The internet is a wealth of information, but it can’t answer the questions that really matter.

Is there a God?

What’s the meaning of life?

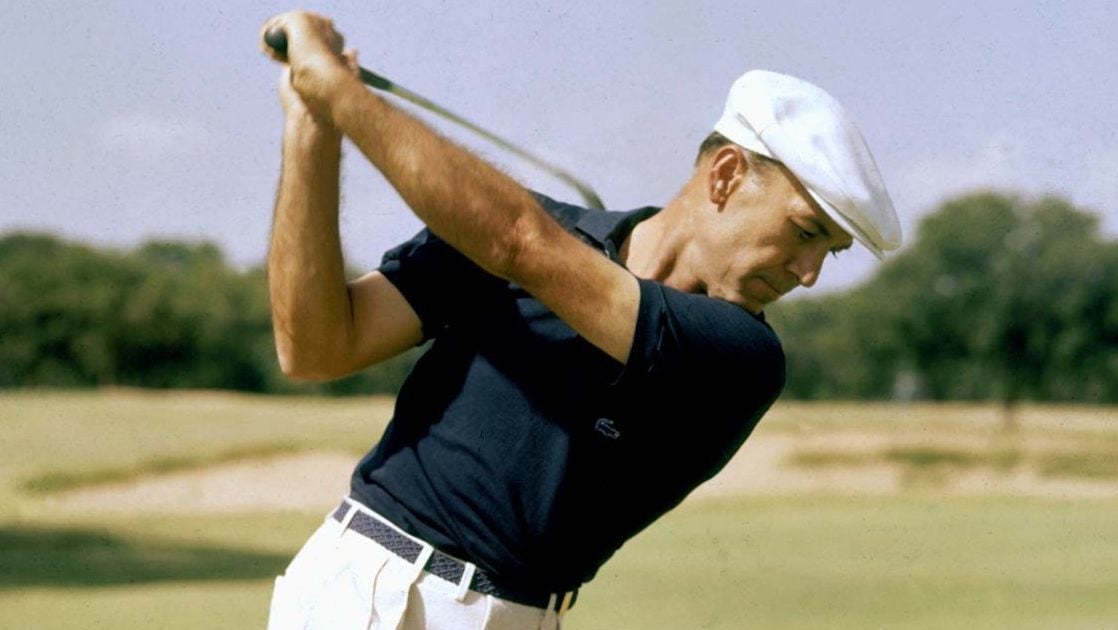

How good would Ben Hogan be today?

That last one is a topic my friend, Hayes, and I have debated off and on for decades.

Hayes is a member of the Church of Hogan, a true believer, convinced that the man walked on water hazards, never missed a green in regulation and would dominate the modern game.

I am a Hogan skeptic. Though I’m sure that he’d have a fine career today, I don’t buy the notion that he’d reign supreme. A top 20 guy is how I see him, with a handful of wins and probably a major — something of a sepia-toned Corey Pavin.

That our argument is unresolvable is what makes it entertaining.

Hayes trots out his ”evidence,” while branding me as a benighted upstart. And I fire back with mine, while casting him as a blue-blazered Archie Bunker, a tweedy dinosaur, romanticizing the past.

It has dragged on in this way for roughly three decades, each of us biased, neither budging. Like a pair of academics in a heated dispute, we care so much because the stakes are so small.

But at least we laugh about it, which is more than I can say about some partisans in this unwinnable fight.

