Talor Gooch and Hudson Swafford are looking to join the FedEx Cup playoffs via a temporary restraining order.

Getty Images

When being sued, the defendant would normally have plenty of time to respond to complaints — as much as 21 days, to be precise. But in the case of ‘Mickelson et al vs. PGA Tour’ the PGA Tour didn’t have quite as much time.

Included within the LIV players’ lawsuit was a request for a temporary restraining order to allow Talor Gooch, Hudson Swafford and Matt Jones to play in this week’s FedEx St. Jude Championship, the first leg of the FedEx Cup Playoffs. Gooch, Swafford and Jones each technically earned enough FedEx Cup points to have qualified for the Playoffs, but have each been suspended by the Tour this summer for playing in LIV Golf events. With the tournament starting Thursday, this little corner of the lawsuit needed to be solved ASAP, which means the Tour needed to respond quickly — and it did.

What arrived Monday was a thorough critique of many initial complaints in the lawsuit, particularly pointed at those three golfers trying to earn their way back into the field. Below are eight initial findings worth paying attention to as the court hearing looms Tuesday.

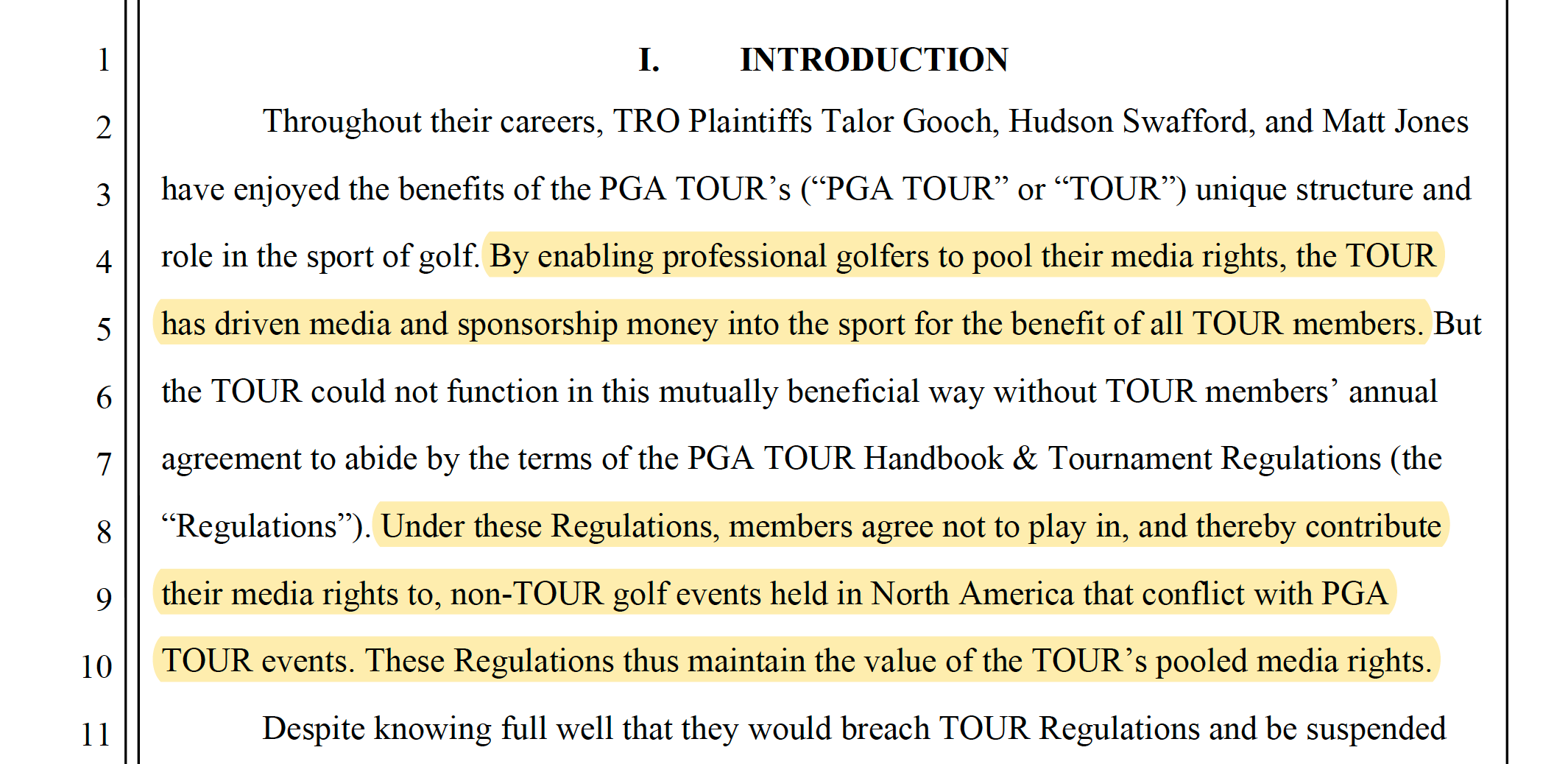

1. Media rights and collective pooling

If there’s one thing in particular this saga has revolved around from start to, well, now, it’s the PGA Tour’s media rights. Each year, the Tour has its members sign on to pool their media rights, believing that as a sum they can be greater than their individual parts. The pool of those rights is used to create massive television rights deals — the most recent of which began in 2022 — advertising, sponsorship value, etc. Protecting the pool of those media rights, the Tour is arguing, is vital to its business, so it is not keen on allowing members to just play anywhere at anytime.

The trouble comes into play when players want to play elsewhere during the week in which a Tour event is being staged, particularly in North America. When Tour members request to do so, the Tour argues they are theoretically devaluing the rights they’ve signed away under PGA Tour regulations. Phil Mickelson, as we have come to understand, disagrees with this system wholeheartedly. It led to his infamous “obnoxious greed” comments from January. This week’s hearing may be focused on plaintiffs earning their way back into the FedEx Cup, but at some point that still evolves from their decisions to play without a media rights release from the Tour.

