Want Paul Sullivan’s advice on all things golf-related in personal finance? Send your questions to moneymailbag@golf.com.