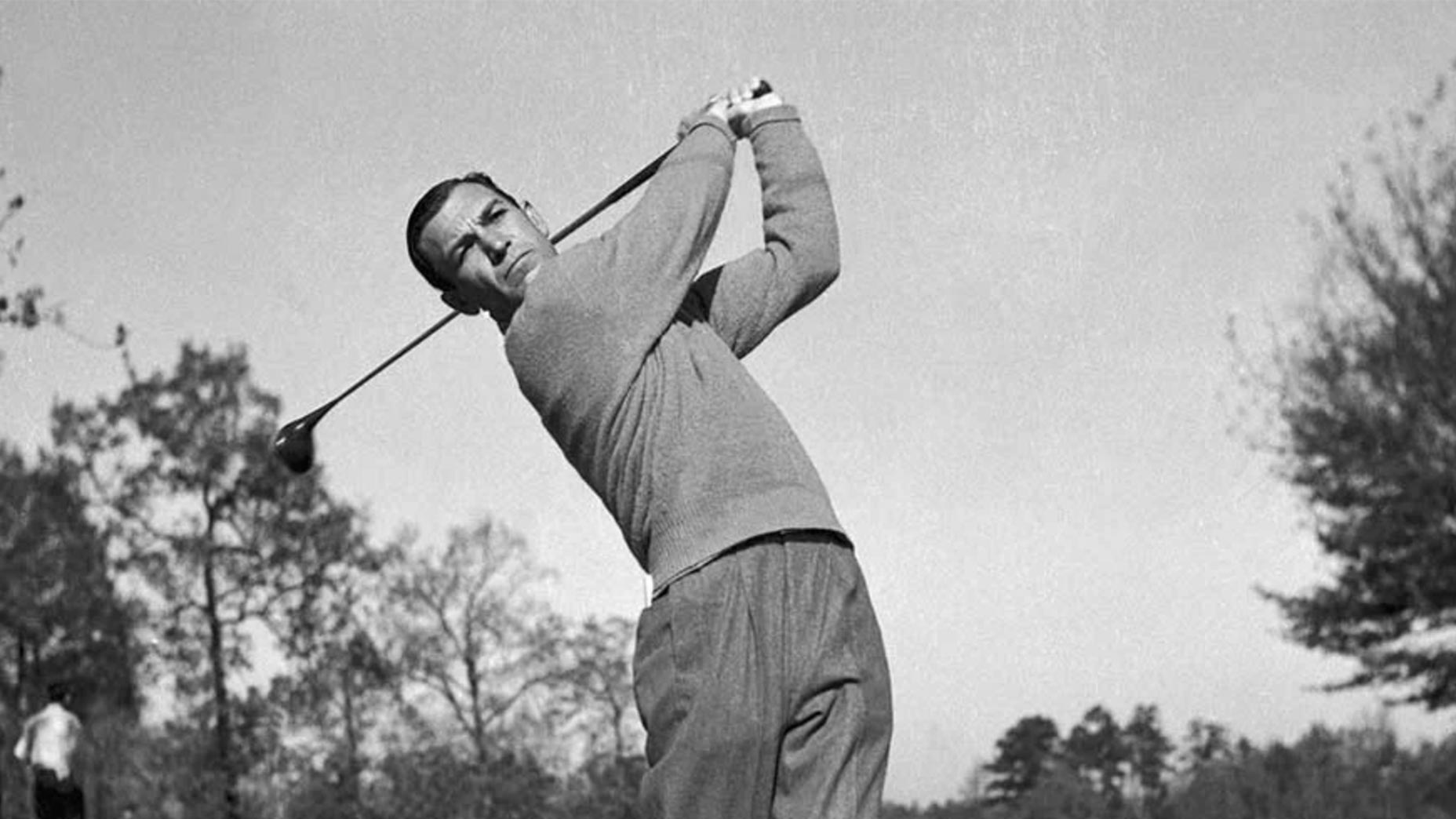

The mystique of Hogan, pictured in 1941, endures to this day.

getty images

I had my first encounter with one of their kind at a backyard cookout in the summer of 2000. Only weeks before, Tiger Woods had made a blood bath out Pebble Beach, bludgeoning the field in the U.S. Open for a record-smashing 15-shot win. Around the grill that afternoon, a bunch of us got talking golf and Tiger, everyone gushing in agreement that the game had never seen his likes before and probably never would again. Everyone, that is, but a graybeard in the group. He looked in his early 70s, and he stood at the outskirts of our circle, saying nothing but shaking his head as we spilled superlatives over Woods.

Finally, he spoke.

No disrespect to Tiger, he said, but he’d been watching golf since the Howdy Doody era. Allow him to serve up some perspective.

There was a hint of condescension in his voice, and a tinge of pity on his face, the patronizing look that older people often wear when informing younger people of the many wondrous things they missed.

Woods was great no doubt, Ol’ Hickory Sticks went on. But stop kidding yourself, kids. Ben Hogan would have wiped the floor with him.

I can’t remember if I chuckled, but I might as well have.