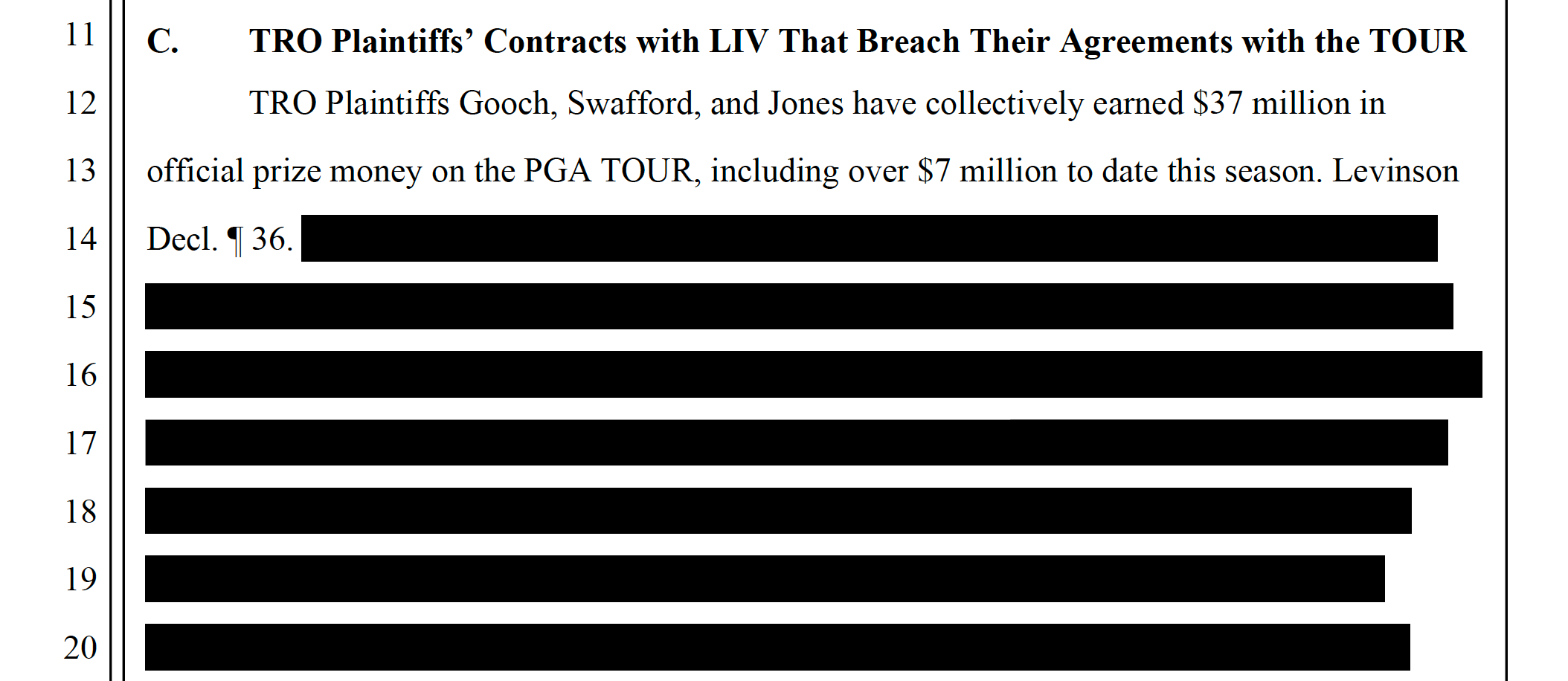

2. Confidentiality agreements

For the first time in this young lawsuit’s life, we had a motion to file documents under a seal. In other words: to keep specific things confidential. In this case, it’s contract-specific details about how much money LIV golfers signed on for with their upfront agreements with the upstart league.

According to the declaration from Elliot Peters, one of the lead attorneys representing the PGA Tour, those documents were shared with the PGA Tour for the first time on August 5. That’s just last week, two days after the lawsuit was initially filed. At the request of the plaintiffs, the PGA Tour “acquiesced” to allow the “run-of-the-mill agreements” to remain confidential. That being said, the Tour’s legal response noted that it “is contemporaneously filing an Administrative Motion to Consider Whether Another Party’s Material Should be Sealed.” In other words, those confidential markings you see above could be whisked away at a later day. Included within those contemporaneous motions is LIV Golf’s current rules and regulations of its Invitation Series.

