Things can go awry quickly under pressure, as seen at this week’s Ryder Cup.

Golf Channel

Welcome to Play Smart, a game-improvement column that drops every Monday, Wednesday and Friday from Game Improvement Editor Luke Kerr-Dineen to help you play smarter, better golf.

HAVEN, Wis. — The task of getting the 2021 Ryder Cup underway fell to Sergio Garcia, a golfer who befits such a task. That may be putting it mildly: The 41-year-old Spaniard has won the same number of points himself as the entire 2021 U.S. Team combined. He’s seen it, done it, and succeeded at it all.

And so, one of the best ball-strikers in modern history set up over his ball, envisioned a little fade sliding down the fairway — and yanked his ball into the left fescue.

A mere 10 minutes later, it was the U.S. team’s premier ball-striker’s turn to repeat the drill. Collin Morikawa, the phenom whose consistent fade has already become the stuff of legend, sent his drive on the first sailing into the left cabbage.

World No. 1 Jon Rahm didn’t take long to get in on the action. On the tight par-4 4th hole, Rahm’s drive left Sergio in a left fairway bunker — a few yards left of where JT’s fade-that-didn’t-fade left his partner, Jordan Spieth.

Faced with the prospect of sending his ball into Lake Michigan, power-fader Dustin Johnson smashed a meaty pull left so far left of the 8th fairway that Morikawa had 245 yards for his next shot into the 283-yard hole.

DJ’s drive on 8 turned the par-4 into a three-shot hole

The vast majority of golfers at the highest level — and, indeed, at the 2021 Ryder Cup — prefer a left-to-right fade as their stock shot. At least 13 of the first 16 players in the morning session, by my count.

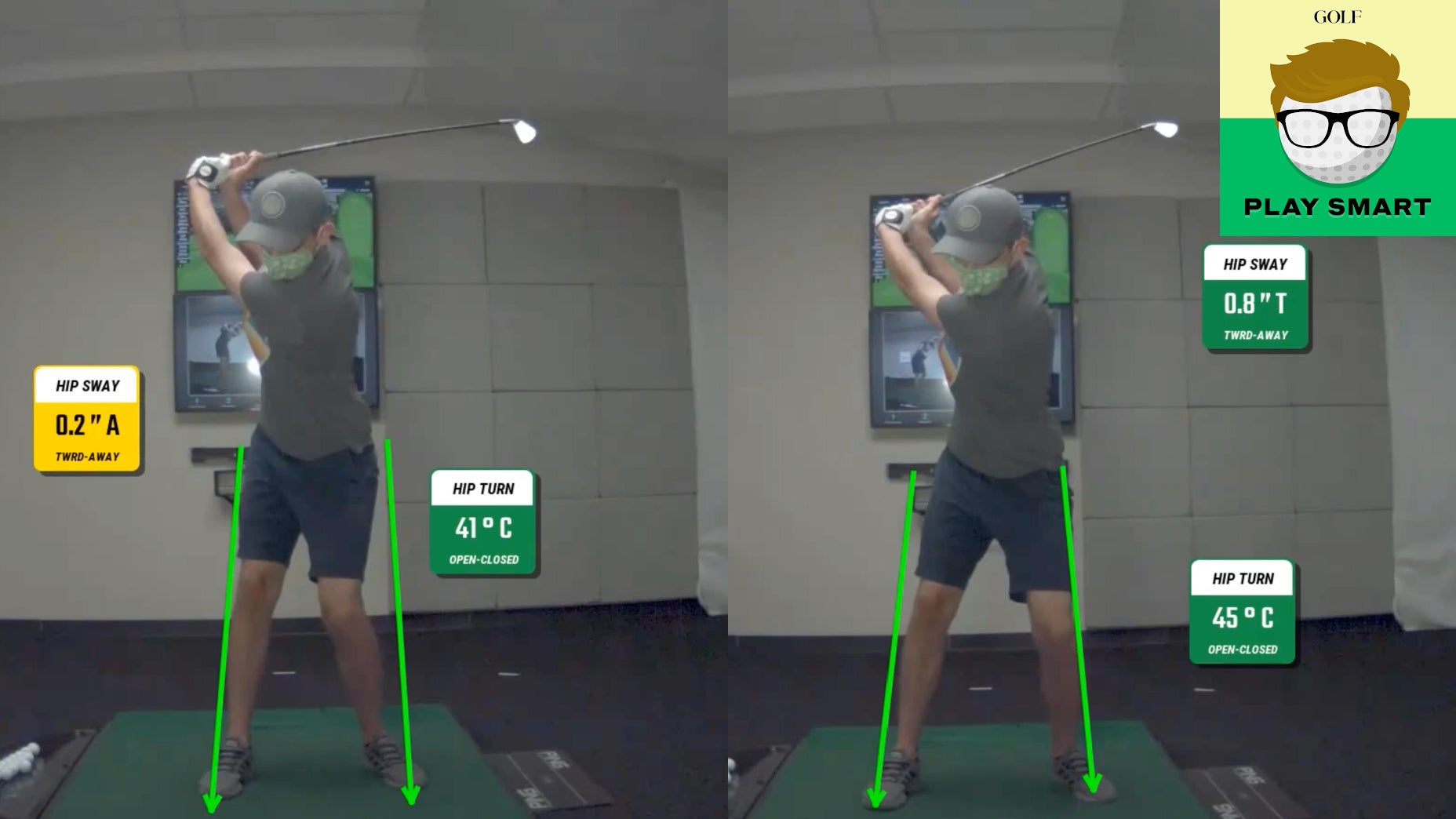

Their logic is that it’s more dependable, which is undeniable: When golfers hit fades, it’s because they limit the release of their hands through impact. This has the effect of keeping the clubface more open at impact, usually on a swing path that moves more down towards the ground and left.

That combination puts more backspin on the ball, which creates a larger margin for error. Rather than mishits that dive uncontrollably low and left, all that extra spin sends the ball softly to the right. Not always perfect, but almost always playable.

But the thing is, humans aren’t hardwired to be golfers. Nervousness is your body’s way of sensing danger, and it responds by going into survival mode. Your heart races and your adrenaline production increases, which makes your brain more alert and muscles more activated. There’s a threat near, so your body enters into overdrive, rapidly rearranging the tools humans need as it enters fight or flight mode.

All of our market picks are independently selected and curated by the editorial team. If you buy a linked product, GOLF.COM may earn a fee. Pricing may vary.

Try OptiMotion at a GolfTec near you

Fill out this form to book a swing evaluation or club fitting and begin your journey to better golf.

Except the Ryder Cup is not an existential threat to your life. It’s a golf shot. A high stakes one, but a golf shot nonetheless. But your body doesn’t know that. So, when even the best players on the planet send their club into the downswing, their ordinarily quiet hands become less so. Juiced with a homemade accelerant, their hands, wrists and fingers become ever-so-slightly more active. The clubface closes down, and sends the ball left. A reliable fade, traded for an unexpected double-cross.

It’s one of the subtle beauties of the Ryder Cup, seeing all the little ways players are pushed outside of their comfort zone.

“There’s nothing like it,” Paul Casey says. “There is no situation in the game where you will have that much pressure on you.”

There’s no preparing for it. And stewing within the cauldron of Ryder Cup pressure, even your most trusted tools aren’t ones you can depend on.