What I said was something in this spirit: “Hogan? Shrimpy fella with the putting problems who played in an era when four guys had a chance of winning? Yeah, right.”

Harmless cheekiness, I figured. Standard sports-fan swordplay. I figured wrong. Hickory Sticks grew visibly upset, face reddening, eyes widening. He took a half-step toward me. How dare you, he huffed. It wasn’t a question.

The depth of his umbrage was unsettling. I worried for a moment that we were on the brink of a Bob Barker vs. Happy Gilmore brawl.

An extreme example? Sure. And yet instructive. Touchy subject, Hogan. Little had I realized that Hayes and I were treading on such fraught terrain.

Generational debates about athletic greatness are as old as the ancients. The Iliad is peppered with comparisons of warriors past and present, and you can bet that when Homer sang of “swift-footed” Achilles, he heard it from the pro-Hercules crowd.

People get worked up over their heroes. That has always been the case. But I maintain that no band of sports-world loyalists has ever been more rabid — or defensive or prone to exaggeration — than the hardest of hardcore Hogan devotees.

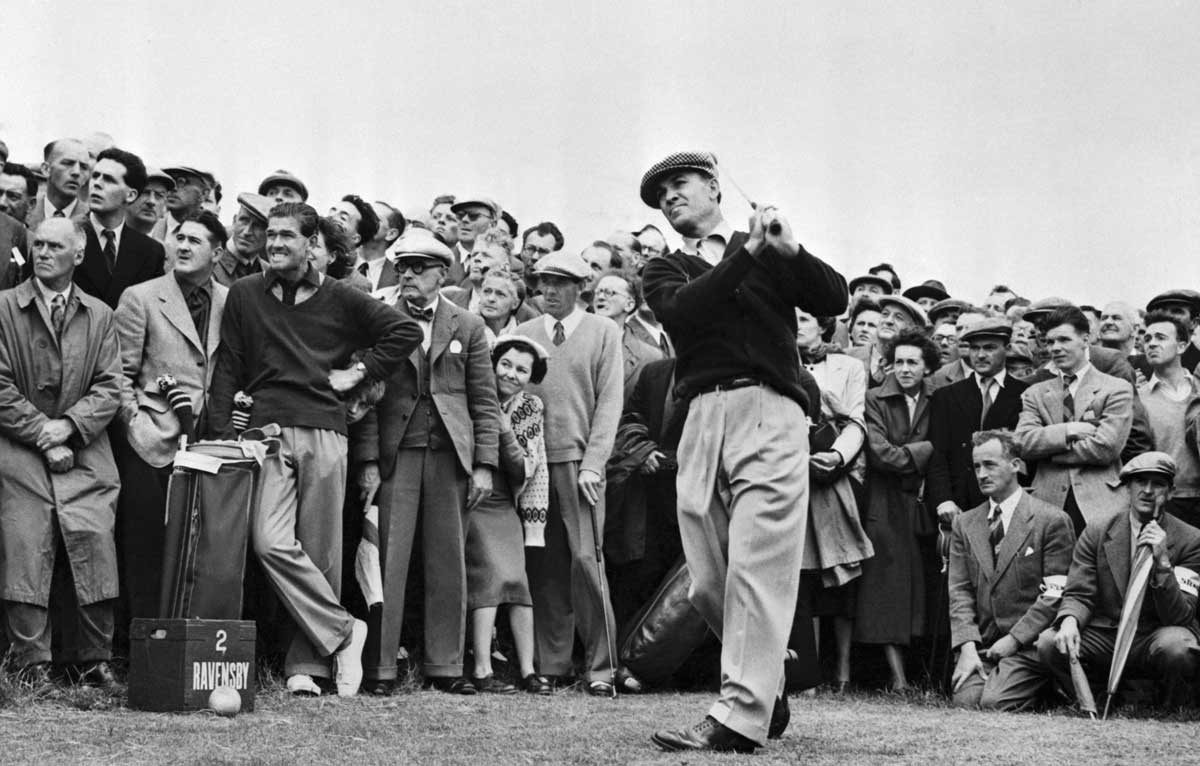

Just more than a half-century has passed since their idol played in his last professional event, limping off the course at a tournament now known as the Houston Open, legs aching, short game shot. His most notable achievements are beyond dispute: the up-from-nothing rise; the nine major titles and 64 Tour wins in a career interrupted by a world war and a car wreck; the magical 1953 season, when he claimed three quarters of the modern Grand Slam.