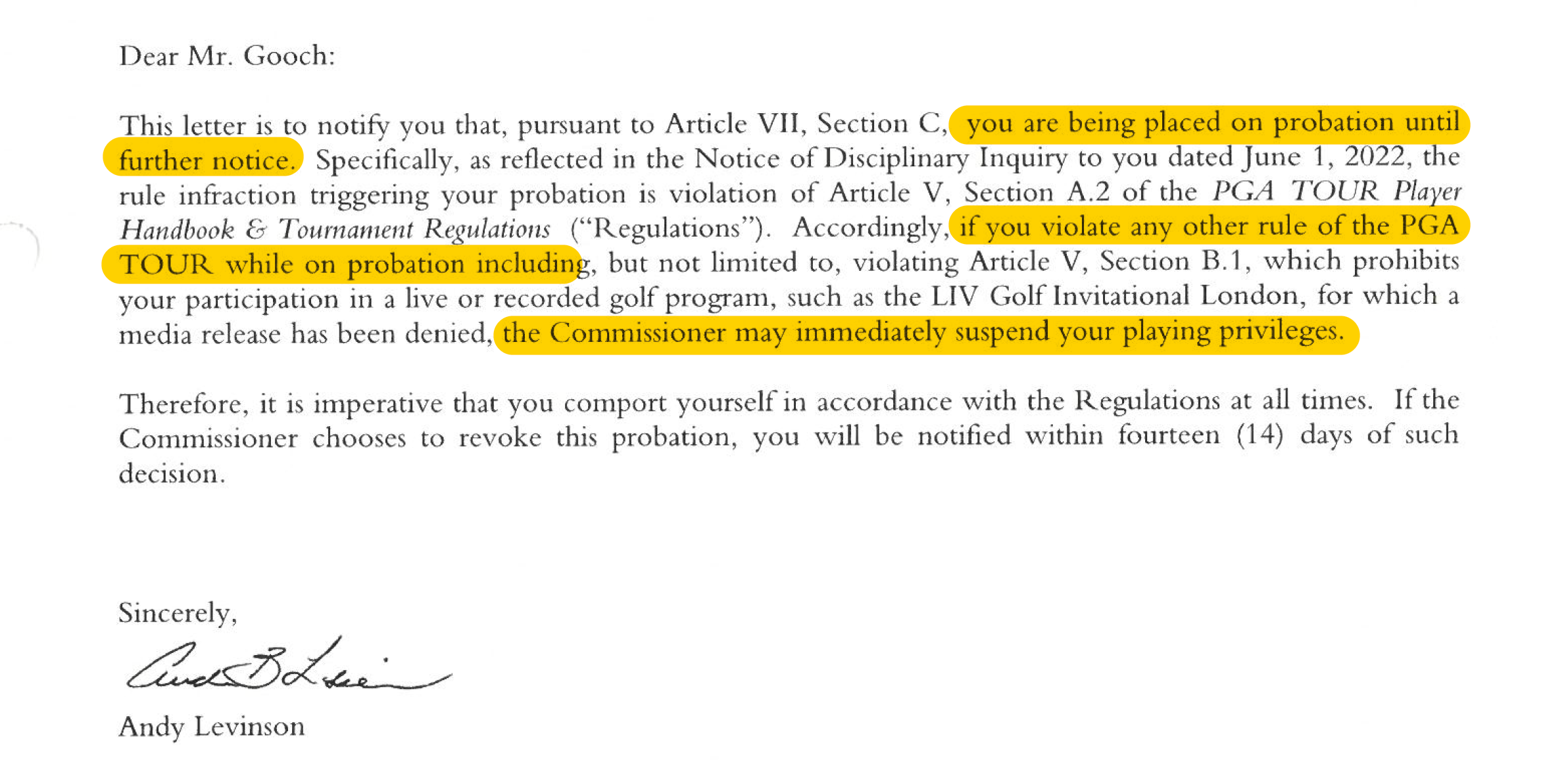

3. The players knew a suspension was coming

One of the biggest moments this summer came when players teed off at the Centurion Club in the first LIV Golf event on June 9 and Tour commissioner Jay Monahan promptly suspended them. That afternoon, when LIV golfers finished their round, reporters asked if they were surprised. Regardless of what they said at the time, they really couldn’t have been.

According to the Tour’s various exhibits filed Monday, Gooch, Swafford and Jones all received multiple formal warnings against taking part in the LIV Golf London event. First, on June 3, three days after the field was announced, a Notice of Disciplinary Inquiry to Swafford and Jones. Then the same to Gooch on June 5. To paraphrase it, We denied your release to compete in an event, per our regulations, why are you still in the field in England? According to emails, the players were granted 48 hours to confirm that they were not going to take part. When those 48 hours passed, they were sent another email clarifying they were being “put on probation, until further notice.” In that same notice was the clause, “the Commissioner may immediately suspend your playing privileges.” Then, on June 9, the suspension notice. The calendar stacks up.