Any Hoganist can regale you with those facts. Some go farther, though, bubbling forth with tales of exploits that verge on folklore. These people don’t do banter. They brook no disagreement. They are easy — and tempting — to provoke.

A reminder of this came a few weeks back, when I asked Google for its thoughts about Hogan’s contemporary prospects, a search that led me through a labyrinth of golf-related chat rooms.

“Who else agrees with me that Ben Hogan would be irrelevant on today’s PGA Tour?” a commenter posting as Vijay4Life had written.

The Hogan faithful were there to take the bait.

“Irrelevant? C’mon man, you cannot be serious with that drivel.”

“It wasn’t uncommon for Hogan to hit 18/18 GIR, the guy was that good.”

“If he had today’s technology, he wouldn’t miss a green in regulation for like 6 months.”

“Dude, why all the Hogan hate?”

Vijay4Life seemed gleeful at the outrage.

“If you want to believe in fairy tales about golfers of olden times, go right ahead. You’re welcome to believe in things like God, tooth fairies, and that Ben Hogan could knock it stiff from 175 every time.”

“He just wants to incite,” a Hoganist warned.

Someone else posted a “butt hurt” meme.

Probably my buddy, Hayes.

Anyway, you get the gist.

If Hogan had today’s technology, he wouldn’t miss a green in regulation for like 6 months.

It was a juvenile thread that I also found depressingly familiar. Clicking through it, I heard echoes of my own adolescent sniping over Hogan, and I recognized my kinship to an internet troll, spouting loosely formed opinions but mostly just trying get a rise.

Never mind that certain Hoganists were borderline deluded. Who was I to mock them? I was no better. It was time for me grow up and ditch the wisecracks, or at least make a stab at more substantive remarks. I was long past due to take up the discussion with mature and measured sources, established voices who, unlike me and Hayes and Vijay4Life, weren’t speaking sideways out of their hurt butts.

“He’d be just as good or better today than he was back then, and just as Tiger made his peers look like also-rans in his prime, he’d make Justin Thomas and Dustin Johnson etc look inept.”

That was the reply I received from NBC/Golf Channel analyst Brandel Chamblee when I first put the question to him over text.

Chamblee, a native Texan, is a Hoganist of the highest order, but he’s too clear-eyed to be lumped in with the cultists. True to reputation, he’d assembled a scaffolding of yellow notepads to support his claims.

Hogan would make them look . . . inept? I asked, in a follow-up Zoom call.

Now, now, Chamblee explained. He wasn’t trying to denigrate today’s Tour stars. He was simply out to underscore the rarity of Hogan’s gifts, a marriage of intellect, intensity, and athleticism whose only modern analog he saw in Tiger Woods.

Where I’d always pictured Hogan as a pipsqueak who’d be physically outmatched in the modern era, Chamblee presented a different image. He likened Hogan’s build to Rory McIlroy’s, and cited estimates suggesting that his clubhead speed today would be right there with McIlroy’s as well, upward of 122 miles per hour.

Distance would not be a deterrent for him.

In fact, Chamblee said, because Hogan swung without resisting — no hanging on, no holding off — he would likely blast it farther than a guy like DJ.

In Chamblee’s view, modern equipment would augment Hogan, further separating him from his competition. So would modern information.

“Guys these days play a round with Bryson and walk down the fairway like they’re talking to Einstein,” he said. “I give credit to Bryson for being curious but. . . “

Hogan was a brainiac of a different order. As backup, Chamblee told the story of the Hogan acolyte, Gardner Dickinson, surreptitiously slipping Hogan IQ questions over the course of many rounds together, yielding a guesstimated score that marked Hogan as a genius. Maybe he really was. Maybe he wasn’t. Either way, the takeaway was this: imagine what a man who found answers in the dirt could do with a Trackman in his hands.

Now, as then, Chamblee said, Hogan’s “feral mind” would make him a pioneering tinkerer and thinker. His smarts would also help him see through the “chicanery” that often masquerades these days as a sound instruction. Unlike Tiger, Chamblee added, Hogan would not have turned his swing over to others. It was not in his makeup to “subjugate his talents to someone else’s ideas.”

Oh, and about that glitchy flatstick: the heebie-jeebies, Chamblee said, only struck Hogan late in his career (some have suggested they were brought on by depth-perception issues caused by the car crash). Before that, he was a boss of the moss, praised by no less than the short-game wizard Bobby Locke as the finest putter in the game.

Hogan would lay waste to fields today.

In conclusion, Chamblee said, “Hogan would lay waste to fields today.”

Got it? Good.

Now, brace for a rebuttal.

Mark Rolfing did a stint on Tour in the early 1970s, shortly after Hogan hung up his spikes, before shifting to a different role inside the ropes. As an on-course reporter and analyst for NBC/Golf Channel for more than three decades, he has had a closer view than most of a game in evolution. The changes have been massive, and several, Rolfing told me, would not favor Hogan. They’d neutralize advantages he once enjoyed.

Take driving accuracy, one of his legendary strengths.

“Its relevance in today’s game is not a major factor,” Rolfing told me. Check out the stats. The most accurate drivers “rarely end at the top of the FedEx Cup rankings.”

Course management, too. Hogan was a master. It matters much less now than it did then.

“Today’s players basically come up with a plan for a round of golf and that’s it,” he said. “Once they get into it, there’s not a lot of variances. They hit it far, find it, and then grab the next club.”

Ball-striking has become “so condensed,” he added, “that hot putting weeks are what win tournaments now.”

Rolfing said he didn’t doubt that Hogan would still be a star today. He just wouldn’t be the alpha. That’s not how it works in the post-Tiger era. The days of solo rule in golf are done. “I don’t think we’ll even have a Big Three again,” Rolfing said.

The talent pool is too deep and level. For proof, look no farther than the betting lines.

Most any week on Tour, you can find a wager that pits the field against the top nine players. The odds are usually close to even. If this were Hogan’s era, that wouldn’t be the case. “You would take the top nine players every time and win,” Rolfing said.

This brings up a point that’s pretty much impossible for Hoganists to counter. In Hogan’s prime, golf was a parochial pursuit compared to the global game it is today. There are many ways to measure this. Here is one. At the 1953 U.S. Open, where he won the last of his major titles, Hogan beat a field composed entirely of players representing the United States. Last year, at Torrey Pines, competitors from 23 different countries came up short against the Spaniard Jon Rahm. As Team USA has learned in basketball, globalization makes winning harder. It swells the population of legitimate contenders. I don’t believe it’s trolling to tell a Hoganist: Your man had it easier that way.

You might even get an interesting response. When I offered this perspective to the World Golf Hall of Famer Lanny Wadkins, a friend and frequent playing partner of Hogan’s, he didn’t just refute it. He turned it on its head.

Tougher nowadays? Wadkins scoffed. The contemporary Tour may have players from all over, but it is also a comparative cakewalk, the purses extravagantly fatter, the equipment comically more forgiving.

“Tell you what, let’s take (today’s pros) back and play with the wooden drivers and spinny balls we used and see how they do,” Wadkins said. “We had to hit all kinds of shots. We played with much more imagination.”

More desperation, too, Wadkins said. Miss the cut, and you might not make the rent. The stingy climate produced a rough-edged breed.

“Guys like me and Hale Irwin and Raymond Floyd, we were mean, we were junkyard dogs,” he said.

Hogan even more so. The Ice Mon moniker was not for nothing. Transported to the present, you would not find him posting selfies or spring-breaking with Jordan Spieth.

Sharp and focused, he would cut through contemporary fields like butter.

“It’s different now,” Wadkins said. “Guys are soft.”

I might have argued, but I was scared that he might throttle me over the phone.

It’s different now. Guys are soft.

There is, of course, no metric for tabulating “softness.” Nor is there enough data of any kind to bring credible closure to the GOAT debate. If he knew of any, the golf-stats guru Mark Broadie would be happy to share.

“Even with something like the 100-meter dash in the Olympics, where you’re competing at the same distance over time, it’s difficult enough to make comparisons,” Broadie said.

Good luck, then, with golf, which brings a universe of variables into play. Different training and equipment. Different courses and conditions. Different levels of competition.

“We just don’t have a way of measuring those things across generations,” Broadie said.