4. How much is this an “emergency”?

The temporary restraining order that Gooch, Jones and Swafford seek was filed on August 3, exactly eight days before the first round of the FedEx Cup Playoffs were set to begin. But through the various suspensions that LIV golfers received in response to them playing in subsequent events, the PGA Tour is arguing that Gooch, Jones and Swafford have known they would be barred from competing in the Playoffs for months. In other words, it didn’t dawn on them last week. So why file the request now?

According to the declaration from Tour SVP Andy Levinson, Gooch applied to play the event on April 12. He was withdrawn from the field on July 12. According to the same declaration, Jones applied to play the event on June 21 and was also withdrawn on July 12. Swafford, on the other hand, repeatedly applied to the field despite the Tour repeatedly withdrawing him. According to Levinson, Swafford has tried to commit to the event as many as five times, each time being withdrawn by the Tour. Does this petty sequence matter? It might in regards to the temporary restraining order, as it signifies that these players have known about this consequence of their actions for months. Could it be deemed an emergency issue if it is just now being settled in court, despite all that history and repetitive communication of sanctions from the Tour? We’ll save that decision for the judge.

5. The Tour has receipts, too

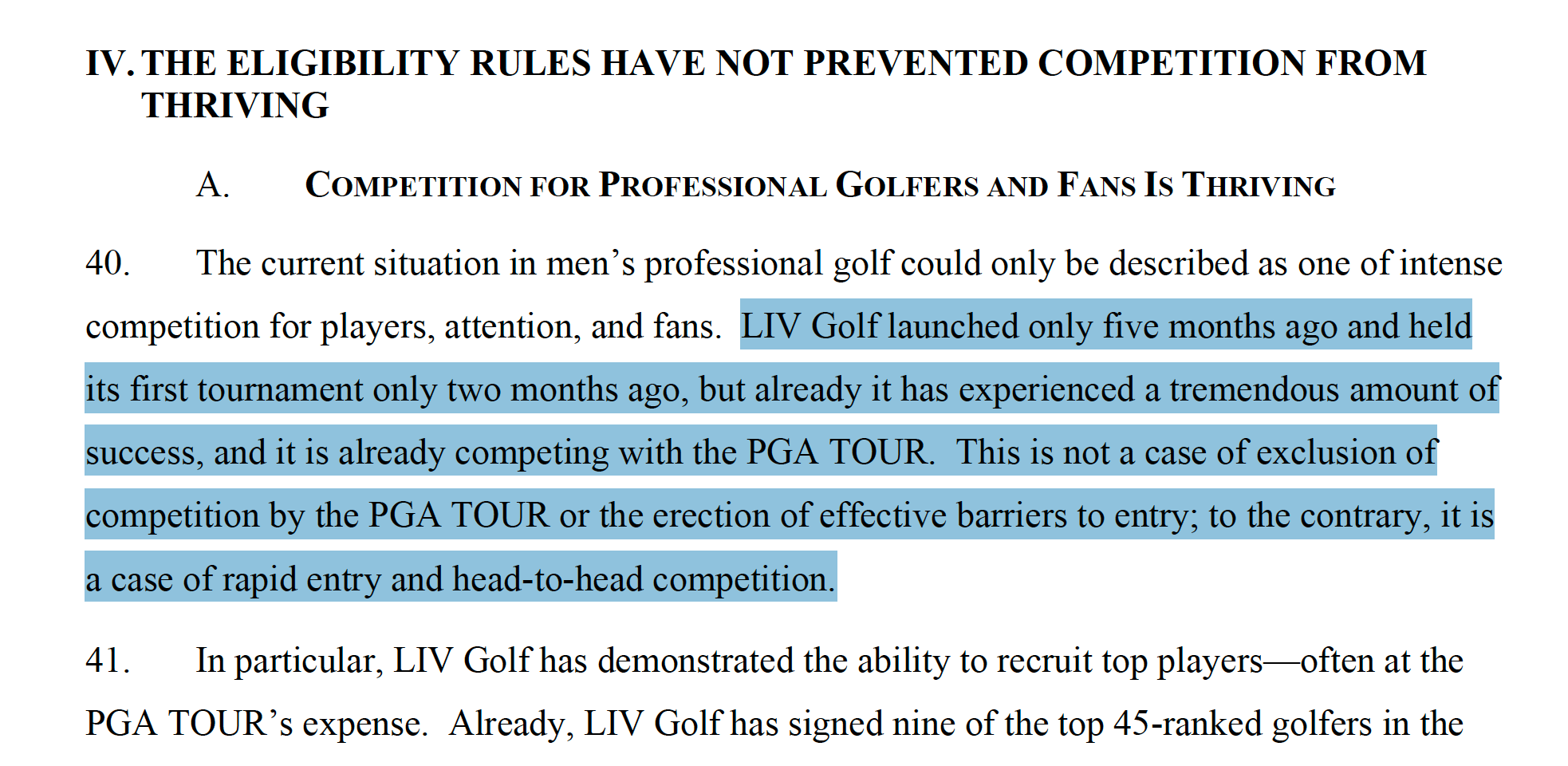

Part of the early acts of litigation like this is a broad, sweeping list of complaints, like we saw from the plaintiffs last week, followed by responses to those exact complaints. It could be acknowledging omissions, correcting perceived falsehoods, etc. Monday served as the PGA Tour’s opportunity to respond, and it did.

The Tour submitted an extensive exhibit of facts and information from the plaintiffs’ complaint that the Tour believed to be inaccurate and/or false and misleading. Seemingly the most important example involves the DP World Tour. One of the main arguments that the lawsuit alleges is a “group boycott” formed by the PGA Tour, inclusive of the DP World Tour and the governing bodies that organize the major championships. According to the Tour’s explanation, the plaintiffs “selectively cite news reports, third-party statements, and press statements to attempt to suggest collusion.” That is accurate. The Tour just thinks it’s purposefully selective and noted the initial claims weren’t as compelling once rebutted with direct quotes from the DP World Tour CEO Keith Pelley.

6. Anticompetitive? The Tour sees the exact opposite.

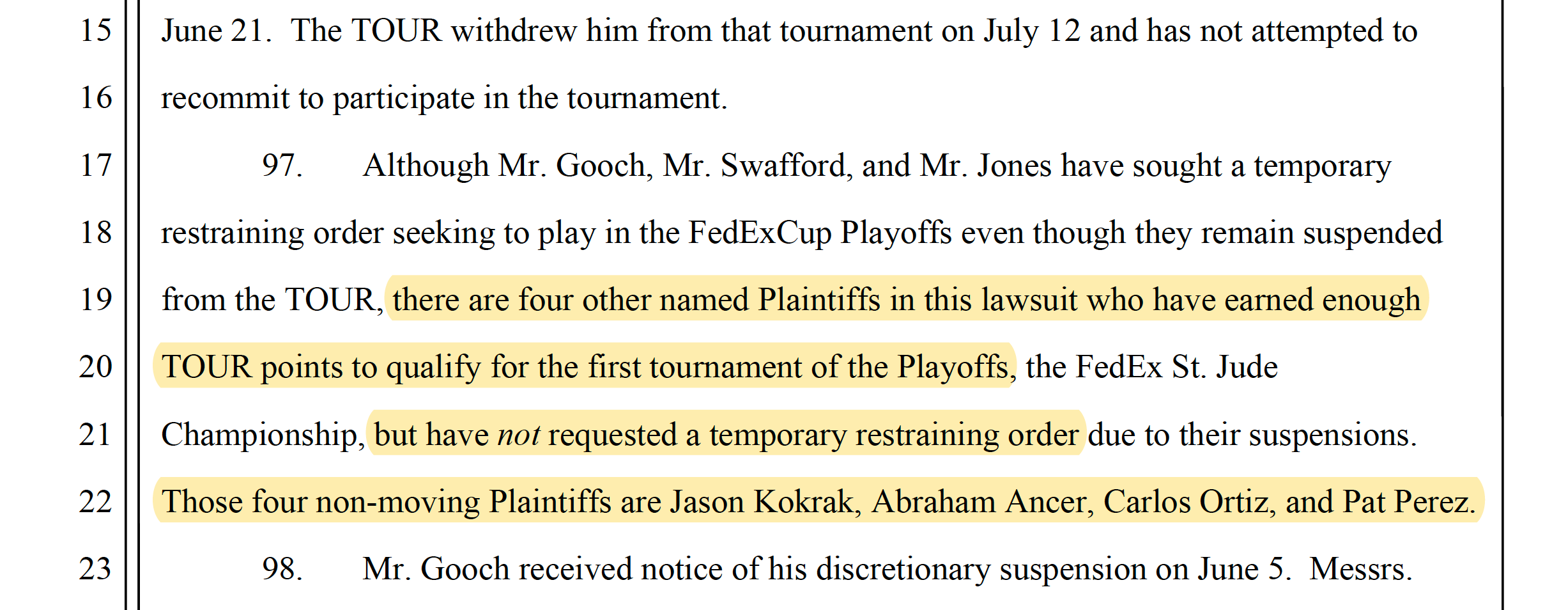

One particularly interesting battle of semantics is due to play out in the coming months as lawyers, plaintiffs, defendants and judges decide what a golf monopoly actually looks like. Because at one point, it could take the exact form of the current PGA Tour as we know it. And that would imply that there is no reasonable room for competition in the industry. On the other hand, the inspired success of LIV Golf, which the Tour has long wanted to thwart, could be a point the Tour would use to argue that true competition is taking place.

In the filings shared Monday was an expert declaration from Mark Israel, an economic consultant who works on antitrust business. Among Israel’s conclusions was the PGA Tour is indeed seeing great competition in the space from LIV Golf, inspiring it to react in a competitive way; not the anticompetitive way that the plaintiffs are asserting. So, what is happening? Certainly the LIV golfers have alleged some seriously questionable behavior at the PGA Tour. But at the same time the Tour has lofted up shadow praise for LIV Golf and its success in its young, five-month public life. It all feels extremely performative. Welcome to the court room!