Not that people haven’t tried.

In “The Hole Truth: Determining the Greatest Players in Golf Using Sabermetrics”, the journalist Bill Felber aims to make good on the promise of his book’s subtitle. Central to his calculations is a stat known as a z-score, which measures, in numbers of standard deviations, how a player’s score in an event compares to that of the field average. It is, in essence, a cousin of strokes gained. To arrive at his rankings, Felber tallies z-scores into career totals. Along the way, he tries to minimize margins of error by eliminating outlier scores.

What he doesn’t do is fill a gaping hole in his analysis. At no point does he grapple with the fact that you can’t rank z-scores across generations without also quantifying differences in strength of field from one era to the next. And you can’t quantify those differences in strength of field because, well, you can’t.

You can only make assumptions.

Did Rahm face far stiffer competition at the 2021 U.S. Open than what Hogan faced at the national championship in 1953? I think he did. But I can’t prove it.

Neither could Felber if he wanted to, but he glosses over that.

If you’re an ardent Hoganist, you may be glad to hear of the flaw in Felber’s system since Hogan doesn’t fare so well in Felber’s rankings. He comes in 10th on the all-time career roster, behind Jack Nicklaus, Walter Hagen, Patty Berg, Tiger Woods, Sam Snead, Louise Suggs, Mickey Wright, Annika Sorenstam and Gene Sazaren.

Of course, even if those rankings were airtight, I doubt that they’d do much to sway opinions. In this debate, it’s not the numbers but the narrative that carries weight.

Hogan’s resonates uniquely. Of multiple biographies, my favorite is Jim Dodson’s “Ben Hogan: An American Life.” It was certainly that. The organizing themes of Hogan’s story — the hardscrabble beginnings and unlikely ascent; the resilience, self-reliance and resourcefulness, grinding past calamity to conquest — are the underlying themes of the “American story.” The gritty underdog. The cowboy going it alone. People love that yarn. They’re protective of it. They’ll defend every thread of it, whether fact or fable. Adulation for Hogan the golfer is tied up with worship for Hogan the archetype, and longing for the era that produced him — the good old days when the game required more artistry and players weren’t so soft and needy. It’s an outlook rooted in both truth and fiction. Nostalgia might not be a river in Egypt, but it’s still a form of denial.

Hogan, at Augusta National, won a pair of green jackets.

getty images

The beauty of Dodson’s book is the way it humanizes Hogan, giving him dimension, fleshing him out in all his strengths and flaws. It’s the same portrait the author sketched when I asked him how he thought his subject would stack up today. Dodson said he thought that Hogan would more than hold his own. But, he added, his greatest asset wouldn’t be his driver or his irons. It would be his insecurity. “Nothing motivated him more than his fear of being seen as a loser,” Dodson said.

The man Dodson depicts sounds relatable and likable. It’s fair game to admire him. It’s also fair game to poke holes in the myth.

Over the years, I’ve stopped counting the tales I’ve heard of Hogan on the range, hitting ball after ball, hour after hour, with such precision that his caddie never once had to move more than a half-step to collect them. The laws of physics work heavily against this. Some accounts have even had Hogan one-hopping dozens of consecutive drives into a small basket more than 250 yards away. While I have no doubt his practice sessions were stripe shows, I retain my right to note that these are things that Iron Byron couldn’t do. I feel the same about such stories as I do toward reports of Sasquatch sightings. Incredible! Amazing! Where can I see the footage?

I’m not trying to be flippant, at least not as I was at that cookout years ago when I nearly got a beat-down from a crotchety golf fan twice my age. The Hogan debate is not a hill I’m prepared to die on or even take a punch on. What’s more, I don’t think I have much to add to it. I’ve come to realize that when most of us weigh in on Hogan, we reveal less about the man than we do about ourselves.

On that note, I should also say I that I have indeed matured. Once a snarky Hogan skeptic, I’m drifting toward the status of contented agnostic. I’m comfortable not knowing. If I’d really cared about a resolution, I would have poured my energies into the only project that could ever provide it. I would have got with Hayes and built a time machine.

Zipping through the decades, we could have settled matters once and for all, and then started bickering over Louise Suggs.

Josh Sens welcomes your feedback at josh.sens@golf.com.