7. Why these three pros?

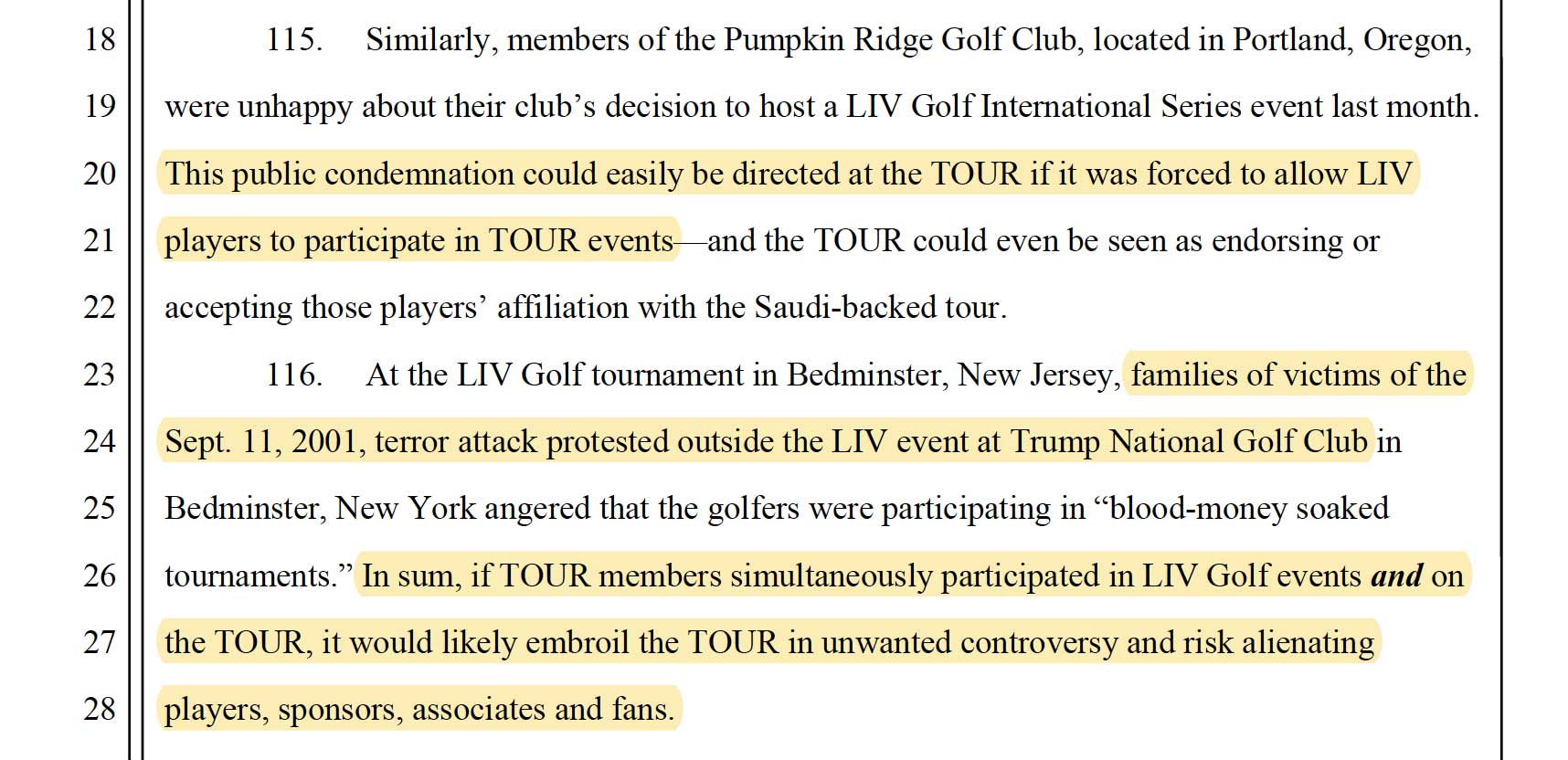

The Tour would like to know. There are many ex-PGA Tour players who have committed to LIV Golf at this point, but only 11 of them are named in the lawsuit. And even fewer are included in the motion for a temporary restraining order.

Levinson’s declaration was keen to point out that four other LIV golfers named in the lawsuit are not looking to play in the FedEx Cup via a temporary restraining order. Why is that? Trust that Jason Kokrak, Abraham Ancer, Carlos Ortiz and Pat Perez — all named by Levinson — will share a similar answer when asked about it at the next LIV Golf event, in Boston in September. Until then, we wait.

8. ‘If this, then what?’ clauses

At the tail end of Tour SVP Andy Levinson’s declaration came an important section about reputation damage. On paper, we are watching a lawsuit play out between a 501c(6) non-profit organization and players from a start-up league bankrolled by the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia. The Tour wants to enact on that context.

Levinson was plenty happy to invoke the term “sportswashing,” which many critics of the LIV Golf series have used to explain Saudi Arabia’s financial investment in the plaintiffs. The Tour, Levinson declares, would not want to associate with the same implications that LIV Golf has been associated with. Levinson states that allowing the temporary restraining order and allowing LIV golfers to compete in Tour events could incur some of the same reputational damage for the Tour that the plaintiffs have received. Saudi Arabia’s human rights record and the country’s direct connection to the 9/11 terrorist attack have clouded LIV Golf events all summer. The PGA Tour wants none of those associations.

Are Levinson’s ‘If this, then what?’ assertions fair? Perhaps. Are they relevant? We’ll see what the judge decides.